Julia Doerschler

This podcast discusses the history of queer parents from the 1950s to the present, as well as methods queer people use to become parents. This includes persecution of queer parents and activist movements.

Transcript- Queer Parents: History and Parenthood

The choice whether or not to raise children is a choice everybody should be able to make. However, the choice is much harder for queer and trans couples. The biological ability that cishetero couples often have to give birth and society’s comfort with adoption within cishetero relationships, allow for these couples to have much easier paths to wanted parenthood.

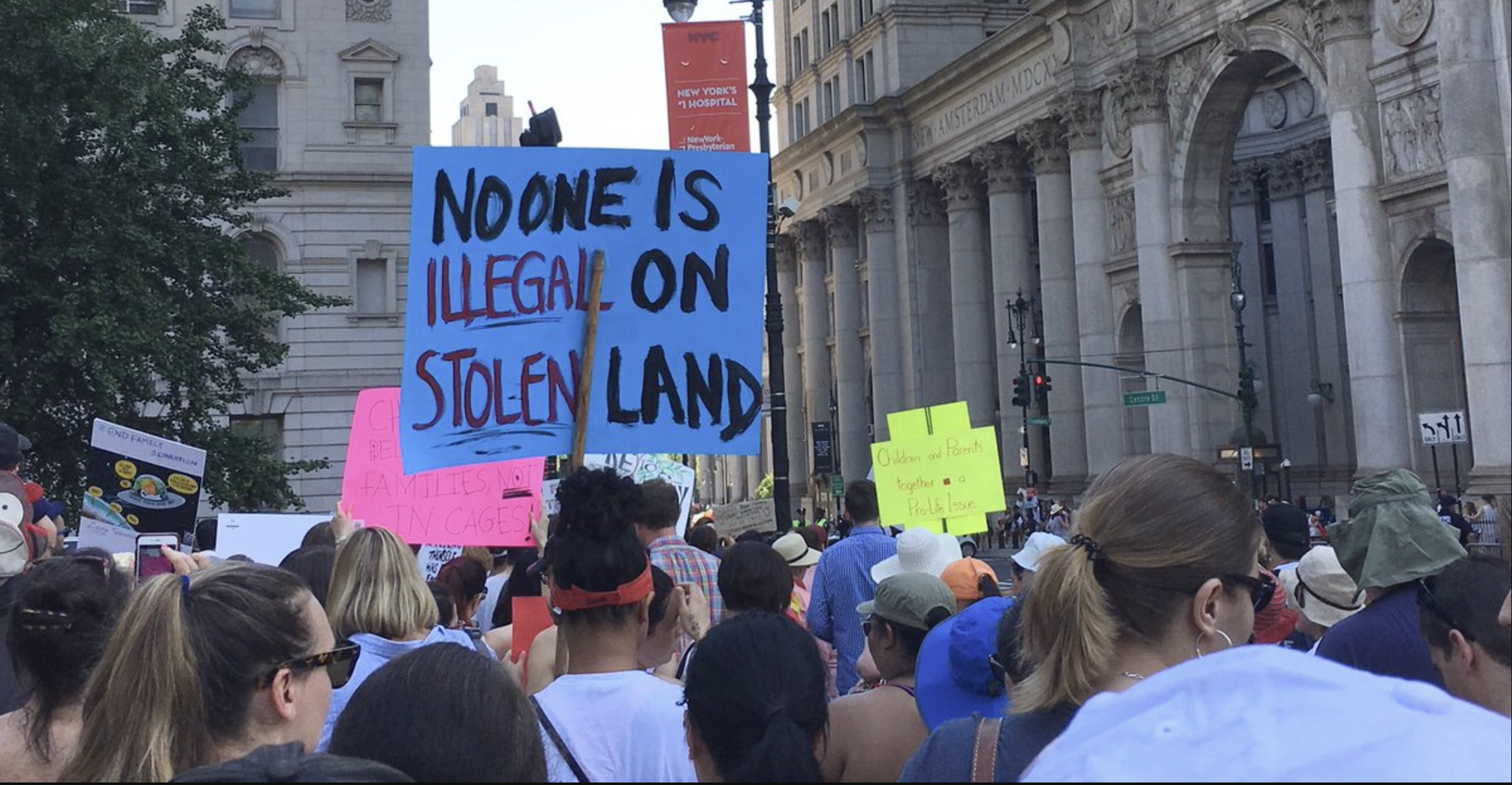

Before I continue I want to say that in this podcast I am going to discuss the right to have a child, specifically in queer relationships. However, I want to point out that choosing to be a parent is also made inaccessible to other marginalized groups such as people of color, immigrants, and lower class folks due to forced sterilization, deportation, unsafe environments, financial struggles, etc..

Following World War II, many people began to come to terms with their homosexuality as gay and lesbian groups formed. However, gay men and lesbians became targets for persecution and antigay campaigns. As a result, a fear of homosexuality spread to the public, which led to a concern for the safety of children around gay men and lesbians. In the 1950s, the fear spread amongst gay and lesbian parents who were concerned that their children would be damaged or turn out to be homosexual as well. Although these fears were proven false by childhood development specialists, gay and lesbian parents continued to be targeted. The loss of custody of children and persecution was a continuous problem for queer parents, resulting in many hiding their true sexuality.

Lesbians were raising children more frequently than gay men during the 1950s and 1960s. Due to becoming pregnant from either brief affairs with men leaving the women pregnant, or pregnancy in marriage with men, later resulting in divorce, queer women were able to raise a child without a man. Because of the “nuclear family” standard of men earning the salary for a family, lesbians and single mothers often faced financial difficulties. In 1956, lesbian activists Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon created groups for lesbian mothers through their organization Daughters of Bilitis, a lesbian activist group involved with civil rights and other social movements. During this time, these groups were the first public acknowledgement of lesbian mothers. In 1971, Martin and Lyon created the Lesbian Mothers Union. The group raised money for lesbian mothers who were at risk for losing custody of their children.

Many gay men who had children from previous relationships struggled with keeping contact with their children. During custody battles, two men looking for custody of a child were much more suspicious than two women, which was much more acceptable in society. Because of societal norms, gay men were specifically pressured to marry women and have children with them. This is the most common way of how gay men and lesbians were able to become parents during the 50s and 60s.

From the 1970s on, queer couples started to become more open about their sexualities, however, more recognition of gay men and lesbians also led to more backlash. Through the early 1980s, queer parents continued to lose their children through custody battles. Some were banned from being with their child and their same-sex partner at the same time, and some even lost full contact with their children for years. The loss of children led to an uproar in queer activist groups. The Lesbian Mothers Union as well as other lesbian mothers and gay fathers organizations were more active than ever. In 1985, a clear change was being made due to the activist groups. In states with larger queer populations, queer parents were more frequently gaining custody of their children.

In the 80s and 90s, queer couples seeking parenthood without heterosexual encounters or relationships became more frequent. Through methods such as sperm donor insemination, surrogacy, and adoption, queer couples were able to start families. Even though queer couples had these new freedoms, many still faced discrimination when trying for a family. For lesbian couples and single women looking for sperm donor insemination, sperm banks would often deny them. Adoption agencies would also often deny queer couples from adopting or fostering a child.

Activism surrounding queer parenting began to change in the 1990s. Activist groups began to include transgender and bisexual identifying parents into their work and organizations. These new groups not only advocated for custody, but also included topics such as adoption, insemination, surrogacy, raising children, and support for queer parents.

Within the past 30 years, queer couples have continued to start families. Representation of families with queer parents in the media has increased, allowing for awareness to be spread about multiple types of family structures. But just like in years past, more backlash has occurred. Legal battles continued to be fought, including a Florida Supreme Court Case that former President Bush publicly supported. Despite the backlash, queer parents have been able to continue to have children and gain medical and legal rights.

So, how do queer people actually have children? Some are still having children through cishetero couples, but there are countless other ways. For trans relationships, where either one or both are trans, they are sometimes able to have children that are biologically related to both parents. For example, a trans man becoming pregnant from a cisgender man or transgender woman. LGBTQ+ identifying folks, also often adopt children. Adoption is a method of becoming a parent that many people use, including queer couples, cishetero couples, and single parents. Adoption can be a way for two people to have a child without either partner giving birth. For some couples, when one partner gives birth to a child, for example, through IVF or a child from a previous relationship, the other partner may adopt the child so they both have legal guardianship.

Medical methods include sperm donor insemination, in vitro fertilization known at IVF, and surrogacy. Sperm donor insemination is a method used for people who were born female. This method works by injecting semen from a sperm donor directly into the vagina during ovulation. This method is often successful, depending upon the person’s health and age. IVF is a method similar to insemination, but the eggs are fertilized in a lab first, instead of being directly injected. Reciprocal IVF is a type of IVF that allows for both partners in a cis-lesbian couple to participate in pregnancy. Just like conventional IVF, eggs are retrieved from one partner to be fertilized from sperm from either an anonymous donor, friend, or family member. Once both partners menstrual cycles synchronize from medication, fertilization and implantation can occur. Healthy embryos will then be implanted into the other partner, in hopes of pregnancy. Surrogacy is often used for gay men, but can be used for multiple types of queer relationships. Surrogacy also often uses IVF. One partner from a couple will use their sperm to fertilize donated eggs in a lab setting. The surrogate will then carry the embryo, but after the surrogate gives birth, they will give the child to the couple looking to become parents.

I have discussed the history of queer parents and some common ways queer folks are able to become parents. The access queer folks have to become a parent is still a pressing reproductive justice issue that many are still fighting for. Although queer rights, especially trans rights have been targeted recently, representation, organizations, and queer advocacy has made the right to become a parent easier and more accepted in society.

References

Editor. “Donor Insemination.” American Pregnancy Association, October 6, 2022. https://americanpregnancy.org/getting-pregnant/donor-insemination/.

Orleck, A., “Lesbian Lives, Lesbian Rights, Lesbian Feminism.” Rethinking American Women’s Activism, edited by Thompson H. A.. New York, New York: Routledge, 2022.

“Reciprocal IVF: LGTBQ Families: Reproductive Science Center NJ.” Reproductive Science Center of New Jersey. Accessed December 3, 2025. https://www.fertilitynj.com/fertility-treatment/reciprocal-ivf.

Rivers, Daniel Winunwe. “Epilogue: Lesbian Mothers, Gay Fathers, and Their Children after Lawrence v. Texas.” In Radical Relations: Lesbian Mothers, Gay Fathers, and Their Children in the United States since World War II, 207–16. University of North Carolina Press, 2013. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469607191_rivers.12.

Rivers, Daniel Winunwe. “Lesbian Mother Activist Organizations, 1971–1980.” In Radical Relations: Lesbian Mothers, Gay Fathers, and Their Children in the United States since World War II, 80–110. University of North Carolina Press, 2013. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469607191_rivers.8.

Rivers, Daniel Winunwe. “The Seeds of Change: Forging Lesbian and Gay Families, 1950–1969.” In Radical Relations: Lesbian Mothers, Gay Fathers, and Their Children in the United States since World War II, 32–52. University of North Carolina Press, 2013. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469607191_rivers.6.

“Surrogacy for LGBTQ+ Parents | Circle Surrogacy.” Circle Surrogacy. Accessed December 3, 2025. https://www.circlesurrogacy.com/intended-parents/who-we-help/lgbtq-parents.