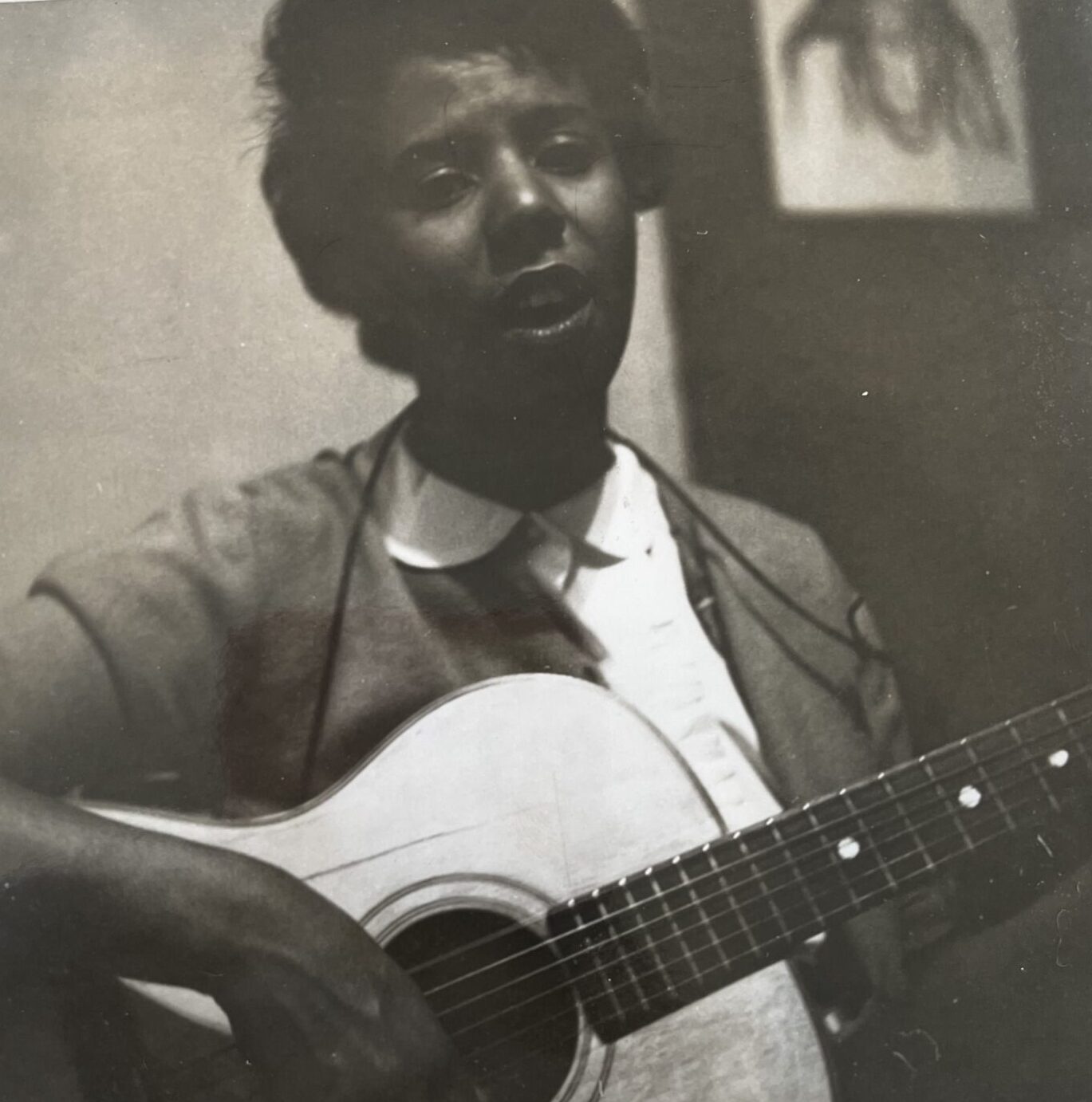

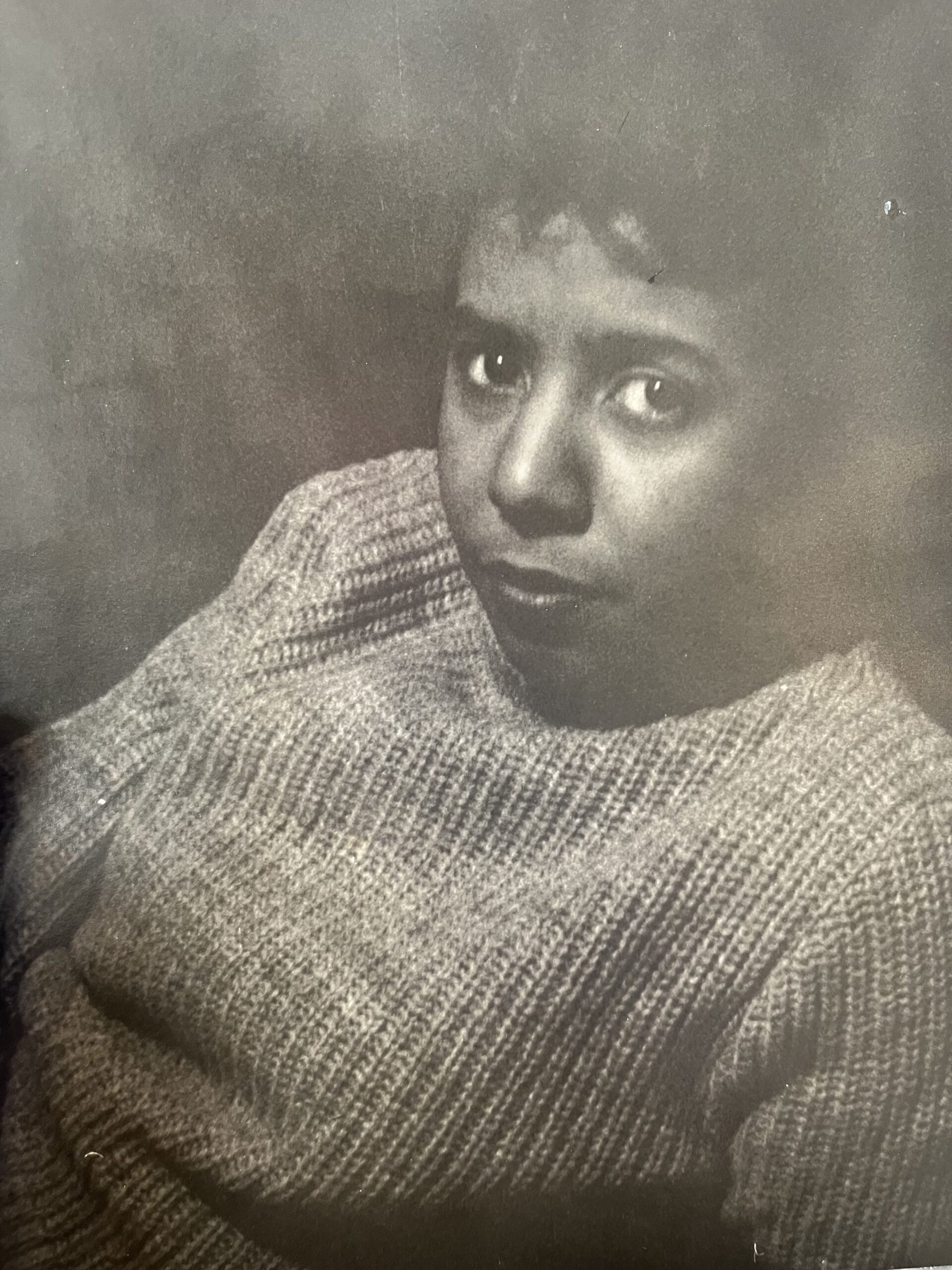

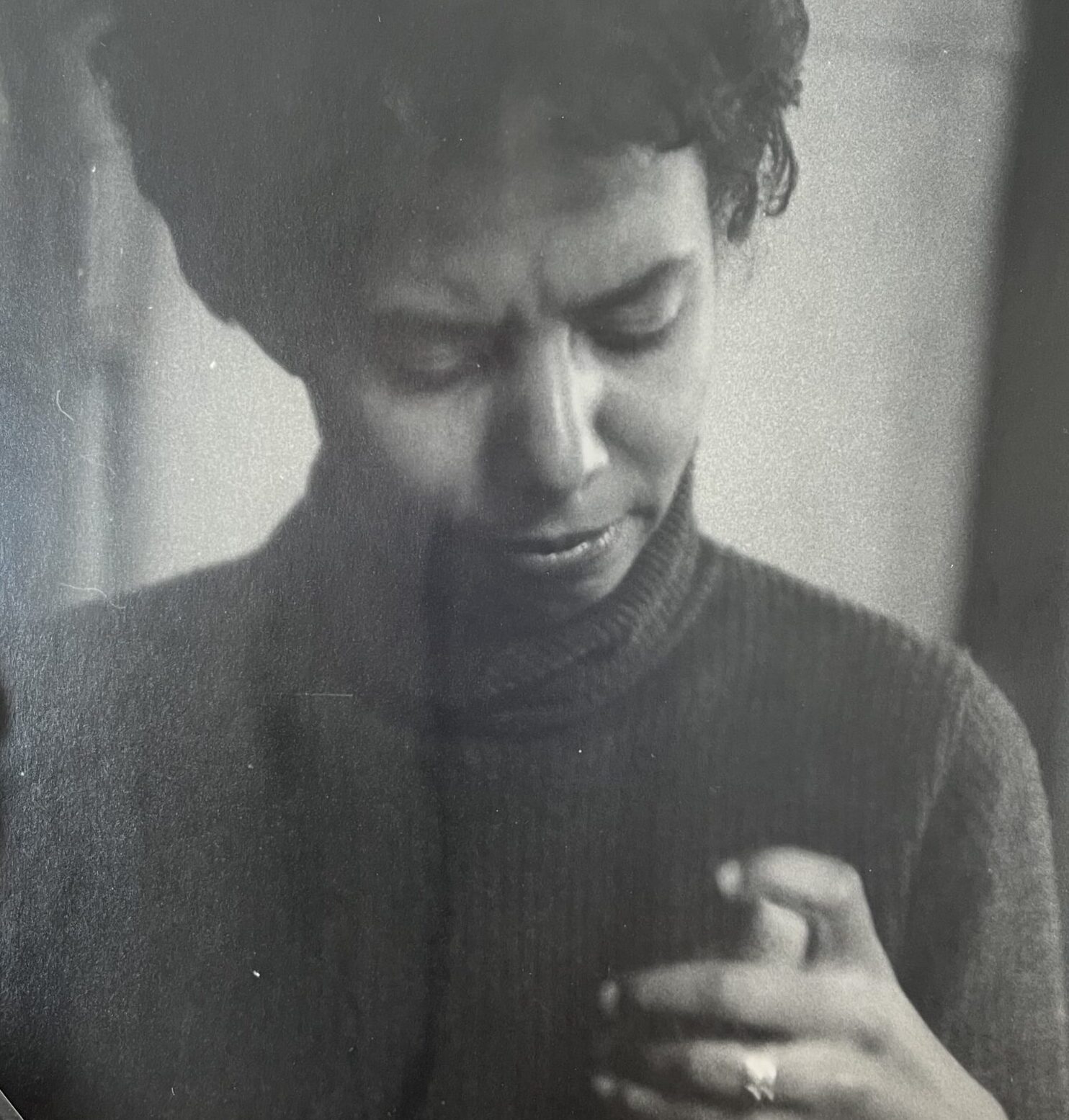

Greenwich Village, 1957. Lorraine Hansberry is writing A Raisin in the Sun, which will soon become the first play written by a Black woman to be performed on Broadway — she is 27 years old, separating from her husband, and teetering on the brink of stardom. Molly Malone Cook is taking photos. Photos of chess players in Washington Square, of boys with telescopes— and of Lorraine. [1]

It would take countless empty museums to display all that we don’t know about hidden (and erased) queer love. There’s no record of exactly when Lorraine and Mary met, or where. 1957, sure, but during spring or autumn? Missing too is when their brief love affair ended. By the time Lorraine was attending the premieres of A Raisin in the Sun in 1959, Molly Malone Cook was in Provincetown, opening a photography gallery and beginning a life with poet Mary Oliver. Oliver would later write about a relationship Molly had before her, possibly referring to Lorraine:

“I believe she loved totally and was loved totally. I know about it, and I am glad…I only mean to say that this love, and the ensuing emptiness of its ending, changed her. Of such events we are always changed- not necessarily badly, but changed. Who doesn’t know this doesn’t know much.” [2] .

Like many mid-century lesbian relationships, we do not know much about Molly and Lorraine’s love.

Unlike many mid-century lesbian relationships, we have photographs.

In her biography of Hansberry, Imani Perry explores Molly’s photographs of Lorraine, writing that:

“…photos are different from all the others and tell a story in and of themselves. In them, Lorraine does not have her race-woman armor on as she usually does. Nor is she posed. She is casual, tomboyish. Her hair is mussed. Her back curved, adolescent, languorous, and playful at once. The light and wonder that we know must have often been in her eyes, because of her wicked humor and deep curiosity, I have seen only Molly capture on camera. The images are a dance of love.” [3]

Molly was an avid photographer, one of the first employed by the Village Voice. [4] In these photographs, Lorraine is not stifled, nor a posing muse — she is mid-laugh, mid-thought, mid-song. We can imagine them not just as photographer and subject, artist and muse, but as equals — lover and lover.

A Note on Deferral

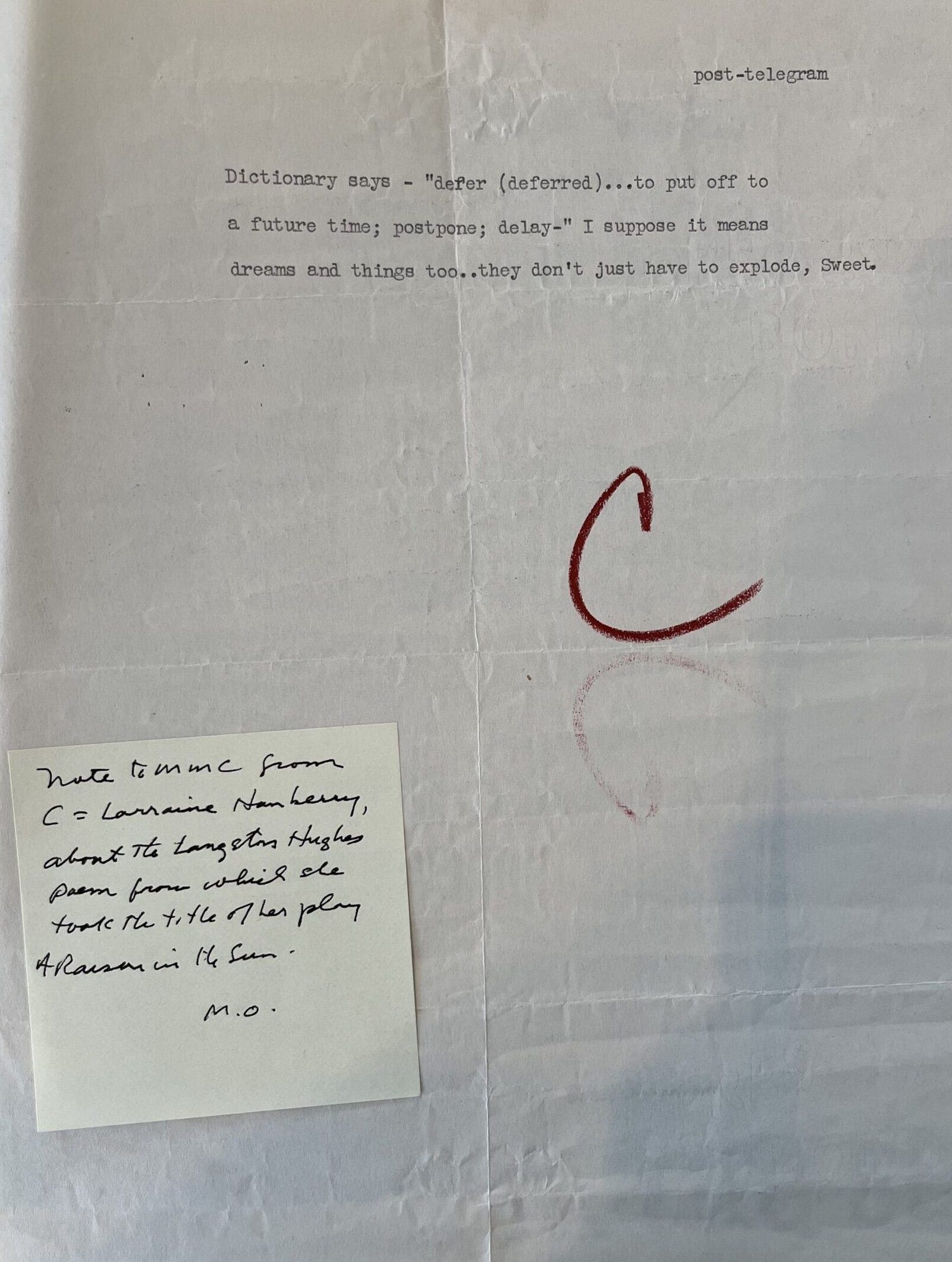

In an undated telegram, Lorraine Hansberry writes to Molly Malone Cook, discussing the Langston Hughes poem from which she’d borrow a line to name her play [5] — A Raisin in the Sun.

“Dictionary says — “defer (deferred)…to put off to a future time; postpone; delay—” I suppose it means dreams and things too…they don’t just have to explode, Sweet.” – C

The idea of deferral is integral to understanding Lorraine’s identity as a Black lesbian woman; in her analysis of a documentary about Lorraine Hansberry, Jennifer DeClue writes that “the concept and problematics of deferral not only punctuate the narrative of A Raisin in the Sun but hug the contours of Hansberry’s life as an activist, outline the closeted confines of her sexual desire, and concretize with the impact of her untimely death.” [6]

Notably, Lorraine does not sign this note to her lesbian love with her name, but rather an initial that is not her own: C. Her ability to live as an out and known queer person is deferred.

But even if Lorraine could not live publicly as a lesbian, this does not mean she deferred loving — nor does it mean that sexuality was not an important part of her life.

Indeed, this note evidences that Molly (or, “Sweet”) was an important part of her intellectual life, and it also suggests that she was actively thinking about sexuality and intersectionality while working on A Raisin in the Sun. Hansberry’s husband would later say, after Hansberry’s death, that her lesbianism was “not a peripheral or causal part of her life but contributed significantly on many levels to the sensitivity and complexity of her view on human beings and of the world.” 7]

The concept of (forced) deferral also turns the photographs Molly Malone Cook took into active actions of resistance. Of insisting we are here. Of refusing to postpone by capturing the present.

The Art — and Power — Of Looking

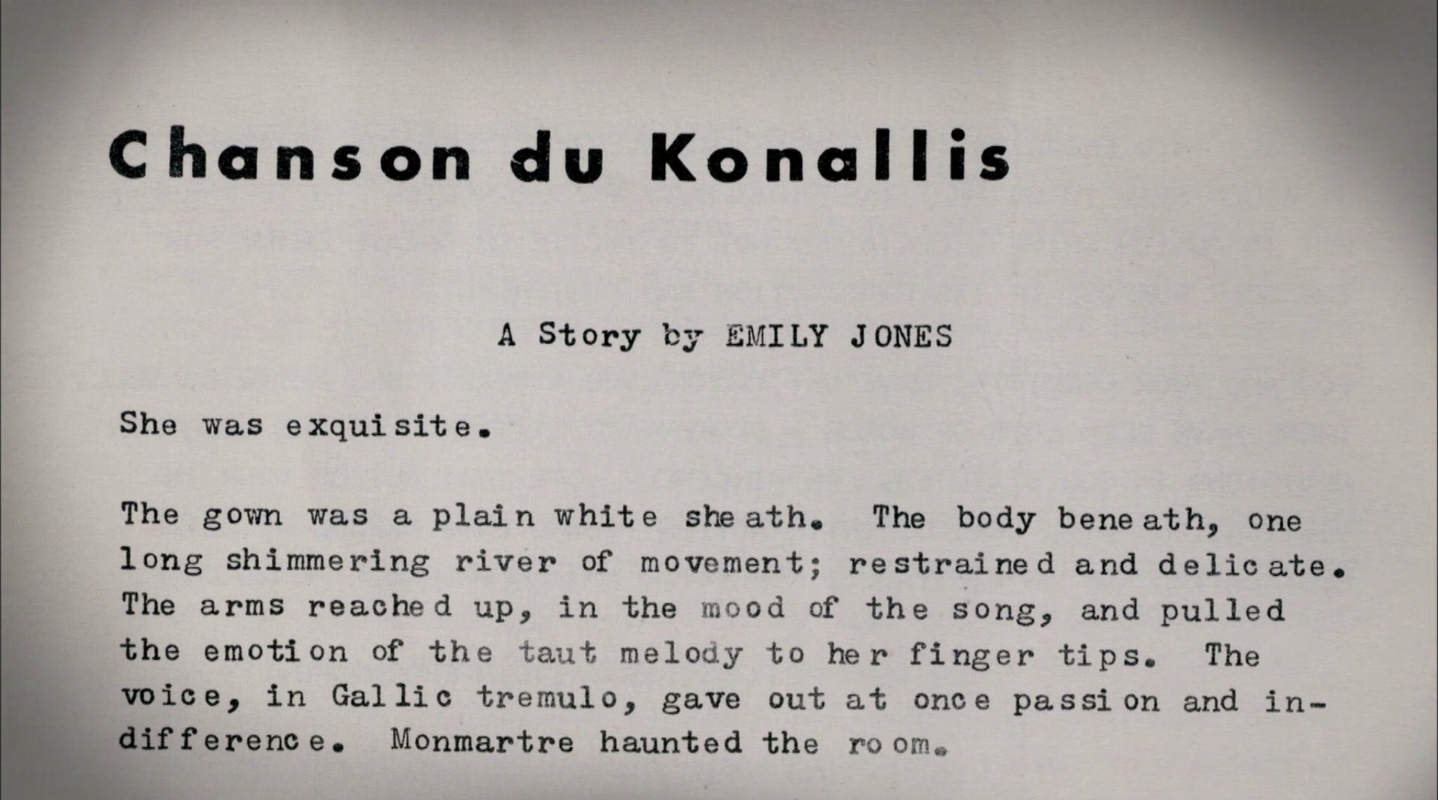

In the late 1950s, Lorraine wrote short stories for gay magazine One and lesbian publication The Ladder under a pseudonym, “Emily Jones.”[8] Her stories explore, among other themes, the thrills and dangers of “looking” for lesbians — the pleasure of looking at another woman and the terrifying nature of being seen for who you are. Unlike Lorraine’s other works, these short stories predominantly feature white characters, perhaps a reflection — and a critique — of who was allowed to be a ‘visible’ lesbian.

In Chanson du Konallis, published in The Ladder, 1958, her narrator remarks, “What a strange moment. It had happened before in life. On the street; parties; in classes in school years back; the thing of being surrounded by many people and suddenly finding another girl’s or woman’s eyes, commanding one, holding one’s own. It was extraordinary. Pleasant, she thought. No, not pleasant. Terrifying because of the kind of pleasure it brought.”[9]

The politics of looking are alive and well not only in Lorraine’s prose, but in photographs of her.

We are looking at Molly looking at Lorraine (a lover looking at a lover), and Lorraine is looking at us. What is Lorraine seeing, behind the camera? After Molly passed away, Mary Oliver would write that her favorite photo of Molly “demonstrates so well that straight-on, clear-eyed look that Molly gave you. When she looked at you, you knew you were truly and deeply seen!”[10]

In looking at these pictures, we might also ask: what isn’t pictured? For example, DeClue writes in her analysis that though photos and film show that “Hansberry was surrounded by white lesbians…Was Baldwin not a part of her Black gay community? Did she know Audre Lorde?” [11] (Audre Lorde would later write about the influence Hansberry had on her, noting, “When you see the plays and read the words of Lorraine Hansberry, you are reading the words of a woman who loved women deeply.”) [12]

At a crucial moment in Lorraine’s story, her narrator decides to hold her gaze with the beautiful woman who is looking at her. [13] She writes, “She did not drop her eyes this time, Why should she? There was pleasure in the looking, she thought suddenly, wildly, yes, she would look right back at her! And she did.”

This World

Lorraine Hansberry’s radical and vibrant life ended far too soon; she passed away at the age of 34 after having pancreatic cancer.[14]

In a journal entry, Molly writes about turning on the TV and seeing a woman she used to know. She does not name this person, but it is possible to imagine that this is Lorraine: [15]

“It was wild. Her voice. I couldn’t replay it. She spoke only a few words. It was mind-boggling. I wonder if I shall ever be able to come back to listen and watch her again…Well I never thought I would see her again — knew I would never hear her voice again in this world.

Oh, I did always think I would see her again and hear her voice again,

but not in this world.”

.

Further Research

To learn more, you can explore:

- The Molly Malone Cook papers at the Sophia Smith Collection of Women’s History at Smith College

- The Lorraine Hansberry Papers at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

- Lorraine Hansberry’s Greenwich Village residence, from the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project

[2] Cook, Molly Malone, and Mary Oliver. Our World. Beacon Press, 2009.

[7] Harris, Elise. “The Double Life of Lorraine Hansberry.” Out Magazine, September 1999.

[9] Hansberry, Lorraine. “Chanson du Konallis.” The Ladder, 1958.

[13] Hansberry, Lorraine. “Chanson du Konallis.” The Ladder, 1958.

[15] Cook, Molly Malone, and Mary Oliver. Our World. Beacon Press, 2009.