The Archive

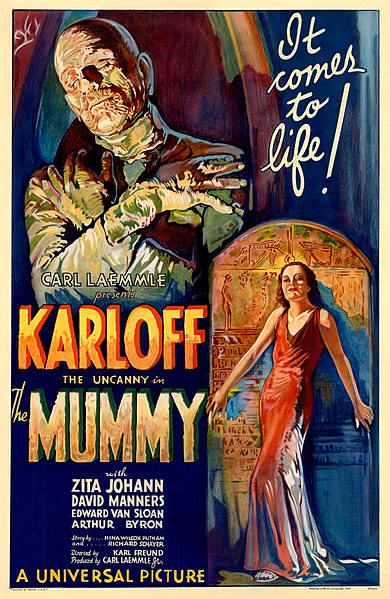

Following the “mummy craze” of the Victorian era, the early twentieth century soon ushered in its own era of Egyptomania. In 1922, the rediscovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun in Egypt’s famous Valley of Kings covered the front pages of newspapers across the globe, rekindling a fascination with Egyptian culture that had now spread internationally. The subsequent release of Karl Freund’s classic horror film The Mummy in 1932, in which a group of archaeologists unwittingly resurrects a mummy through long-lost ancient Egyptian magic, further fascinated the minds of the public with images of an imagined ancient Egypt and its embalmed inhabitants. This collective cultural interest fueled the demand for more research into, and display of, ancient Egyptian art and artifacts.

Yet the twentieth century brought new technologies and philosophies to the display of mummified remains. Where the archaeologists and explorers of the nineteenth century often lacked the equipment, specialized knowledge, and funds needed to conduct efficient and comprehensive excavations, those of the twentieth century benefited from the new knowledge and technological advancements of the industrializing era, propelling the research and display of Egyptian artifacts and remains to new horizons.

A New Horizon of Research

The early to mid-twentieth century offered massive strides in the development of technology and science, launched forward by the societal changes created by Industrialization and warfare. Archaeological sciences benefited from these advancements both directly and indirectly, providing archaeologists and historians with the tools needed to conduct more efficient research. In the 1920s, advancements in the field of dendrochronology by scientists like A. E. Douglas allowed researchers to determine the approximate age of archaeological sites and artifacts containing or constructed from wood. The subsequent development of radiocarbon dating in the mid-twentieth century provided archaeologists with a precise, reliable method of dating specimens, allowing for a deeper level of research of ancient histories.

CT Scanning

One of the most significant technological developments for the study of mummified human remains specifically, however, was the advent of the CT scan, or computed tomography scan. The creation and patenting of the CT scanning procedure by William Henry Oldendorf in 1963 and its subsequent utilization by archaeologists revolutionized the way in which researchers handled and analyzed artifacts, not exempting human remains. Presented with a method of examining materials in a non-invasive manner, Egyptologists soon realized this technology could allow for the research of mummies without necessitating their physical unwrapping, a practice that had become an expected part of mummy analysis.

Meeting Hatshepsut

In 2007, archaeologists demonstrated the value of CT scanning to Egyptology, as the technology helped rediscover the mummies of one of the most noteworthy rulers in ancient Egyptian history. Having been all but erased from the Egyptian historical cannon by her successors, the memory of Hatshepsut, Pharaoh of Egypt in the mid-fifteenth century BCE, was long forgotten in history, along with her mummified remains. However, the discovery of tomb KV60 in the Valley of Kings in 1903 offered a glimmer of hope. Two mummified women resided in the tomb, as well as a canopic box marked with the name of Hatshepsut. While the former technologies of the nineteenth century would have prevented further research of the mummies at hand, CT scanning technology allowed researchers to examine the inside of the sealed canopic box, which they found contained mummified organs and a single tooth, removed in the mummification process. Realizing one of the mummies in the same tomb was missing a tooth in her jaw, researchers crafted 3D models of the tooth and jaw, utilizing the CT scans they had collected. Lining up the two models, the archaeologists were able to confirm that the tooth and jaw matched, identifying the mummy of Hatshepsut after thousands of years.

Pursuing Ethical Research

More recently, the advent of the CT scan has allowed archaeologists and historians to reexamine the previously accepted practices of handling mummified remains in a new, ethically-minded light. While unwrapping mummies was once a commonplace, if not expected, occurrence, museums have more recently turned to reject this practice. The invasive nature of physically unwrapping mummies makes full conservation of the remains’s original state near impossible. Thus, museums like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York have ceased their act of mummy unwrappings in their research department. In “Making The Met, 1870–2020: A Universal Museum for the 21st Century,” author Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis explores this change, reflecting on the museum’s past choice to unwrap the mummy of a man named Wah, and how they would handle this research differently today:

“An X-ray of his mummy in 1939 demonstrated that Wah was buried with extensive jewelry. On the basis of the X-ray, the mummy was unwrapped, and a stunning collar of faience beads, which accompanies his funerary mask in this display, was exposed. The use of an X-ray is an example of The Met’s embrace of modern technology to study objects in its collection. At the same time, the label notes that today no one would unwrap a mummy but that the jewelry would be recreated digitally.”

“Making The Met, 1870–2020: A Universal Museum for the 21st Century,” 326.

This shift to a preference for non-invasive forms of research on human remains marks a stark change from the philosophies of nineteenth-century scholars, who practiced and even actively encouraged the unwrapping of mummified remains. The advent of procedures such as the CT scan allowed this shift to more conscious research of mummified remains to occur, a shift that likely would not have been possible without the creation of these technologies.

Explore a Mummy CT Scan

In April of 2021, a team of Polish archaeologists stated that they had discovered the first known mummy of a pregnant woman. Her identity is still unknown, though the researchers estimate she was between the ages of twenty and thirty and died sometime in the first century BCE. Through the use of CT scanning, archaeologists have been able to collect this information without unwrapping the mummy’s bandages, keeping the body and items inside in place. Click below to learn more about this mummy and the power of CT scan technology in archaeology.