Mary Randall

Transcript

Hello, and welcome to The Quinacrine Files. I’m your host, Mary and this is my contribution to the Listening for Reproductive Justice podcast project. With the overturning of roe earlier in the year, the topic of reproductive justice is more fraught than ever. In fact, it’s been a fraught topic for as long as I can remember, and really even before that. The hyperfocus on abortion rights isn’t doing us any favors. I wanted to talk about something else. Don’t get me wrong, the right to abortion is crucial. I can think of at least 10 women off the top of my head, and who I know personally, whose lives have been profoundly impacted by abortion, as well as my own. But reproductive freedom encompasses more than just the right to abortion. In Combahee at 40 Loretta Ross writes, “abortion advocacy alone inadequately address[es] the intersectional oppressions of white supremacy, misogyny, and neoliberalism.” While all kinds of women seek abortion care, we are not all subjected to the same kind of treatment (or mistreatment) by healthcare providers and the state. The right to abortion is only a small fraction of what it means to have bodily autonomy.

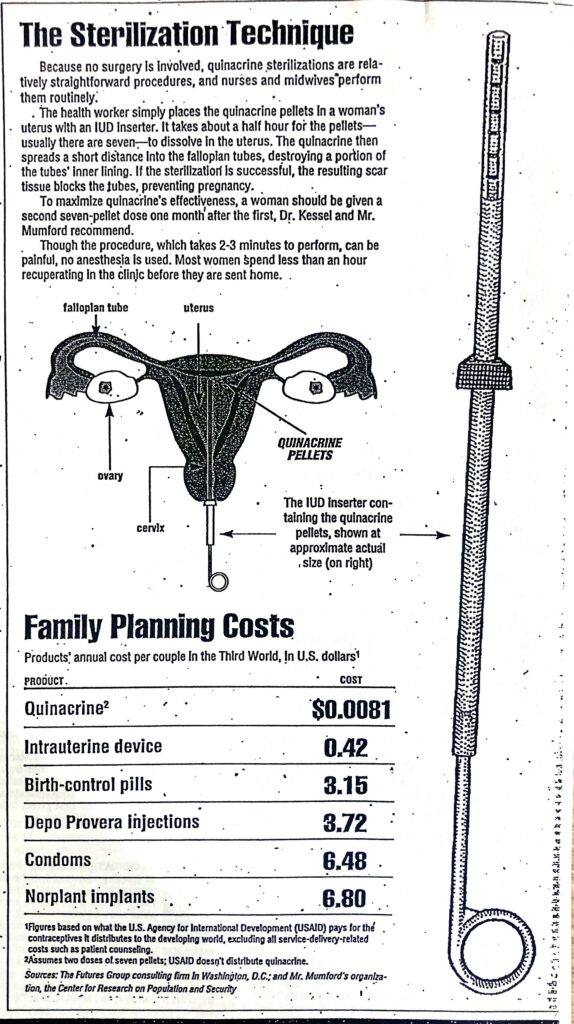

I was struggling to think of what to talk about here. The options felt endless, and I couldn’t seem to find focus. Then our class took a trip to the archives. It was there that I had the happy, and maybe a happy is a weird word choice here, accident of mistakenly grabbing box 11 of the Betsy Hartmann papers. I had no idea who she was but decided to look around anyway (it’s a pretty big box and I had already carried it across the room). Immediately something caught my eye. Almost every file in the box was labeled with the word Quinacrine, which is really similar to Quinine, a word I had just learned about—could the two be related? Quinine is a drug used to cure malaria. In my research for another class, I had recently been reading about the British acquisition of cinchona trees in the Andean region of South America, to be grown in India as plantation crops in the 1800’s. As the British were colonizing areas prone to malaria outbreaks, they needed a cure that could be widely distributed to their troops. As it turns out, Quinacrine is a derivative of Quinine, and in the 1970’s, a Chilean gynecologist began experimenting with a new method of sterilization on women. By inserting a liquid form of Quinacrine into the uterus, which would burn the fallopian tubes, scar tissue would develop and make pregnancy impossible. Well, close to impossible. Ectopic pregnancies still occurred in many cases and despite them being potentially fatal, this form of sterilization became increasingly popular. This, of course, resulted in a myriad of complications for the women who underwent this treatment. From severe pain to uterine adhesions, damages to the vaginal wall, and even a few deaths. Eventually, there would be a pellet form developed that would be applied with the use of an IUD inserter, making the procedure easier, cheaper, and slightly less caustic. Only slightly though.

Despite the harmful nature of this method and a lack of proper testing, two doctors from the United States who had an odd obsession with “overpopulation”, especially in poor communities, began funding the spread of Quinacrine sterilization without proper clinical trials, or even FDA approval. For over a decade the drug was distributed to doctors all over the world in an effort to curb population in poor countries. Over 100,000 women in the global south, and some in the United States were sterilized using this method before the drug was finally banned in 1998.

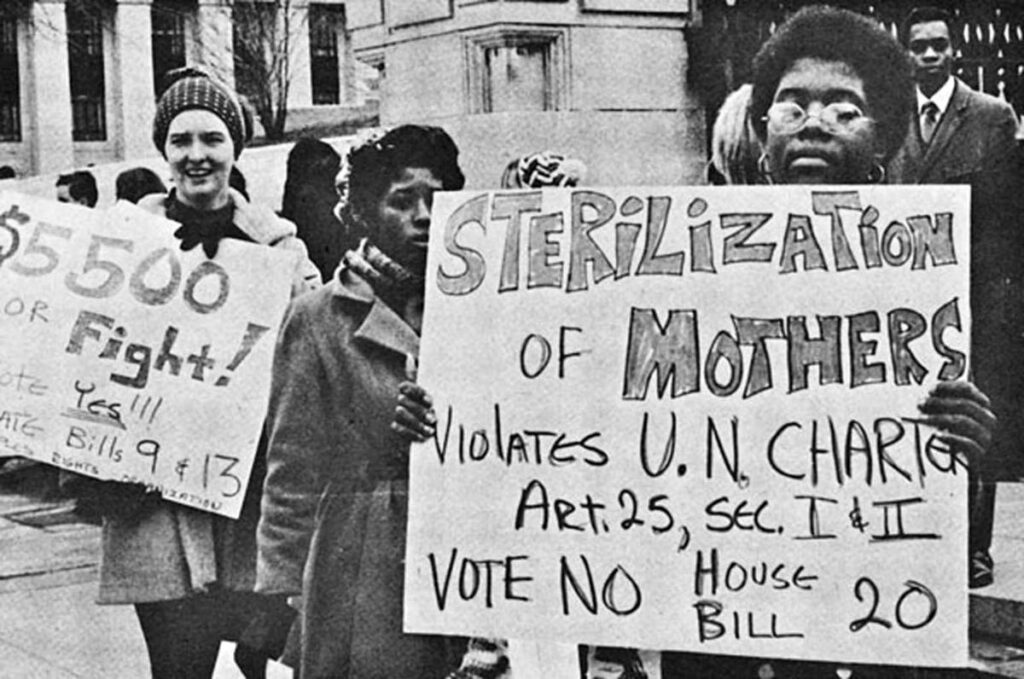

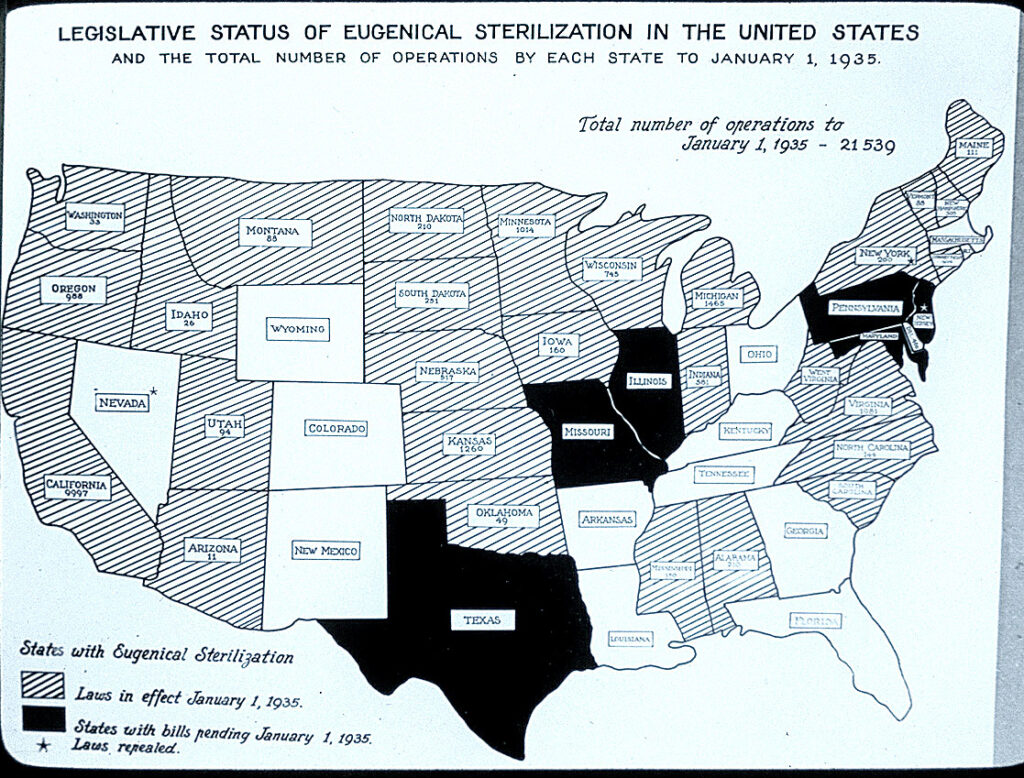

But that’s only a blip in the long history of doctors in the United States using the science of eugenics and cries for population control to justify the sterilization of populations deemed undesirable. In fact, Hitler praised the United States for our sterilization policies and Nazi doctors even modeled their practices after them.

In the 1960’s, civil rights activist, Fannie Lou Hamer coined the term “Mississippi Appendectomy.” Many Black women and young girls, like Hamer herself, went to the doctor for commonplace procedures, and left having been sterilized, often without their knowledge or consent. Hamer estimated that over half of all Black women in Mississippi who went to the hospital received this treatment and she turned out to be right. Estimates range anywhere from 40-60 percent. And a staggering ninety percent of these procedures were paid for by the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

Additionally, the Indian Health Service is believed to have sterilized anywhere from twenty-five to fifty percent of Native American women and girls as young as fifteen years old without their knowledge or consent. That is, of course, in addition to the state removing around of 1/3 of Native American children from their parents to be raised in white households and residential schools. Similarly, after Puerto Rico after became a US territory, in an effort to control population growth on the island, approximately one third of Puerto Rican women of childbearing age were sterilized between the 1930’s and 1980.

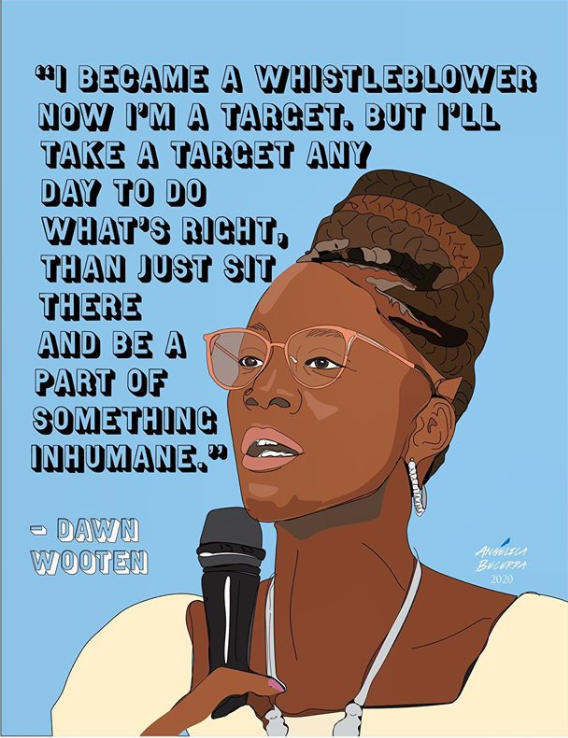

So why does all of this matter now? Well, besides the importance of historical context, it matters because it is still happening. In 2020 Dawn Wooten, a nurse in an ICE detention center in Georgia, filed a whistleblower report claiming dozens of women who had reported having been sterilized without their consent. Sterilizations in the detention center were so prevalent, detainees had taken to calling the gynecologist “The Uterus Collector.” Since this story broke, many more women have come forward with similar claims and Dawn Wooten has had to leave her home, has struggled to find work, and has dealt with threats concerning the safety of her family.

Besides all the grim details of these stories, they have another thing in common: we would have likely never known what was happening to these women without the voices speaking out about these injustices. And continuing to speak out, against opposition, sometimes against threats to their safety, and probably when it felt like no one was listening, they kept speaking. People in power will always try to exert their power in nefarious ways but we can use our voices and strength in numbers to speak out against them. The forced sterilization of Black women would have likely kept happening without voices like Fannie Lou Hamer, Loretta Ross, and Dorothy Roberts. Quinacrine sterilization would probably still be legal if it weren’t for journalists like Betsy Hartmann writing articles and keeping meticulous records on the subject. And we would have no idea what is happening inside ICE detention centers without whistleblowers like Dawn Wooten putting their jobs and personal safety on the line to speak out against these injustices.

As I mentioned before reproductive justice is about more than just access to abortion. It’s about everyone having the right to choose what we do with our bodies and having access to appropriate, affirming, consensual care. Thanks for listening and may we all be as brave as those who came before us and continue speaking truth to power and elevating the voices and experiences of the most marginalized among us.

Bibliography

Amiri, Brigitte. “Reproductive Abuse Is Rampant in the Immigration Detention System | News & Commentary | American Civil Liberties Union.” https://www.aclu.org/news/immigrants-rights/reproductive-abuse-is-rampant-in-the-immigration-detention-system.

Ko, Lisa. “Unwanted Sterilization and Eugenics Programs in the United States.” Independent Lens (blog). https://www.pbs.org/independentlens/blog/unwanted-sterilization-and-eugenics-programs-in-the-united-states/.

Manian, Maya. “Immigration Detention and Coerced Sterilization: History Tragically Repeats Itself | News & Commentary | American Civil Liberties Union.” https://www.aclu.org/news/immigrants-rights/immigration-detention-and-coerced-sterilization-history-tragically-repeats-itself.

NAPAWF. n.d. “Whistleblower Reveals Mass Hysterectomies and Other Atrocities Occurring in Detention Center in Georgia.” NAPAWF. https://www.napawf.org/ap-eye/content/2020/9/18/whistleblower-reveals-mass-hysterectomies-and-other-atrocities-occurring-in-detention-center-in-georgia.

NPR. n.d. “ICE, A Whistleblower and Forced Sterilization: 1A: NPR https://www.npr.org/2020/09/18/914465793/ice-a-whistleblower-and-forced-sterilization.

Onyekweli, Nonny. 2020. “Reports of Forced Sterilizations Have Prompted America to Reckon With Its Past.” Shondaland. October 28, 2020. https://www.shondaland.com/act/news-politics/a34497969/ice-forced-sterilizations-american-history/.

Pettus, Emily. n.d. “Black and Hispanic People Have the Most to Lose If Roe Is Overturned | PBS NewsHour.” https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/black-and-hispanic-people-have-the-most-to-lose-if-roe-is-overturned.

Remnick, David. n.d. “The Trials of a Whistle-Blower | The New Yorker.” https://www.newyorker.com/podcast/the-new-yorker-radio-hour/the-trials-of-a-whistle-blower.

Robyn, Linda M. 2018. “STERILIZATION OF AMERICAN INDIAN WOMEN REVISITED: Another Attempt to Solve the ‘Indian Problem.’” In Crime and Social Justice in Indian Country, edited by Marianne O. Nielsen and Karen Jarratt-Snider, 39–53. University of Arizona Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt20061j2.7.

Ross, Loretta J. 2017. “Reproductive Justice as Intersectional Feminist Activism.” Souls 19 (3): 286–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999949.2017.1389634.

Smaw, Eric D. 2022. “Uterus Collectors: The Case for Reproductive Justice for African American, Native American, and Hispanic American Female Victims of Eugenics Programs in the United States.” Bioethics 36 (3): 318–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12977.