I: Practice Meets Philosophy

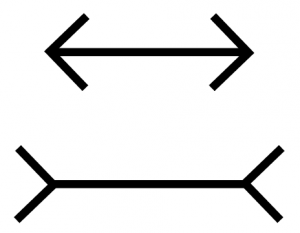

We’ll begin with an optical illusion. Have a quick look at the image below. You’ll see two lines, the first line with pointed arrows on each end and second line with inverted arrows. You might notice that the bottom one will appear longer than the one on top. Now take your two index fingers and place them parallel to each other where the arrows meet the two lines. What do you notice?

You guessed right. The two lines are in fact the same length, the arrows fooling your eyes into seeing something that’s not real. Even now that you know what’s behind the magic trick, your view of the lines doesn’t change. To do that–to perceive the lines as having equal lengths– you’d have to erase the two sets of arrows altogether.

This is the Müller-Lyer illusion, an example that is useful in explaining the difference between understanding Buddhist philosophy academically and realizing its principles in your life through practice. Completing this last step–equivalent to erasing the arrows from the two lines–you see our reality for what it is; a world of impermanence and volatility to which we attach meaning, leading in turn to suffering as we desire and are repulsed by various phenomena.

Here’s an example. You’re watching TV and see an ad for a new car. During the clip, there are two people having a great time road tripping across Utah, and it’s all because they bought the latest model. The car looks like a lot of fun, so you purchase it. It might excite you at first, but you’ll probably find after a while that this initial feeling wears off. You drive to work, you pick up groceries … your experience is nothing like what was promised in the advertisement.

The use of illusion in this ad takes advantage of our cyclic attraction and aversion through appealing to our desire for happiness or close relationships. The road trip you saw was fabricated using a cast and crew, music, and flashy editing, making it appear as a genuine experience. Unfortunately, it’s exactly the same as seeing a longer line in the Müller-Lyer example; even if you know that the couple in the car are paid actors, it still might evoke an emotional reaction.

The lesson here is that we are attracted by what we don’t have, (or averse to our lives without it), and seek more, believing that it will fulfill us. Buddhists see this cycle to be a root cause of suffering. Attaching value to temporary things will inevitably lead to sadness when they disappear; thus, one of the principal aims of the Eightfold Path is to liberate beings from attachment, recognizing the reality of impermanence.

II: What We’ve Been Working On

Our project aims to explore the ways in which philosophical concepts such as dependent origination influence Buddhist practice and, by extension, how they can manifest within our everyday lives. Over the past few weeks, we’ve been practicing with the Green River Zen Center in Deerfield, MA, which belongs to a Zen Buddhist lineage. Through attending sessions and interviewing two sangha members for this podcast, we’ve gained some insight into how silent and walking meditation, sutra recitation, and other rituals work to cultivate what Buddhists call “right view”. We were especially moved by the sangha’s recitation of poems, which we’ve linked here; we encourage readers to take a look at The Song of Jewel Mirror Samadhi and the Identity of Relative and Absolute.

The Zen lineage of Green River places emphasis on the fact that we exist already in a state of interdependence and are all in the process of awakening. Returning to the Müller-Lyer illusion, the truth of human existence is equivalent to the two lines being the same despite appearing otherwise; it’s our obstructed thinking that keeps us from seeing what’s right in front of us. Since normal or “conditioned” perception makes us believe that we exist independently of other people and phenomena, which is a fundamental illusion, Zen practice aims to break down obstructive barriers that conceal our true nature. This realization is nirvana, the cultivation of our capacity to experience reality as interdependent.

Finally, the Zen Peacemakers lineage places emphasis on the ethics of interdependence. Simply put, if our actions affect those around us and vice versa, we all have power to both create and end suffering. Through meditation, which is personally transformational, and vowing to do no harm, Buddhist practitioners lead by example. Internal peace with the world translates through one’s actions, radiating outward and affecting others in a positive way.

We hope that by listening to our podcast, you’ll come away with a few practical tools to utilize in your life as distressful feelings arise. A Green River sangha member advised to always return to the breath, inhaling, then counting on the exhale; you can go up to ten, then begin again. With practice, we’ve seen how a calm mind becomes second nature, and care for sentient beings like breathing.

Kate Bernklau-Halvor + Maya Pemble

Visit the Green River Zen Center Website

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Featured Image Source:

Shiken Seidō (Japanese, 1486–1581), calligraphy by Ekkei Reikaku (Japanese, d. 1609). Sparrows and Bamboo. https://jstor.org/stable/community.24628486. <a href=”http://www.clevelandart.org/”>The Cleveland Museum of Art</a>;Cleveland, Ohio, USA;Collection: ASIAN – Hanging scroll;Department: Japanese Art;Gift from the Collection of George Gund III. Accessed 29 Apr. 2022.