Elliott Erwitt began capturing photographs in 1948. In an illustrious career, his photography took him around the globe, to explore political and social unrest around the world. Erwitt’s photography is known for a biting sense of honesty and an ability to peer into a subject’s soul with blunt humor. Nowhere is his expertise more obvious than in his Son of Bitch portfolio, centering on the critically human subject of dogs.

The humor of Erwitt’s dogs often comes from the way they expose or contrast their human companions with their unimpeded honesty. In USA, for example, the dog’s bright and excited face, its fluffy upturned belly open for pats, defies the reserved and conventional posture of the family’s portrait.

In Brighton, England, however, the dog makes clear its distaste for the posed portrait. While the woman puts on a smile, either oblivious to the dog’s discomfort or deliberately ignoring it, the dog feels no pressure to conceal its feelings. There’s no posing here: it wants its opinions known and respected.

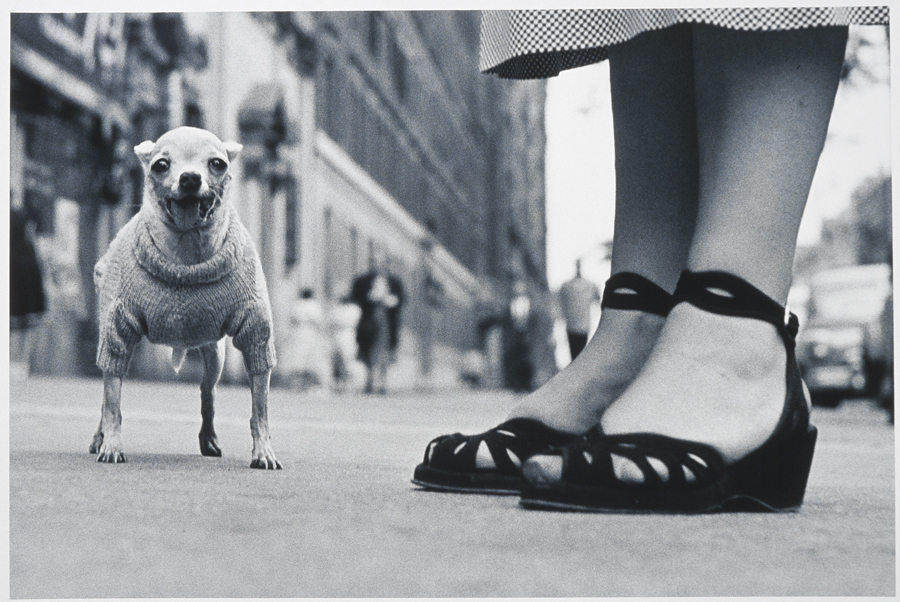

“People like to point out that it’s taken from the dog’s point of view, but the dog, of course, isn’t surprised by that, as you can see. He’s completely ignoring the person next to him, and her point of view.”

One of Erwitt’s most famous portraits, this tiny chihuahua is happy, fashionable, and enjoying life. Just as it is the biggest item in the image’s frame, it fills its whole world. Though its sweater and the prim heels of its owner imply a deep connection with its human companions, they are secondary to the dog’s simple pleasures.

Many of Erwitt’s portraits, like those above, flesh out a blunt sense of humor. They poke fun at human behavior with the open candor of the dog’s personality, which is often at odds with what humans want or expect. Their absorbing and open personalities are the most honest thing in the room, making them the endearing best friend we know dogs to be.

Yet Erwitt’s dogs are not merely counterparts to humans, revealing their idiosyncracies and oddities. In his work, dogs are extraordinarily human themselves.

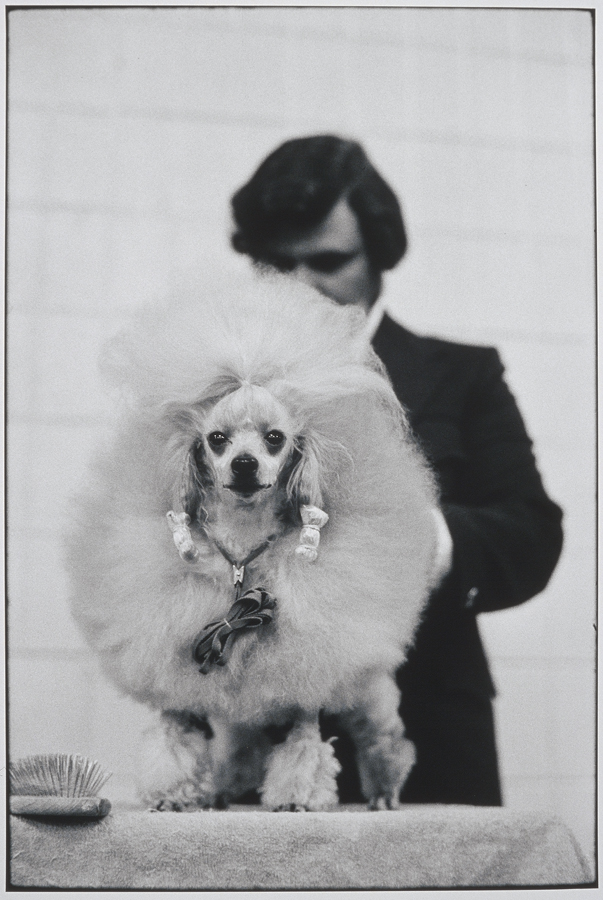

Erwitt’s ability to flesh out a dog’s personality doesn’t end with his ability to capture irony. In fact, he’s able to draw something deeper out of the dogs, which illustrates just how human dogs can be. In New York, 1973, we see the show dog’s eyes directly. The dog is equal parts smug and bored, putting up with laborious preparation for its polished appearance. It’s a remarkably person-like expression, of a performer just before they begin the show.

“Every minute, they have to live on two planes at once, juggling the dog world and the human world.” Erwitt, To the Dogs

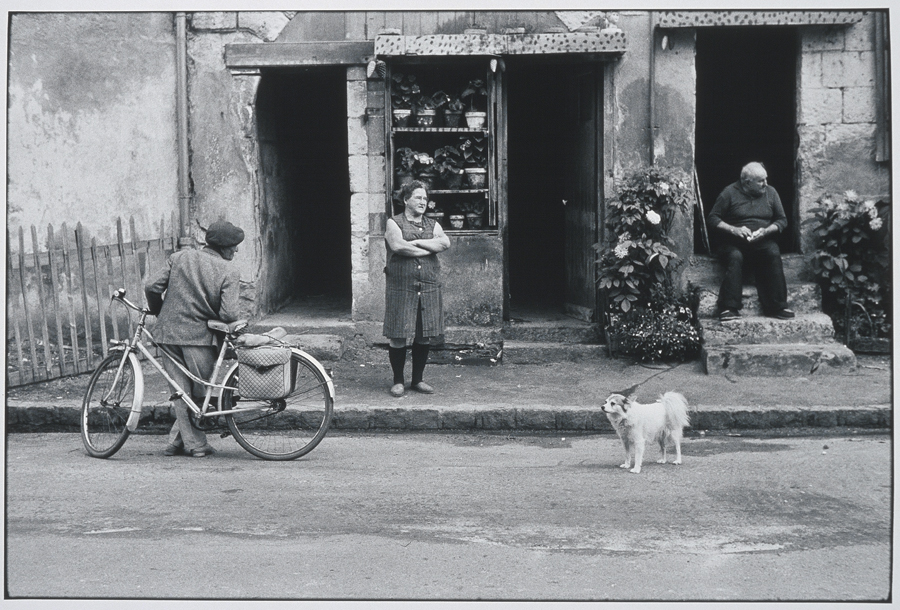

In Loire Valley, the graying, older dog stands with a group of graying, older people. Unlike the earlier images, it’s not betraying a truth about the group. Instead, the dog is a part of this group, judging passersby with them. Although this dog’s a little off the mark, facing the wrong direction, it’s still clearly part of the group.

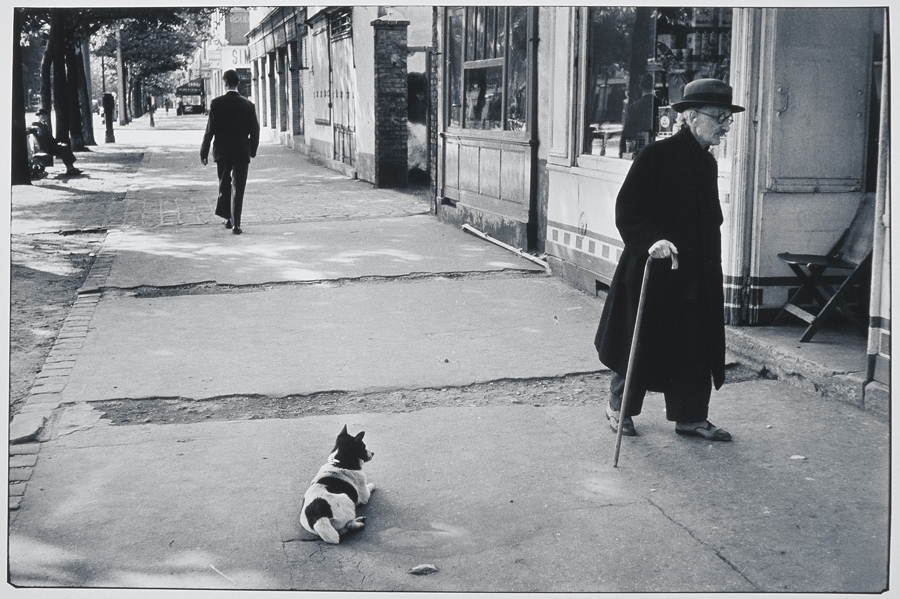

In Man Walking with Cane, it is the man who is an interloper. Although the only image in the Cunningham Center is the pair’s goodbye, Erwitt actually created a series of images for this encounter. They regard each other with fascination, but it is the man who has walked onto the dog’s property. The dog’s poise and stillness convey that this sidewalk is his domain. He bids the stranger hello and goodbye without needing to leave his perch.

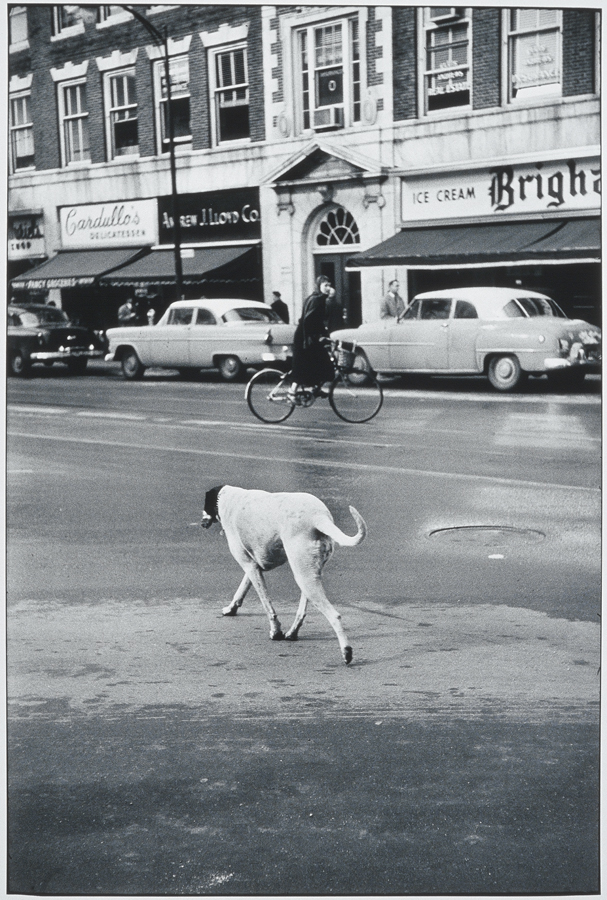

In Cambridge, MA, the dog doesn’t need to perform for or converse with humans. As it navigates the landscape of the city, for a brief moment the mask falls, and in its independence the dog is especially human.

“These are not portraits of dogs. Look again.” – Elliott Erwitt, To the Dogs.

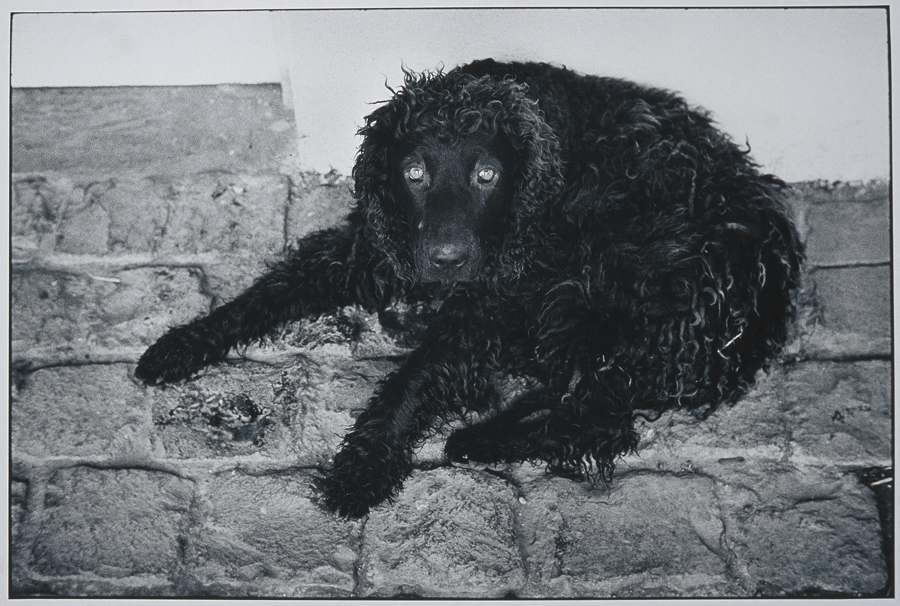

In each of these three portraits of dogs, Erwitt’s sense of humor drops, and instead the dogs’ plain candor is piercing. In Ireland and Paris, the detailed focus on the bright, pale eyes of the dogs gives off the sense that their gaze can cut through lies. If eyes are the window to the soul, then these dogs are not only baring their own to the world: they are appraising ours right back.

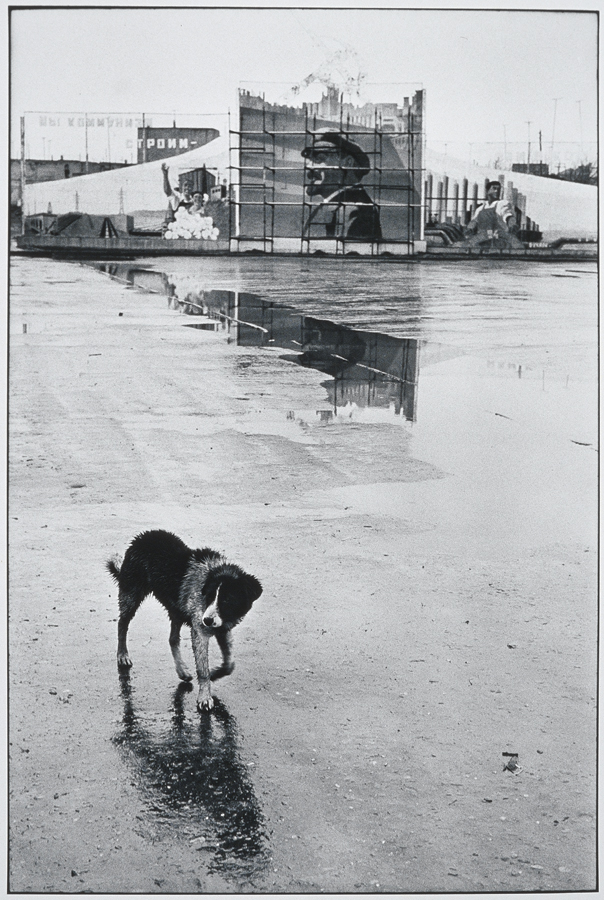

In Siberia, the dog’s eyes are shrouded and unseen. Instead, it is the dog’s exhausted posture, its refusal to meet the camera’s gaze, which is piercing. The dog is small against the city behind him, an especially human scale.

In each of these works, Erwitt highlights the ways dogs enhance our own lives. Their rich personalities, unfailing honesty, and ability to walk between canine and human worlds produce unique insights into their environments. His portraits of dogs reveal stunning, cutting, and humorous truths about man’s best friend.