From Philosophy to Practice: A Conversation with Lynn Newdome from the Dzogchen Community Center on how to Find Peace

By Radha Consiglio and Aisling Kelly

Dzogchen Center in Conway, MA. Shrine Room.

Can philosophy become an embodied experience? We find ourselves driving on a sunny Massachusetts day in search of the Dzogchen Community located in Conway, eager to get some insight on this very question. We arrive early for our meeting with Lynn Newdome, who has been practicing Buddha Dharma for almost fifty years now, and are quietly welcomed into a richly colorful room full of space to move, where a group of practitioners (including Lynn) participate in a Vajra dance class.

For about twenty minutes, the ensemble learns melodic chants and swift movements atop a colorful circle on the floor by continued repetition. Later, Lynn explains that the Mandala’s different colors (blue, green, red, yellow, and white) can represent various Buddhism ideals, such as humility, vitality, openness, and strength. With every step, the dancers pay their respect to the Earth, as well as one another, in order to move together. The execution of sound and movement in harmony, according to Lynn, is important for aligning the mind, body, and voice.

Mandala in the Dzogchen Community Shrine Room

After wrapping up, Lynn takes us on a tour around the shrine room and the rest of the center. The bright colors of the walls and floors give the center a light and playful atmosphere. Where the shrine is located, Lynn shows us a picture of the center’s late teacher, Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, whose death eight years ago has left the center struggling to continue furthering the practice, in accordance with traditional Dzogchen lineage. The Mahāyāna tradition that came from India to Tibet comprises two principal schools of thought. The Yogācāra perspective (mind-only-view), centers the mind in its perspective, focusing on subjective experience. Madhyamaka (“the middle way”), on the other hand, focuses on objectivity, emphasizing emptiness of mind. In an effort to understand a little more about Dzogchen theory, we ask Lynn if she can give us some insight on how her practice incorporates these views. We sat down in the Tsegyalgar Center’s library to talk about the Center, its practice, and how that practice is grounded in these Indian and Buddhist philosophical schools.

Dzogchen Community Center Library

Dzogchen Community Center Library

The interview begins with Lynn telling us about the origins of her practice. Being raised in a conservative Christian household in Ohio, Lynn was never exposed to any spiritual traditions outside her own. This changed, however, when she attended college. Lynn describes a feeling of groundlessness she felt as a college student, which led her to search for spiritual practices that would help her find a sense of home:“I started being interested in something more than… this cycle of always having to achieve, and rest, and doing it again and again”. Although Lynn came to the path hoping to find an escape from life’s suffering, she soon discovered that the path is less glamorous than one would hope: “My first impulse was all ‘cool, spiritual traditions like sufey dancing, astral travel…I thought I was getting into something really esoteric…” While she initially hoped for mystical effects of meditation, Lynn discovered that Buddha Dharma is a process of evolution that calls us to face the very things we seek to escape.

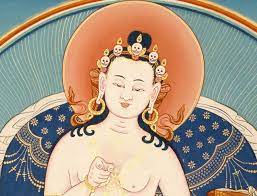

Image of Garab Dorje pointing at the viewer, symbolizing Dzogchen’s traditional “direct introduction” to the practice between master and student (encouraging accountability)

In our class, we’ve focused on two main “schools of thought” within Buddhist philosophy. The Yogācāra perspective (mind-only-view), centers the mind in its perspective, focusing on subjective experience. Madhyamaka (“the middle way”), on the other hand, focuses on objectivity, emphasizing emptiness of mind. In an effort to understand a little more about Dzogchen theory, we ask Lynn if she can give us some insight on how her practice incorporates these views.

Due to the traditional “direct introduction” methodology of how the Dzogchen tradition is passed down, Lynn explains that her center has faced increasing challenges over the past eight years, due to the passing of their meditation master. Lynn explains how the absence of this teacher has delayed “the third turning of the wheel”, which involves gaining insight into the nature of mind through direct teaching. Without this guidance, the center feels lost. Lynn’s description of the impact of her teacher’s passing has allowed us to reflect on the inhibitory and exclusive aspect of the traditional male monastic lineage, calling into question how Buddhist philosophy and practice might look different if women held a more prominent role in its formation.

Knowing that we are here for academic purposes, Lynn encourages us to tighten the grip on the scrupulous “views” we’ve been hearing about in class. According to her, the formation of each school is simply a result of practitioners throughout time deepening their experiential knowledge and holding onto certain “views” about said experiences. Lynn, however, is resistant to this fixation on concepts such as egolessness and emptiness- she wonders if sometimes people can be so fixated on conceptual emptiness that they mistake it to mean void, forgetting that the emptiness of objects is more centered around dependent origination and the connectivity between all things, as opposed to nothingness. Again. she reminds us, the teachings are about more than just concepts- they’re about opening up to these experiences first-hand.

Tibetan Wheel Of life: Lynn points to much of Buddhist symbolism as representing mental states.

Tibetan Wheel Of life: Lynn points to much of Buddhist symbolism as representing mental states.

Nonetheless, Lynn expresses gratitude for the direction that studying philosophy has given her, describing how a lot of the symbolism has aided her self discovery: “I learned that the symbolism wasn’t pointing at anything other than my own mind”. In our interpretation of her current philosophy, it seems that Lynn is pointing to a fuller perception of emptiness through her Dzochen practice- one that can go “beyond emptiness” and acknowledge that the universe is “full of energy”. When asked about the emptiness of mind, Lynn describes the mind as open- anything we learn, we can always go past – even emptiness. There is a certain expansiveness to her philosophy of mind that we really admire.

It is not an easy journey, Lynn reminds us; facing our inner demons can be challenging and painful. In response to our theoretical questions, she smiles: “You are never going to think yourself into Enlightenment. It is said, even the tongue of the Buddha couldn’t explain this.” As Lynn describes the evolution of her practice, she explains that Buddha Dharma (as she prefers to call it) is more experimental than conceptual. Learning to sit with one’s range of experience over time is what allows for a deeper exploration of the mind. As we practice meditation, we learn to observe the way we react to various phenomena in our lives, and be in tune with the emotions they trigger, rather than be governed by them. Thus, while it is clear that philosophy has the ability to open one’s mind to a fuller version of human experience, it is only through this practice of self-discovery and evolution that mere concepts such as selflessness, emptiness, and interdependence can become embodied experiences.