Maddie McAllister ’26

Reproductive Injustice Through a Queer Lens tells the story of the brave lesbian mothers of the late twentieth century who organized and fought for the right to raise their own children and views their efforts through the lens of the reproductive justice framework.

Transcript – Reproductive Justice Through a Queer Lens

(0:11) Hi! I’m Maddie McAllister and you’re listening to my contribution to the Listening for Reproductive Justice Podcast Anthology!

(0:18) When I initially heard the term “reproductive justice,” the first thing that came to my mind was the issue of abortion. It might be a product of the terrifying political climate we’re all currently living through with the overturning of Roe v. Wade, but before coming to Smith, everything I knew about reproductive rights revolved around access to abortion and birth control.

(0:35) As an aromantic asexual woman who doesn’t plan on ever becoming pregnant, June’s Dobbs v. Jackson decision scared me, sure, but it didn’t galvanize me the way it did some of my peers. The issue was just so disconnected from the life I was living that I didn’t quite know what to do with it. When I stumbled across some lesbian custody paperwork in the Sophia Smith Collection, I knew immediately what I wanted to focus on with this project. So without further ado, I present: Reproductive Injustice Through a Queer Lens: A Brief History of the Lesbian Custody Issue

(1:04) Most people don’t think of queer women when they think about reproductive justice or reproductive rights, but the 1970s brought lesbian mothers–something of an oxymoron at the time–to center stage. As homosexuality gained attention at the more mainstream level, more and more lesbian women in heterosexual relationships gained the courage to come out and divorce their husbands. While homosexuality was becoming more socially acceptable with the beginnings of the gay liberation movement and the rise of lesbian feminism, it was still classified as a mental disorder by the American Psychiatric Association, and these lesbian mothers often faced custody battles with their ex-husbands or other family members who thought that they were unfit to raise their own children.

(1:44) In their book, Reproductive Justice: An Introduction, Loretta Ross and Rickie Solinger lay out the three core principles of the reproductive justice framework: “(1) the right not to have a child; (2) the right to have a child; and (3) the right to parent children in safe and healthy environments.” Later on, a fourth core idea was added: that “individuals have the human right to disassociate sex from reproduction, and healthy sexuality and pleasure are essential components to whole and full human life,” to quote the presentation Professor Ross gave our class on reproductive futurism. The lesbian custody crisis of the 1970s and 80s hits on the third and fourth tenets of the framework, the right to parent one’s own child or children and the right to sexual pleasure not contingent on the goal of reproduction. Many rulings in lesbian custody cases were in direct violation of these tenets and of the fundamental human right to sexual autonomy.

(2:36) The general rule of thumb in custody cases at the time was “the best interest of the child,” a deliberately vague phrase that left the judge in any given case a huge amount of power. Most treated it as a given that being raised by a lesbian was not “in the best interest” of any child. The rationale for this usually hinged on ridiculous but widespread ideas, like the fear that children of lesbian mothers would face stigma from society that could result in psychological damage. Another common fear was that being raised by gay parents would somehow make a child grow up to be gay. When attacked with any degree of logic, these theories completely fall apart, but these notions were so pervasive that lesbians were losing their children in droves.

(3:14) Even cases that would have been no-brainers if the mothers were heterosexual were being lost by lesbians. For example, in 1975’s Townend v. Townend, custody of Larraine Townend’s children was given to a grandmother who had never volunteered for such a responsibility. The reasoning behind the decision? According to Nan D. Hunter and Nancy D. Polikoff’s “Legal Theory and Litigation Strategy” for “Custody Rights of Lesbian Mothers,” Larraine’s ex-husband had ignored his children for ten months and at one point had attempted suicide in front of them, and of course, Larraine was a lesbian.

(3:45) Addressed in the same document, Marilyn Koop’s younger two children ran away from their father’s house multiple times after she was denied custody, and the court still refused to reconsider their ruling. The prejudice demonstrated in so many of these cases ultimately kept a generation of kids away from their queer parents and traumatized both parties instead of keeping the children safe. In the documentary Mom’s Apple Pie, Melissa Hart, who was taken away from her mother at age nine, says that she will “never forget the trauma” of that day. Barbara Price, also interviewed for the documentary, says that her two year old son was so traumatized by his sudden change in circumstances that he stopped speaking for six months after his mother lost her custody battle.

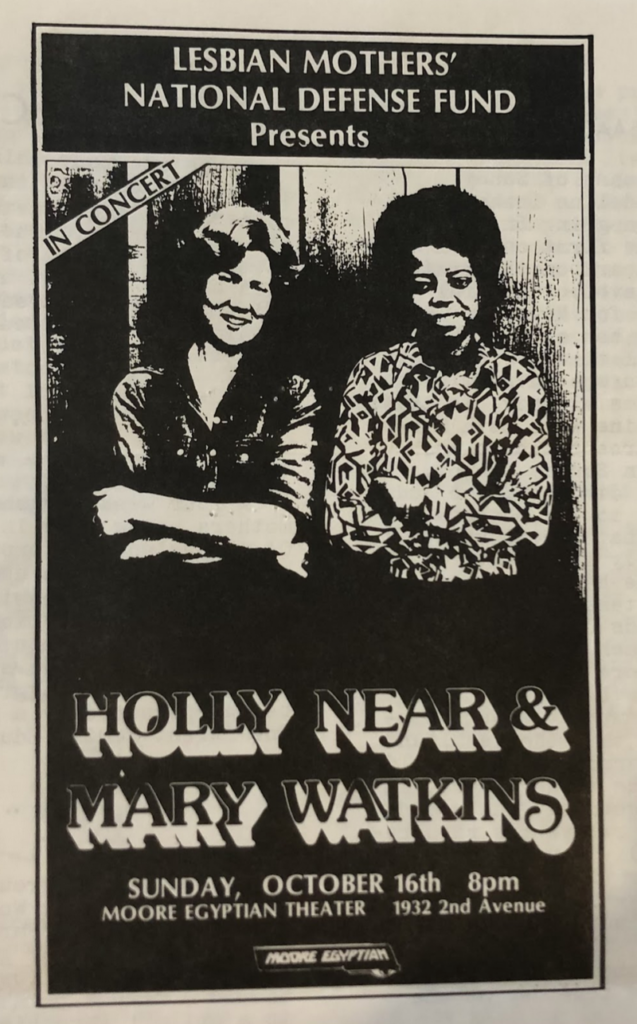

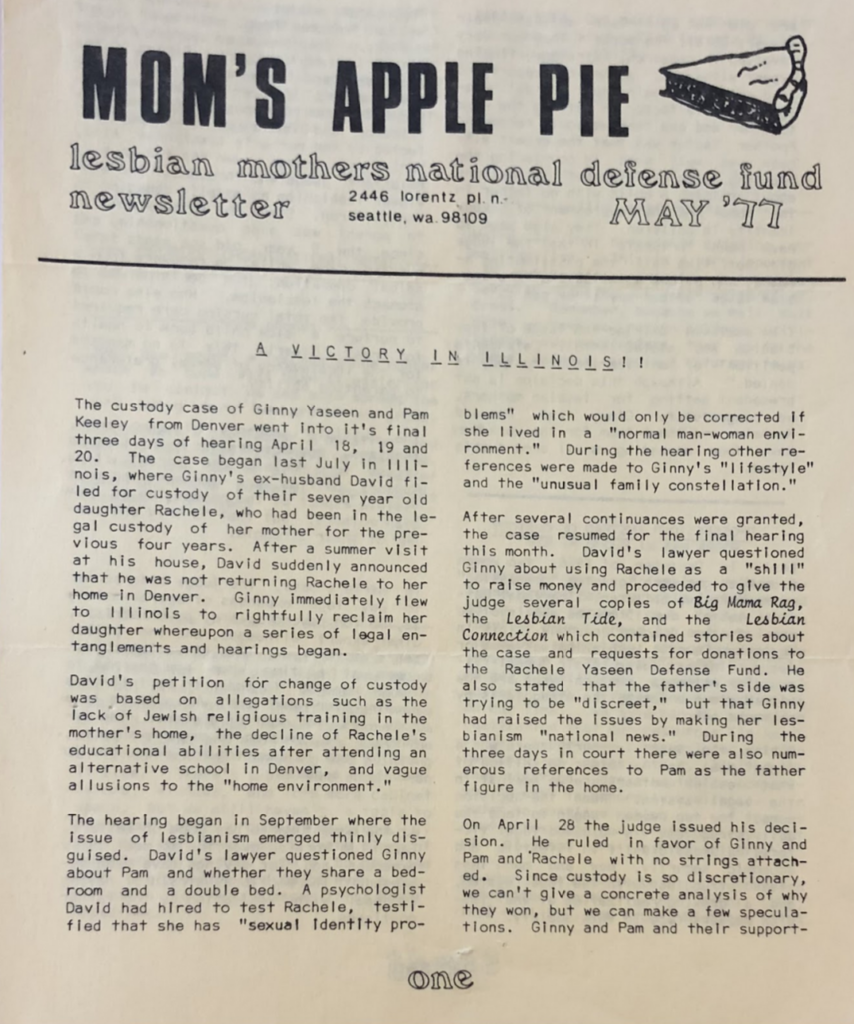

(4:25) But lesbian mothers weren’t about to give up without a fight. Groups like Custody Action for Lesbian Mothers, Dykes and Tykes, and the Lesbian Mothers’ Union formed to call attention to these issues and hopefully make a difference. The Lesbian Mothers’ National Defense Fund was perhaps the most famous of these groups. The Seattle-based organization formed in 1974 and used the resources they had available to them to support lesbian mothers who were going through custody battles. According to the documentary, the average cost of a lesbian custody case was $10,000 at the time, and the LMNDF raised money to help these mothers pay their lawyers and legal fees. Their newsletter, Mom’s Apple Pie, printed ongoing updates on lesbian custody cases, advertised fundraisers like talent shows, movie nights, benefit dances, and concerts, provided information about helpful resources and opportunities for lesbian women, and printed and answered letters from their subscribers. As stated in the documentary, the LMNDF provided assistance to over 400 lesbian mothers from 1974 to 1980.

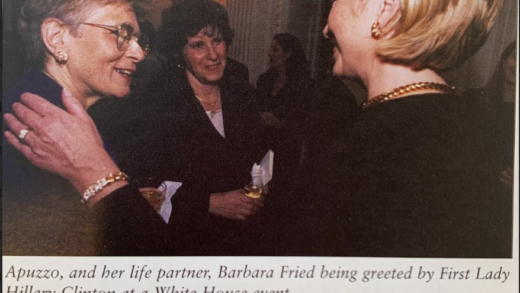

(5:24) As a result of the hard work of organizations like LMNDF and the gradual destigmatization of homosexuality, the tide really started turning for lesbian mothers around 1985, when a lot more women started to win their custody battles and old custody decisions were even overturned in favor of lesbian mothers. The lesbian custody movement of the 1970s and 80s shows us a notable shift from the queer activism of the late 20th century to the more marriage- and family-oriented movement that we see today. These lesbian custody battles were integral in introducing the public at large to the concept of gay parents and families, and this inclusion of queer women in the larger movement for reproductive justice was revolutionary.

(6:03) Today, families with two moms or two dads are commonplace, and in my experience, are rarely treated with any vitriol from other parents or community members. While this could be because I’ve lived my whole life in Massachusetts, the casual attitude I have noticed toward queer families still signifies an enormous shift in the public perception of what a family is as compared to what it was during the 70s and 80s. How did we get here? It’s definitely a multifaceted question, but to quote a motto of the LMNDF, the lesbian mothers of the late twentieth century showed the world once and for all that “raising our children is a right, not a heterosexual privilege” and they helped pave the way for the queer parents and nontraditional families we see so much more often today.

Thanks for listening, and be sure to tune in to some of the other incredible podcasts included in this anthology!

References

- Hunter, Nan D., and Nancy D. Polikoff. “Custody Rights of Lesbian Mothers: Legal Theory and Litigation Strategy,” 1976. Rhonda Copelan Collection, Box 2, Sophia Smith Collection of Women’s History

- Lesbian Mothers’ National Defense Fund. “A Victory in Illinois!” Mom’s Apple Pie, May 1977.

- Lesbian Mothers’ National Defense Fund. Mom’s Apple Pie, November 1977.

- Mom’s Apple Pie: The Heart of the Lesbian Mothers’ Custody Movement. San Francisco, California. Directed by Jody Laine, Shan Ottey, and Shad Reinstein, 2006.

- Rivers, Daniel Winunwe. Radical Relations: Lesbian Mothers, Gay Fathers, & Their Children in the United States since World War II. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

- Ross, Loretta, & Rickie Solinger. Reproductive Justice: An Introduction. Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2017.