by Xingkang Chen (Victoria)

In this podcast, we will dive into the fight for reproductive justice through the lens of the Mohawk community at Akwesasne. The struggles of communities like the Mohawk people of Akwesasne offer essential lessons to the ongoing threats of bodily autonomy and environmental justice, especially in this era after the overturn of Roe v. Wade and under Trump’s second presidency. What did they do in the past, and what insights can we gain from the past for the future?

Transcript

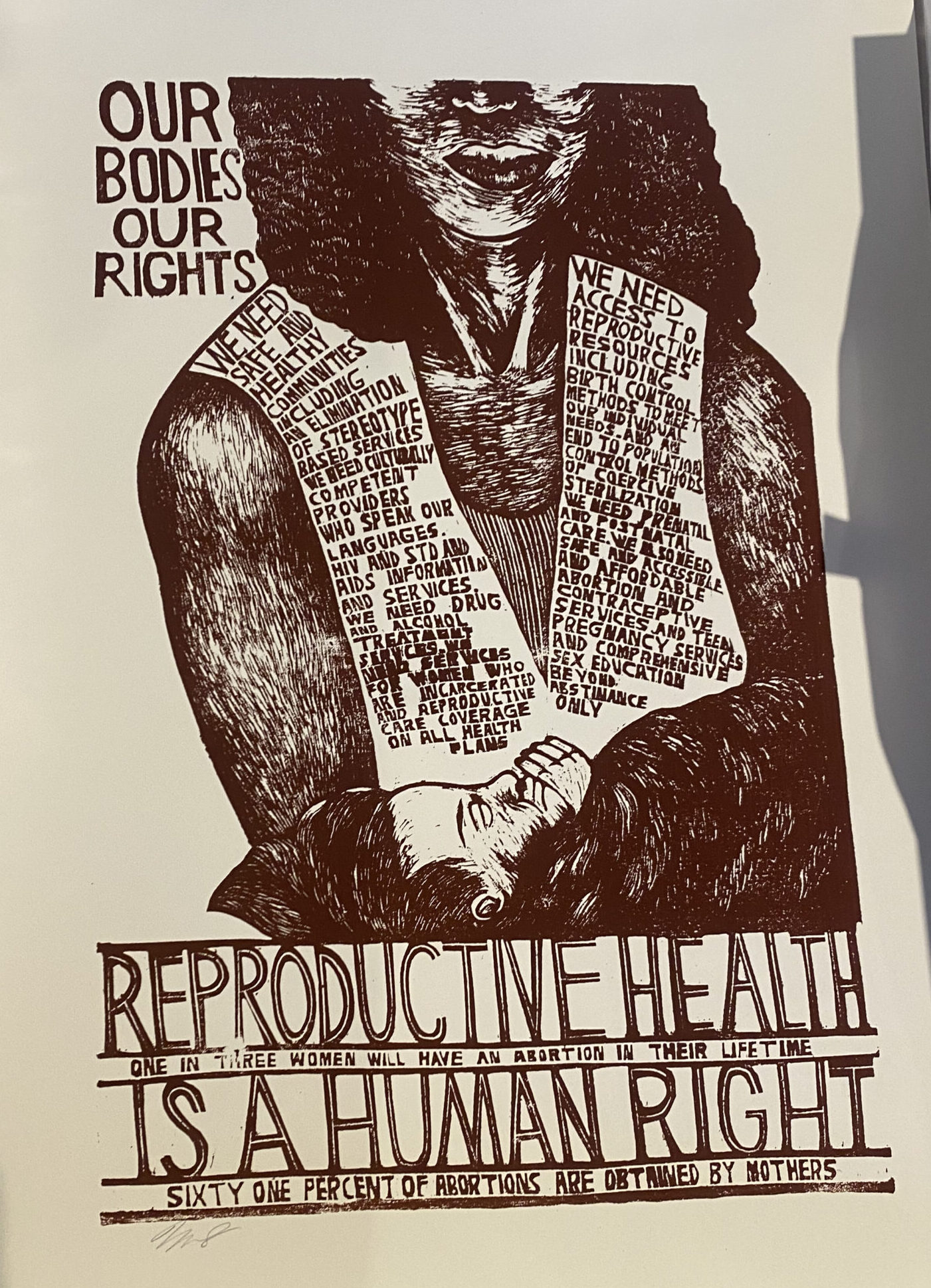

Welcome to Feminist Voice! I’m Victoria Chen. In this episode, we’ll dive into the fight for reproductive justice through the lens of the Mohawk community at Akwesasne. As we navigate the aftermath of the overturn of Roe v. Wade and face ongoing threats to bodily autonomy, the struggles of communities like the Mohawk people of Akwesasne offer essential lessons. Their fight for environmental justice is also a fight for reproductive rights—reminding us that the health of our bodies, families, and communities is deeply tied to the health of the environment.

Here’s a startling fact to get us started: on May 15, 2024, scientists from the University of New Mexico found microplastics lodged in human and dog testicular tissue.1 Alarming, right? But it’s just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to how pollution affects our reproductive health.

And while this study made headlines, these issues are far from new. In fact, communities like the Mohawk people of Akwesasne have been fighting against environmental toxins for decades. Their story reveals how pollution isn’t just an environmental crisis—it’s a reproductive justice crisis intersected with economic inequality and systemic oppression.

Akwesasne is a Mohawk reservation spanning the St. Lawrence River, straddling the U.S.-Canada border.2 With its remote location and access to hydroelectric power, it became an industrial hub, hosting aluminum smelters, chemical plants, and paper mills.3

Among them was the General Motors foundry, less than 100 yards from Mohawk homes. The manufacturing process used PCBs, or polychlorinated biphenyls, and other chemicals that are harmful to humans and wildlife. These toxic substances seeped into the soil, groundwater, and the St. Lawrence River.4

The food and environment are no longer safe for Mohawk people. This is especially devastating for women and new-coming babies.

Katsi Cook, a Mohawk midwife and activist, put it this way: “There was PCBs in mothers’ milk. And not only PCBs but agricultural products: Marax, which is a flame retardant, all kinds of — hexachlorobenzene — different chemicals that at that time, it astonished me. And I began to realize, We’re part of the dump. If this is in the river and in the GM dump, then the dump is in us.”5

Katsi Cook didn’t just see this as an environmental issue—she lived it. As a midwife, she watched infants born with birth defects, including deafness, intestinal abnormalities. She knew this had to change.

In 1985, Katsi launched the Mother’s Milk Project. She brought in scientists from the New York State Department of Health and the State University of New York School of Public Health to analyze breast milk samples. She didn’t stop there—she also trained about 125 Mohawk women to become health researchers and advocates.6

Katsi’s persistence, along with the work of Jim Ransom, former director of the St.Regis Mohawk Tribes Environmental Office, achieved a monumental task: They studied how PCBs were moving through the entire food chain at Akwesasne, from fish to wildlife to breastmilk.2

So, what did they find?

The results were shocking: PCB levels in wildlife were off the charts. The highest PCB level was found in a shrew. It contains an astonishing 11,522 parts per million of PCBs, far beyond what is considered safe for any living creature. For context, anything above 3 parts per million in poultry fat is unfit for human consumption, and 50 parts per million in soil is considered hazardous waste.3

These toxins didn’t stop at wildlife—they made their way through the food chain into the bodies of local women, infants, and children. The Mother’s Milk Project studied fifty new mothers over several years, and it found that Mohawk mothers who ate fish from the St. Lawrence River had PCB levels in their breast milk that were 200% higher than the general population.2

PCB pollution is not just damaging to the environment, it also affects reproductive health and justice.

Elevated estrogen levels caused by PCBs can lead to earlier puberty and menopause.6 In the Mohawk belief, a woman is the first environment where a baby lives. When women’s health is compromised, how can they provide a safe and healthy environment for their children? Reproductive justice simply isn’t possible without ensuring the well-being of women first.

PCB pollution doesn’t just harm reproductive health—it hits hardest in communities already struggling with poverty. This makes it an intersectional issue, where economic inequality and environmental harm collide. With the river contaminated, families lost their primary protein source. Many turned to cheaper, processed foods, leading to skyrocketing rates of diabetes and other health issues.

As Henry Lickers, a Mohawk environmentalist, explained, “Protein has become scarce—and expensive—in a community where more than 70% of people rely on public assistance. Instead of cattle, fish people are eating macaroni, potatoes, and bread. And that’s in a population where 50 percent of the people over the age of 40 are confirmed diabetics.”3

Henry Lickers’ words are alarming: it’s impossible to raise children in a safe, healthy environment when so many people in the community are struggling with their own health.

This is not a localized issue, but a pattern we see globally. Wealthy urban populations can afford organic, unpolluted food, while marginalized communities bear the brunt of environmental degradation. Indigenous people like the Mohawk community and even entire nations in the Global South, like those agricultural and climate-dependent countries in Africa, face the harshest consequences of a system they didn’t create. This is an intersectional issue with systematic oppression. Just as toxic pollutants disproportionately harm the Mohawk community due to their economic vulnerability, we see the same forces of economic inequality at play in the post-Roe world, where Black, Indigenous, and low-income women are most vulnerable to the loss of reproductive rights due to the deprivation of access to healthcare, abortion services, and affordable contraception.

For the Mohawk people, the effects of pollution go beyond physical health—they extend to the very core of the community’s identity.

As Katsi Cook said, “Our traditions survive in doing things the Mohawk way; our whole ceremonial life, our cosmological life, is based on nature. Without that river, we lose Akwesasne.”3

The pollution doesn’t just poison the fish—it disrupts the spiritual practices, weakens tribal identity, and tears at the cultural fabric tied to the river and the land. The Indigenous belief that “land is our mother”7 reflects how environmental harm threatens not just physical survival but cultural survival as well. Reproductive justice cannot be achieved when children are parented in an environment that is neither physically nor culturally healthy.

This is not just a historical issue—it’s one we’re still grappling with today. From the polluted waters in Akwesasne to the toxic air in Flint, Michigan, the legacy of industrial exploitation is still with us. The same forces that poisoned the Mohawk community are still threatening the health and autonomy of people everywhere.

So, what can we learn from the Mohawk community at Akwesasne?

First, environmental justice is reproductive justice. Protecting the environment isn’t just about saving rivers or reducing emissions—it’s about safeguarding the health of mothers, children, and entire communities.

Second, intersectionality is key. Pollution doesn’t affect everyone equally. Those already facing economic or social disadvantages are often hit the hardest, whether it’s the Mohawk people or farming communities in Africa battling climate change.

And finally, resistance works. The activism of Mohawk women like Katsi Cook shows us how community-driven solutions can dig up hidden injustice and make a difference.

We live in a time when environmental policies often prioritize profits over people. Under Trump’s leadership that pushes agendas like “Drill, Baby, Drill,” it’s easy to feel powerless. But history teaches us that collective action can make a difference.

The fight for reproductive justice is far from over, and the lessons we can learn from past resistance are critical. Whether advocating for stricter environmental protections, supporting reproductive rights, or holding corporations accountable, we must continue to resist the forces threatening our bodies, our communities, and our future.

We must all follow the lead of the Mohawk women and others who’ve fought tirelessly against the injustice. The fight for a healthy environment is also the fight for justice—for the most vulnerable, for the future of our planet, and for all of us.

Thank you for listening to Feminist Voice. I’m Victoria Chen, and I’ll see you next time as we explore more stories at the intersection of gender, justice, and resistance.

Reference

[1] SciTechDaily. 2024. “Plastic Invasion: Microplastics Found Lodged in Human and Dog Testicular Tissue.” SciTechDaily, June 6, 2024. https://scitechdaily.com/plastic-invasion-microplastics-found-lodged-in-human-and-dog-testicular-tissue/.

[2] Katsi Cook, Mohawk Mothers Milk, and PCBs. Katsi Cook papers, Sophia Smith Collection, SSC-MS-00528, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts. https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/128960 Accessed November 28

[3]Pollution defiling a way of life. Katsi Cook papers, Sophia Smith Collection, SSC-MS-00528, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts. https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/2/resources/829

[4]A Partnership Study of PCBs and the Health of Mohawk Youth: Lessons from Our Past and Guidelines for Our Future. Katsi Cook Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Mass. https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/129061 Accessed November 28, 2024.

[5] Cook, Katsi. Interviewed by Joyce Follet. Video recording, October 26-27, 2005. Voices of Feminism Oral History Project, Sophia Smith Collection.

[6] Silliman, Jael, Marlene Gerber Fried, Loretta Ross, and Elena Gutiérrez. 2016. Undivided Rights: Women of Color Organizing for Reproductive Justice. Haymarket Books.

[7] Arvin, Maile, Eve Tuck, and Angie Morrill. 2013. “Decolonizing Feminism: Challenging Connections Between Settler Colonialism and Heteropatriarchy.” Feminist Formations 25 (1): 8–34. https://doi.org/10.1353/ff.2013.0006.