Playing God in Gynecology: Fertility and White Supremacy

By Amelie Horn

- Several bottles of DES pills.

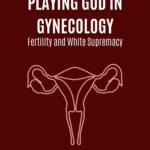

- DES advisement promising healthy babies.

TRANSCRIPT:

Intro music and background noise of driving in the rain

Hello, I’m Amelie Horn and you’re listening to Playing God in Gynecology: Fertility and White Supremacy.

When I was 16, I found myself in the gynecologist’s office for the first time where I was told I had a malformed hymen, and bad endometriosis. I couldn’t wear tampons; I missed school from pain so debilitating I could barely walk some days. That summer I had my hymen surgically removed and an IUD placed.

No one told me that it could have something to do with an artificial hormone I barely knew the name of. No one told me that while the studies on DES, also called Diethyl Stilbestrol had stopped at my mother’s generation, the pain could continue into mine.

My great grandmother took DES in the late 1940s in an effort to carry her first and only biological child to term, my grandmother. DES was an early synthetic version of estrogen advertised to prevent miscarriage and promising healthy babies to those privileged enough to afford it. She gave birth to a seemingly healthy baby girl as advertised by the drug company.

This brings us to an obvious question: What is DES?

DES was a drug given to prevent miscarriage (although according to DES Action Network, an advocacy group for victims of DES exposure, there is no evidence it actually did so). What it did do was create a generation of children born with a myriad of birth defects and high cancer risks.

Children of DES have significantly higher rates of a rare cancer called Clear Cell Adenocarcinoma (CCA) of the Vagina and Cervix, malformations of the uterus and vagina (like tipped or heart shaped uteruses), endometriosis, ectopic pregnancy (or pregnancy outside the uterus), stillbirth, miscarriage, preterm labor, uterine fibroids, early menopause, para ovarian cysts, adenosis, hypospadia, undescended testicals and more. There’s a whole laundry list of effects

In summation DES was poorly tested and dangerous with effects cascading down generations, but at the time mothers took it, it was a huge privilege.

While white upper middle class and wealthy women like my grandmother were test subjects for experimental fertility boosters, women of color especially Black women, Indigenous women and Puerto Rican women were used as birth control guinea pigs without their consent.

For example, in 1956 biological researchers Gregory Pincus and John Rock decided that Puerto Rico was an ideal location for human trials of the birth control pills because they considered Puerto Rican women to be uneducated and in need of birth control due to poverty. The idea being that if poor uneducated women of color could take the pill, anyone could. They advertised it as %100 effective, and dismissed side effects like stroke, nausea, dizziness, headaches, stomach pain and vomiting. It lowered the birth rate, and that was the goal. Complications were not a consideration because to Pincus and Rock what mattered was fertility not health of the women involved.

Activist and philosopher Angela Davis summed up this dynamic in her essay Racism, Birth Control and Women’s Rights where she connects the idea of racial suicide, the notion popularized in the early half of the 20th century in which the idea of white women choosing not to have children is seen as a form of racial suicide, to birth control experimentation and sterilization abuse against women of color. She summed the connection up as, “While women of color are urged, at every turn, to become permanently infertile, white women enjoying prosperous economic conditions are urged, by the same forces, to reproduce themselves.”

This idea of white women reproducing no matter the cost is still felt in my family today. My grandmother was born with a tipped uterus, and my mother has what her gynecologist called one of the worst cases of endometriosis and abdominal scarring following a C section that she had ever seen. Both my mother and grandmother are part of an intergenerational study on DES exposure, but I am not. There is no research I can find on my generation, and I don’t know that I’ll ever have closure on this part of my history.

Furthermore, my family story is not unique. In the Smith college archives this story plays out again and again in minutes of DES action meetings, stories of second-generation pregnancy lost tucked neatly into survey results, and statistics on cancer typed up by women who refused to be silenced. I’m reaching out to researchers now, and it is a project that would span years and cost a lot of money, but I take tremendous courage from the archives and seeing the steps the women who walked this path before me took. I’m sure they felt alone and helpless in this too, but they found community and answers. So will I. My family and others born into the intersection of fertility, experimentation and white supremacy deserve research and solutions. From birth control to fertility experimentation (both of which continue today) we need to push for reproductive justice, reproductive health care and an end to the role privilege and white supremacy play in gynecology today.

Sources

DES Action USA records, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Mass.

https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/146810 Accessed October 31, 2022.

Davis, Angela. “Racism, birth control and reproductive rights.” Feminist postcolonial theory: A reader (2003): 353-367.

“CAMPAIGN TO RESTORE FUNDING FOR THE DES FOLLOW-UP STUDY.” Des Action USA, DES Action USA, https://desaction.org/.

“The Puerto Rico Pill Trials.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/pill-puerto-rico-pill-trials/.