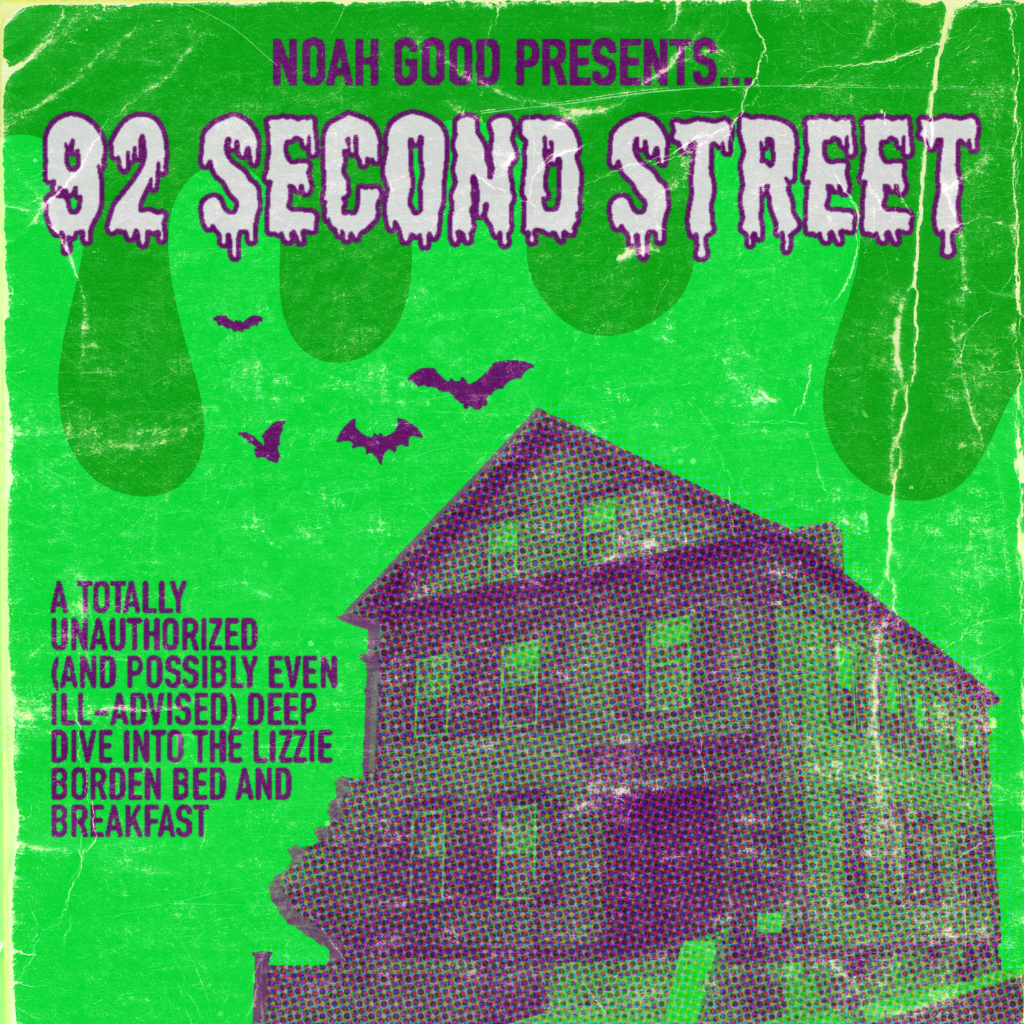

Transcript

Introduction

In 1892, two people were murdered in their home at 92 Second Street in Fall River, Massachusetts. Over a hundred years later, that home was turned into a bed and breakfast and museum named for Lizzie Borden, their daughter and stepdaughter, and their alleged killer.

My name is Noah. In this podcast, I will examine why this B&B was created, how it operates, and the larger cultural implications of its work. I will also explore why this case continues to fascinate and what it suggests about American history writ large.

This is a story in six parts.

Part One: Me

I want to begin by acknowledging my own connection to this research. I’ve been fascinated with this case for a long time. I visited the Lizzie Borden B&B in 2018—more on that later. In my senior year of high school, I did an independent study of the Borden case. I went to a weird high school. For that independent study, I watched and read all of the material based on the case that I had time to digest: an opera, a rock musical, a short story, three movies, and several TV episodes. My final project was a collection of 7 found poems drawing on this material. The semester after, I wrote an essay analyzing the case through the framework of gothic literature. Then I wrote a short story inspired by Lizzie Borden’s life after her acquittal.

Then in my first semester of college, I wrote an essay comparing three houses where a murder took place and examining the impact their treatment had on how their community perceived them. My argument was that it seems that murder houses need to be reframed or destroyed in order for the neighboring community and victims’ families to feel closure. I had originally intended to include the Borden house in my paper, but it became clear during my research that the way that the Borden house has been treated post-1892 is so radically different from the other case studies that including it made the whole paper feel disjointed.

Now, in my final semester of college, I’m returning to my latent obsession with the Borden case, looking again at the B&B.

To be honest, whenever I explain this project to friends, I get embarrassed by the sheer amount of work I’ve done on this case, especially as someone who is an outspoken critic of true crime fanaticism. My friends suddenly discover in a college dining hall that not only have I watched a bazillion movies and musicals about Lizzie Borden, I also slept in her house. It’s not something you drop casually.

If I’m going to ask why the public at large is captivated by this case, I can start by asking myself why I’ve put so much time and energy into my own research about it. So, what fascinates me about the case? One of the main aspects of the history of the Borden case that fascinates me is not the case itself, but the way it has been represented in media. I’m interested in how history becomes narrative and real figures become characters. I’m interested in how certain facts become preserved, some become exaggerated, and some inconvenient facts simply get left out in the telephone game of history.

Part Two: A Brief History of the 1892 Murders

Before I continue, let me give you a brief overview of the murder case itself. This podcast isn’t about the murders themselves, exactly, so I’m not going to go into a lot of detail (because once I start adding details I won’t stop, and we’ll be here for hours). But I can’t just leave you with the one sentence I gave you earlier.

So: on the morning of August 4, 1892, Abby and Andrew Borden were brutally murdered in their home. Abby, who was 64 years old, was killed in the guest room while 70-year old Andrew was killed on the sofa in the downstairs sitting room. Both were killed with a hatchet. Although the murders occurred in broad daylight on a busy street, neighbors and passersby didn’t hear or see anything. There was no apparent motive.

The only other people present in the house were Andrew’s thirty-two year old daughter Lizzie and the family’s maid Bridget Sullivan. Lizzie’s older sister Emma was away as was their uncle John Morse who had come to visit.

Lizzie Borden was arrested and tried for the murders in a very publicized trial. She was later acquitted. No one else was ever charged for the murders and the case has never been solved. After her acquittal, Lizzie Borden returned to Fall River, renaming herself “Lizbeth.” She died in 1927 at the age of 66.

Part Three: Context

So why has this case stuck in popular culture? Why are there so many different works of film, theatre, and literature inspired by the case, and why would there be interest in a bed and breakfast? First, and most obviously, it’s an unsolved case, and people love a mystery. As for why the case is worth studying, I believe it raises important questions about gender, ethnicity, and class in American culture. In his book on the case, Joseph Conforti does an excellent job detailing the case’s historical context. Lizzie Borden, the alleged killer, was an upper-class, Anglo-Protestant woman from a prominent family. She was also a Yankee.

This term generally describes someone who lives in the northern United States or New England. More narrowly, it can be used to describe the part of Fall River’s population who had been born there and whose families had lived there for multiple generations. While the Bordens hadn’t come over on the Mayflower, they could still trace their ancestry to the next best thing: the Puritan migration of the 1630s. By the late nineteenth century, the Bordens had multiplied and become a powerful force not only in Fall River, but in the Northeast at large. Because of her gender, ethnicity, and class, as well as her family’s reputation, the idea that Lizzie Borden would be capable of such a violent act shocked her contemporaries and continues to fascinate people today. If she was found guilty, this would shatter the ideal of Victorian womanhood, a concept which was already being challenged. During the investigation and trial, Lizzie was careful to present herself as a passive, fragile, and genteel lady, and this no doubt helped her case. The Victorian ideal prized female delicacy while Abby and Andrew’s murderer would have needed enough strength to rain down multiple repeated blows with considerable force.

Equally important as Lizzie’s gender was, again, her ethnicity. At the time, Fall River saw a large increase in Irish, French-Canadian, and Portuguese immigrants. This, in turn, led to tensions between these new groups and the Yankees of Fall River. These ethnic tensions are visible in the case. Irish policemen searched the crime scene and an Irish medical examiner studied the bodies—something which many Yankees of Fall River viewed with distrust. Meanwhile, several Portuguese men were brought in for questioning. Notably, several months after the murders and mere days before Lizzie’s trial before the Superior Court, a Portuguese immigrant in Fall River killed his employer’s daughter with an ax. This led some to suspect, again, that the police were wrong. To them, it seemed much more likely that a working-class male Portuguese immigrant would commit such horrific murders, not a woman who was the very image of Victorian womanhood. After all, if Lizzie Borden really wanted to kill someone, she would have used poison, like a good Christian lady. As for the role of ethnicity in the trial, the jury was almost completely made up of Yankees. These Yankee jurors would have had a vested interest in maintaining the reputation of both Lizzie and the Borden family. If an upper-class Yankee woman was found guilty of a brutal murder, that wouldn’t really look good for a group seeking to maintain control of a city in flux.

The Borden case also took place in an interesting context within the history of journalism. The senseless brutality of the murders captured the attention of the national press. Some reporters even sent exclusives to newspapers worldwide. Newspapers sensationalized the case to an absurd extent. In one particular instance, The Boston Globe published an insane article on the case based solely on one man’s unbridled imagination. This man claimed that Lizzie Borden had been pregnant and that Andrew had disinherited her. The Globe was so keen to publish this scoop before any of its competitors that they didn’t stop to verify any of the facts. When The Globe’s story was exposed as false, its editors apologized profusely for slandering Lizzie’s virtue. For many, this episode stoked doubt in the media’s coverage of the case and encouraged sympathy for Lizzie.

The Borden case also occupies an interesting space within the history of forensic science. This was the second time ever that crime scene photos were taken. The first time ever was…you guessed it, Jack the Ripper. The police in the Borden case made several key blunders. For one, they mishandled potential evidence. Further, they failed to rope off the crime scene, which led to contamination. Some people even tracked blood from the guest room. Because the police botched this aspect of the investigation, it seems impossible that the Borden case will ever be conclusively solved.

Part Four: My visit

In August 2018, the summer before my senior year of high school, I visited the B&B. My original plan had been to go with a friend of mine for the anniversary of the murders. We were going to work our visit into our senior capstones, as both of our projects were related to death studies. That’s death with a “th.” She ended up backing out at the last minute, and not wanting to waste the overpriced tickets (and also because I couldn’t drive), I begged my mom to stay the night with me at a murder house.

We drove the hour and a half to Fall River. Before we went to the B&B, we visited the nearby Fall River Historical Society. We watched a Q&A with one of the curators, Dennis Binette (who at the time had recently co-authored a giant tome about the Lizzie Borden case, Parallel Lives). He talked about how in order to do the research right, it was important for him and the other researchers to remain unbiased about Lizzie’s guilt or innocence.

Then we went across the hall to a tiny room filled with letters, journals, and photographs from the case, and Stefani Koorey (another curator) walked us around the room and broke down several misconceptions about the case. I got the sense that every single thing Stefani said could be backed up with pages of research.

Then, we drove about ten minutes to the Lizzie Borden Bed and Breakfast, where we would be spending the night.

Every year on the anniversary of the murder, the B&B does a reenactment—not of the murders, but of the maybe half an hour or so after the murders. Visitors can come in and interview the people in the house and try and solve the case while two actors who I hope are well paid lie under blankets and play dead.

So we walked into the house maybe ten minutes after the reenactment had ended. We checked in, and we walked up to our room, and we passed an employee wiping raspberry jelly blood spatters off the wall.

All the rooms in the house are named after whoever stayed in them, like the “John Morse Room” or the “Andrew and Abby Suite.” Our room was just a storage space when the murders happened, so it had been lovingly named the “Hosea Knowlton Suite,” after the trial’s prosecutor. It was basically in the attic, and it was tiny, and it had a slanted ceiling, AND in the corner there was a big trunk filled with toys and dolls to really up the creep factor.

So my mom and I chilled out for a while—my mom posted on Facebook, “Staying with Noah in the house where Lizzie Borden axed her mom”—and then it was eight o’clock and time for the tour. We went downstairs and finally saw the other guests who were also staying the night. This included a German couple who were visiting the East Coast (they were going to Salem right after this—a real highlight reel of Massachusetts’s proudest moments). There was also a mom and her two kids, a boy who was maybe seven and a girl who was about thirteen. The mom told us that she had actually been to the B&B before—this was her fourth time.

The tour started with our guide telling us, (and I quote), “No photos allowed during the tour. Don’t even AXE me about it.”

Again, a few hours ago, my mom and I had been in a historical society, where we were advised not to even bother looking into this case if we were already biased.

Meanwhile, our tour guide at the B&B was absolutely certain that Lizzie Borden killed Andrew and Abby. She carried around a massive three ring binder with photos from past visitors and would show us the highlights, which included: A towering column of white mist found in Abby’s room! A black fog over the settee on which Andrew Borden was killed! Some very fuzzy lens flares!”

This happened in every room.

And, by the way, our room was apparently “haunted by the spirit of a little boy who lived here sometime maybe and guests have seen him standing by the door with a little ball, which is coincidentally why we have so many toys here, I guess.”

Eventually the tour ended and we went back to our room, and Mom was getting ready for bed. Even though I knew that all the photos from the binder were likely just bad photography and the backstory of our room was mostly likely made up of whole cloth, I was still freaked out. Yeah, I’m not ashamed to say it! I was a little spooked! A reasonable side effect of going through a tour in a dimly lit murder house where the tour guide is doing their best to mess with you. So I said to my mother, who happens to be a pastor, “Hey, uh, Mom? Would you mind… doing a blessing real quick?”

She looked over at me and gave me an indulgent smile before getting her water bottle, and unscrewing the lid. She turned in a circle and flicked water, saying, “God, we ask for peace and serenity, and we release all the spirits that may or may not be in this house.”

And then we watched an episode of The Great British Baking Show on Mom’s laptop, just to be extra sure that the bad vibes were gone.

The next morning we all gathered for breakfast. Part of the B&B’s spiel was that they served you the very food that the Bordens ate on the day that they were murdered! Except not really, because Victorian food was terrible, so instead we had ham, and scrambled eggs, and pineapple slices, and johnny cakes, which are like pancakes, except they’re really, really small, and also terrible.

We were all packed into the [dining] room, which was lined with items related to the murders. I was sitting at the head of the table, and behind me I could hear one of the actors who just so happened to be a psychic medium, giving his elevator pitch to the German couple. The two kids were in the other room playing with the B&B’s complimentary dowsing rods and Ouija board. Right across the table from me was a big glass case with a plastic mold of Andrew Borden’s demolished skull staring right back at me as I ate my scrambled eggs.

Finally, my mom and I checked out, packed our suitcases, and got into the car. Just as we were driving away, my mom turned to look at me, and she said, “You better get me into the best retirement home.”

Part Five: The history of the B&B

The house on 92 Second Street is a Greek Revival home which was built in 1845 and purchased by Andrew Borden in the 1870s. Lizzie and Emma Borden retained ownership of the property until they sold it in 1918. In the following years, 92 Second Street was sometimes a residence, sometimes a site of business. From 1948 to 1995, the house was owned by Smart Advertising, Inc.

In 1996, the owners of Smart Advertising died and left the property to their granddaughter Martha McGinn and long time employee Ronald Evans. That same year, McGinn and Evans opened the house to the public as a bed and breakfast and museum. In an interview for The Roanoke Times, Ronald Evans said, “Look at Salem. I bet they weren’t too happy about the witches 300 years ago, but now the businesses are thriving.” In the interview, the two said they planned to decorate the space with antiques and artifacts from the era, Ouija boards, and a library of books and video tapes related to the case. They hoped to decorate the house with period furniture which would recreate the appearance of the house as it looked in 1892. They noted in interviews that they had received many excited phone calls from prospective visitors, including a couple who wanted to get married in the house. At the time, their most requested room was the guest room where Abby Borden was killed.

The director of the Chamber of Commerce said he hoped that Lizzie would do for Fall River what the witch trials had done for Salem. “If it takes Lizzie to get them here, if she’s the hook, so be it,” he said in an interview with The Boston Globe.

In 2004, Lee-Ann Wilber and Donald Woods bought the property and continued to operate the B&B. The two made several interesting changes to the house to try to make it appear more period-accurate. In 2005, Wilber and Woods decided to demolish Leary Press, a business which had been attached to the house since 1940. They also decided to repaint the exterior of the house a dark green with black trim. These two changes made the house look more like it had in 1892.

In a 2016 interview with The Virginia Quarterly Review, Lee-Ann Wilber detailed the operations of the B&B: “[W]e’re a museum seven days a week. And people can stay overnight five nights a week. I had 150 people come through the house on tour today, and we’re booked at night for the next two weeks.” She added that the B&B was busiest during the lead up to Halloween and in the late summer around the anniversary of the murders. She said that the guest room and Lizzie’s room were the most popular. Visitors included people interested in history and criminal justice as well as people looking for a paranormal experience. One feature of the B&B under Wilber and Woods’ tenure was a sign above the steep staircase reading, “Don’t forget to duck. At least two people have lost their heads in this house.” The gift shop sold bobbleheads of an ax-wielding, blood-spattered Lizzie Borden and coffee mugs with the images of Abby and Andrew’s corpses.

When the interviewer asked if people ever respond negatively to the idea of the B&B, Wilber said, “[M]y reply is: ‘Well, I am keeping a piece of history alive, I am keeping about fifteen people employed.’ I mean, how many people go to Gettysburg? Think of the massive atrocities that took place there—and they have a welcome center.”

The COVID-19 pandemic hit the B&B hard, with many canceled bookings and employee layoffs. In 2020, Woods announced that he and Lee-Ann Wilber were looking to retire and he placed the home on the market.

In May 2021, the property sold to entrepreneur Lance Vaal for nearly $2 million. Vaal is the founder of the company US Ghost Adventures, which hosts ghost tours in over 30 locations nationwide. I was worried by the fact that a man named Lance now owns a historic site—because excepting Lance Bass, there are no good men named Lance. I was even more distressed when one interview featured photographs of him wearing jeans with sandals. I can’t trust a man who would willingly show his feet to the press to be a responsible steward of a site of tragedy.

If I wasn’t already worried, the description of his vision for the Lizzie Borden house was certainly spine-tingling. Of the site, Vaal says, “It’s been one dimensional. I want to add four and five dimensions.” That doesn’t mean anything, Lance! In addition to the original 90-minute house tour, he added a 90-minute ghost tour and a two-hour ghost hunt. As of 2021, he also plans to add a podcast, virtual experiences, themed dinners, a Lizzie Borden whodunit app, and murder mystery nights. He even hopes to attract visitors looking to tie the knot at a crime scene—a real full circle moment for the property. From an ill-advised marriage location you came, and to an ill-advised marriage location you shall return.

He also wants to refit the cellar to create a seventh rentable bedroom. I personally was deeply troubled to learn that the historic cellar where I once saw a massive stack of empty pizza boxes would be disturbed. The parking lot, meanwhile, will host special events, including ax-throwing. Tasteful. When questioned about possible negative responses to this treatment of a murder site, Vaal said, “Who’s being murdered here? I mean, no one’s murdering anybody…We want you to have a good time.” The language Vaal uses to describe his vision is unabashedly commercial. In one particularly bizarre quote, he said, “Lizzie Borden needs to adapt and move into a different century if it’s going to appeal to a new generation.” This of course ignores the fact that the Borden family is not an intellectual property to be licensed or a brand to be refurbished. Vaal also doesn’t answer a key question: Why is it important to ‘get the story into the hands of more people’? Why does this history matter, beyond just being a cash cow? Lance Vaal said, “It means a lot to me, and it is in good hands,” which is something that very trustworthy people say.

Part Six: So What?

Since 1996, the Lizzie Borden house has been billed as not just a bed and breakfast, but a museum. By claiming this identity, the business claims a degree of credibility. The title says, “This is not just a tourist trap, this is an educational and cultural institution.” But by assuming the title of museum, the Lizzie Borden house also takes on the responsibilities of educating the public and providing an opportunity for reflection—responsibilities the house does not fulfill.

The Lizzie Borden house presents a hugely skewed perspective on the Borden murders. We see the case through a fun house mirror. The Borden family becomes stock characters: Andrew is the cruel miser and overbearing father; Abby is the evil stepmother; and depending on your mood, Lizzie is either a deranged spinster or a helpless caged bird who had no other choice. The Lizzie Borden house throws both facts and nuance out the window, preferring instead to sensationalize domestic tragedy. I have even less hope for the latest incarnation of the B&B, which appears to care only about cheap thrills, ghost hunting gadgets, and brand enhancement. The house represents an utter failure to meaningfully engage with either the history of the case or its broader implications.

While the Lizzie Borden house claims to be a museum, it does not present its tragic history with nuance or care, and from all I’ve seen, it does not treat the memories of Abby and Andrew Borden in an ethical or professional manner. As such, the site does not deserve to claim to be a responsible cultural site.

This is especially egregious because the house itself presents such a valuable opportunity to experience history. The floor plan has been relatively unchanged since 1892. When I went on a tour of the house and we walked up the staircase, the tour guide pointed out that at the top of the stairs, you can see clearly into the guest room where Abby’s slain body rested over 130 years ago. I got a chill when she said that. It’s one thing to read about the case or to look at the floor plan, but it is another thing entirely to walk through the house itself.

Experiencing the bizarre layout of 92 Second Street gives you an embodied perspective on the case that would be impossible otherwise. As such, it frustrates me that this geography is used as a cut-rate amusement park ride rather than a window into the complicated lives of the Bordens, lives that we will never be able to fully reconstruct.

The case, and the house itself, both raise such compelling questions, questions which the B&B ignores.

There are the questions of the lawyer: What parallels do we see between these murders and recent criminal cases? How do ethnicity, gender, and class continue to influence criminal justice?

There are the questions of the journalist. What responsibility does the media have in fairly and respectfully representing criminal cases? Why have we chosen to remember the deaths of these two people while the deaths of countless others, both then and now, go forgotten?

There are the questions of the writer. If Lizzie Borden truly did it, how did she live the rest of her life with that memory? If she did it and her family knew it and never said anything, what toll did that silence take on them? How much do we truly know the people around us? How much do we know about ourselves and what we are capable of?

Many of these questions will never have answers, but all of these questions deserve exploration. People who are curious about this case and people who have never heard of Fall River deserve a space to meaningfully contemplate these questions. If the Lizzie Borden house continues to claim to be a museum, it is even more important for it to fulfill this role by providing visitors with an experience that is educational, thoughtful, and ethical.

Above all, Abby Borden and Andrew Borden deserve to be known not as caricatures or tourist attractions or haunted house jump scares. They deserve to be seen as real people, with hopes, fears, and complex interior lives. They deserve that much.