This apron has flowers embroidered on it in two places. They are clearly hand-embroidered, but the uniformity of the stitching shows that the embroiderer used a pattern.

Aprons like this one were most likely made from kits, often a pre-made apron printed with blue lines indicating an embroidery pattern.

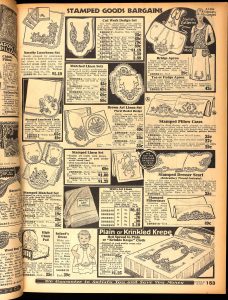

Looking through Sears catalogs from the 1930s, like this one from 1932, you can see that stamped goods, or fabric printed with embroidery patterns were popular items for sale at the time.

The photograph below shows a display of aprons from a South Dakota department store that look very similar to the apron in Smith’s collection, although they are missing the crucial aspect: personalization.

What feels significant to me about this apron is how its former wearer was able to take a mass-produced commodity and imbue it with a personal touch, even if they did use a pattern.