By Emily Westfall

This podcast explores how the criminalization of pregnancy outcomes—especially stillbirths—has intensified in the years following the overturning of Roe v. Wade. While public debate focused on abortion bans, a quieter and less visible crisis emerged: vulnerable women, particularly those facing poverty, addiction, or limited healthcare access, have increasingly been investigated, prosecuted, or punished after experiencing pregnancy loss.

Transcript

When the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022, the national conversation focused on abortion bans. But as the dust settled, something else happened—quietly, and mostly to women who were already vulnerable.

Some grieving mothers… started getting arrested.

Today on the podcast: why the criminalization of stillbirth is rising in post-Dobbs America… and what history in the Smith archives can teach us about this moment.

I’m Emily, and this is the sad story of many women around The United States.

A stillbirth is a devastating medical event that results in the death of a baby after 20 weeks of pregnancy. It’s common — about 1 in every 160 pregnancies ends this way. Most causes are medical: infection, placental problems, hypertension. Often, doctors don’t know the cause.

But after Dobbs, the logic of abortion restrictions started bleeding into other parts of pregnancy care. Suddenly, pregnancy loss wasn’t always seen as a tragedy. Sometimes, it was treated like a crime scene.

Across the country, mothers have been charged with homicide, child neglect, chemical endangerment… even when the medical evidence is uncertain or nonexistent. In some cases, police officers show up in the hospital room before the grief even begins to settle.

And while this sounds new, it isn’t.

The archives tell us that controlling pregnant bodies has a long history.

When I looked through the Smith College archives, I wasn’t looking for stillbirth specifically. I was looking for clues — moments in the past when women were blamed, investigated, or surveilled for their pregnancies.

I found a 1977 Planned Parenthood memo discussing “pregnancy surveillance” laws, which were being proposed to monitor drug use among pregnant women. The memo warns: “Policing pregnancy will not improve outcomes. It will only drive women away from care.”

That was nearly fifty years ago.

I also found materials from Sistersong — the Black-led reproductive justice collective founded in 1997. Their early mission statements emphasized something we often forget: reproductive justice isn’t just abortion access. It’s the right to have a child, the right not to have a child, and the right to parent children in safe and healthy communities.

Those archives felt like they were talking directly to this moment.

Because the mothers being criminalized today are overwhelmingly poor, disproportionately Black or Indigenous, and often already isolated from healthcare.

All of it helps us see that what’s happening today isn’t random — it’s part of a much longer pattern.

One legal scholar, Jill Wieber Lens, describes this moment as a “quiet crisis.”

Because the criminalization of stillbirth isn’t always headline news. These aren’t high-profile abortion prosecutions. These cases often involve women who are already marginalized — people who don’t have lawyers or advocates or even stable prenatal care.

Many arrests happen when hospitals call the police based on suspicion rather than evidence. Sometimes, it’s simply because a grieving mother can’t explain why her pregnancy ended — even though medically, we often can’t explain stillbirth.

There are stories of women jailed for months while autopsies later found no wrongdoing at all.

But the damage is already done — trauma, grief, loss of other children to foster care, and a community message: if you seek help, you may be punished.

And the archives help us see the danger here.

If policing pregnancy discouraged people from seeking care in the 1970s…

it will do the same now.

But history doesn’t only warn us.

It also shows us how people resisted.

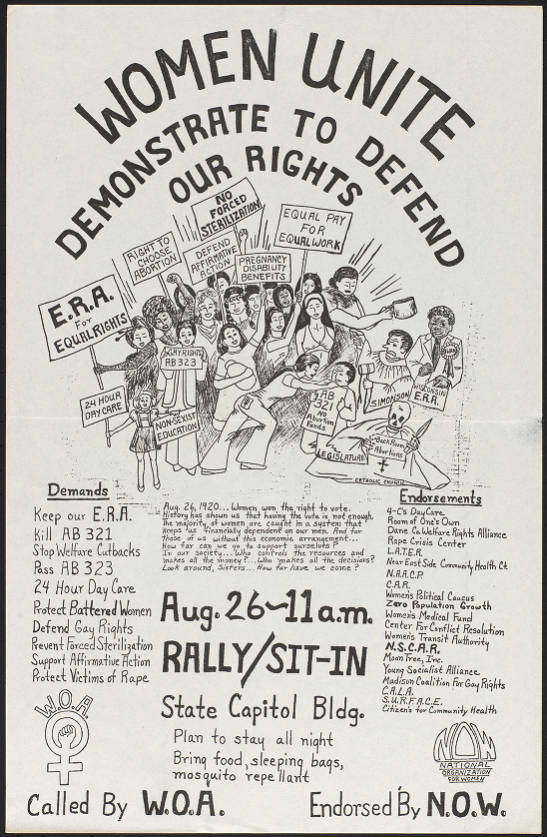

From the Women’s Health Movement of the 1970s to the reproductive justice movement of the 1990s, activists have long fought for something deeper than “choice.” They fought for dignity, for community care, and for narratives that centered the people most harmed.

In the Sistersong collection, I found flyers from early teach-ins in the 2000s. One quote sticks with me:

“We tell our stories because silence is used against us.”

That feels like exactly what this moment calls for.

The criminalization of stillbirth thrives in silence — in the assumption that these cases are rare, or that the women involved must have done something wrong.

But reproductive justice says otherwise:

Everyone deserves medical care without fear.

Everyone deserves to grieve without suspicion.

And everyone deserves to have their bodily autonomy respected, even — and especially — in moments of loss.

So what do we do with this history?

To me, the lesson is this:

When policy shifts hard in one direction — like it did after Dobbs — the people most affected aren’t always the ones in the headlines. Sometimes they’re the ones we don’t even see.

The archives show us that pregnancy policing is not new. The targets are not new. The harms are not new.

But the reproductive justice movement has also shown us, for decades, how to fight back:

by centering lived experience,

by telling stories that would otherwise be erased,

and by refusing to let grief be treated like guilt.

And maybe that’s the story we need now.

Thank you for listening.

I’m Emily, and this has been “When Grief Becomes a Crime”

References

Scholarly & Legal Sources

Lens, Jill Wieber. Criminalization of Stillbirth. SSRN Working Paper, 2023.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4454681

Wagner, Jennifer. “‘The Birth of Death’: Stillborn Birth Certificates and the Problem for Law.” Social Science Research Network, 2020.

PDF available on SSRN.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). “Stillbirth.” ACOG Women’s Health FAQs. Updated 2024.

https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/stillbirth

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). “Management of Stillbirth.” Practice Bulletin No. 102. Revised 2020.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). “Addressing Social and Structural Determinants of Health in the Delivery of Reproductive Health Care.” Committee Statement No. 11, 2024.

Historical / Primary Sources (Sophia Smith Collection)

Women Organize for Action (W.O.A.). Women Unite: Demonstrate to Defend Our Rights (rally flyer). ca. 1970s. National Organization for Women (NOW) endorsement. Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College Special Collections.

Planned Parenthood Federation of America Records (PPFA). Patient education pamphlets and public-health materials on prenatal care, pregnancy, and maternal health. Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College Special Collections.

Reproductive Rights National Network (R2N2). Internal memos and policy materials on surveillance of pregnant people, 1970s–1980s. Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College Special Collections.

SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective Records. Conference flyers, mission statements, and reproductive-justice educational materials, 1990s–2000s. Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College Special Collections.

Voices of Feminism Oral History Project. Interviews with reproductive-health activists, midwives, and organizers. Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College Special Collections.

For Further Reading

A Social History of Stillbirth: Pregnancy, Loss, and Public Health in America – Janet Golden

National Advocates for Pregnant Women (NAPW) — “Cases & Data on Criminal Prosecutions of Women for Pregnancy Outcomes”