Smith College was founded in 1871 and opened in 1875 with 14 students.[1] Sophia Smith was an unmarried woman in Hatfield, Massachusetts. She lived with her two siblings, both unmarried and survived both. After the death of her brother, Austin, Sophia Smith was left with a large estate. She turned to her pastor, John M. Greene for help. Smith deliberated over several projects, eventually leaving most of the money to found Smith College. The “Last Will and Testament of Miss Sophia Smith” of March 1870, shortly before her death, details “”the establishment and maintenance of an Institution for the higher education of young women, with the design to furnish for my own sex means and facilities for education equal to those which are afforded now in our Colleges to young men.”[2] Sophia Smith also wrote, “It is not my design to render my sex any the less feminine, but to develop as fully as may be the powers of womanhood & furnish women with means of usefulness, happiness, & honor now withheld from them.”[3] Smith was also the first woman to endow a women’s college in America.[4]

founder of Smith College,” Portrait, c. 1858, College Archives, Women’s Education, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts, https://www.smith.edu/libraries/libs/archives/gallery/images/womenseducation/s01_020.JPG

There were many beliefs embedded in educating women and opening a college for women. Before Smith College’s founding in 1871, came three other colleges for women. In 1837, Mount Holyoke was founded as a seminary under Mary Lyon. After this, the founders of Vassar and Wellesley followed suit in 1865 and 1875, respectively. They followed the seminary model, meaning they were in one building.[5] This differed from the way men’s colleges were modeled, multiple buildings around a common.[6] Having everything in one building meant women were under intense supervision.[7] Both Vassar and Wellesley applied the seminary model to their collegiate educations for women.[8]

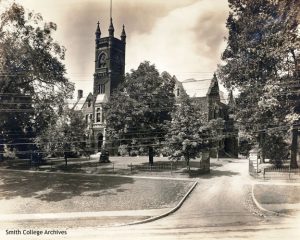

When John M Greene worked to found Smith College, he made his distaste for the seminary model clear. He believed that because women at Mount Holyoke had been isolated, they left school not ready for family life as a wife and mother and had “affected, unsocial, visionary notions.”[9] As such, Smith College diverged from the previous models for women’s colleges. Students lived in multiple buildings, “cottages,” and embedded students in life beyond the college.[10] This is not to say that Greene did not want to control or limit women’s experiences in college, he valued preparing women to become mothers and wives.[11] And so, when students first entered Smith College, they lived in Dewey House with a woman who was in charge of the students and a female faculty member.[12] As Horowitz points out, “Place students under family government as members of the town and prevent the great harm of the seminary—the creation of a separate women’s culture with its dangerous emotional attachments, its visionary schemes, and its strong-minded stance to the world.”[13] But, students still created their own traditions within the college, such as secret societies.

Footnotes

[1] “History & Tradition,” Smith College, accessed April 22, 2022, https://www.smith.edu/topics/history-tradition.

[2] Smith College. “Sophia Smith.” Accessed April 24, 2022. https://www.smith.edu/about-smith/smith-history/sophia-smith.

[3] Helen Lefknowitz Horowitz, Alma Mater: Design and Experience in the Women’s Colleges from Their Nineteenth Century Beginnings to the 1930s, 2nd ed. (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1993), 70.

[4] Horowitz, Alma Mater, 69.

[5] Horowitz, Alma Mater, 3-4.

[6] Horowitz, Alma Mater, 3.

[7] Horowitz, Alma Mater, 4.

[8] Horowitz, Alma Mater, 4-5.

[9] Horowitz, Alma Mater, 71.

[10] Horowitz, Alma Mater, 71.

[11] Horowitz, Alma Mater, 71.

[12] Horowitz, Alma Mater, 78.

[13] Horowitz, Alma Mater, 75.

Further Research

Sarah H. Gordon, “Smith College Students: The First Ten Classes, 1879-1888.” History of Education Quarterly 15, no. 2 (1975): 147–67. https://doi.org/10.2307/367978.