(I know this seems like the set up for a joke, but bear with me – it’s an honest question which yields surprising takeaways).

Kwame Anthony Appiah recently gave a lecture in Smith College’s cavernous Carroll Room that answers this baffling question. It was a full house – the kind of crowd you’d expect to see at a rock concert, not a philosophy lecture. When Appiah started speaking it quickly became clear that he had enough star power to warrant this sort of hype. He stepped up to the podium and launched right into an anecdote about the inscrutability of his own identity as a mixed-race man. He jested with the crowd about the way taxi drivers often try to assess where he comes from – Belgium? India? Ethiopia? He has been greeted in both Portugeuse and Hindi, causing confusion when he’s incapable of responding in kind. The guesses shift depending on where he is and who the driver is. His real answer to the question “Where are you from?” – London – is often unsatisfying to these drivers. Appiah knows they’re really trying to ascertain where his family originally comes from. They’re wondering, “What are you?”

Appiah asks: why do identities matter? Why do the taxi drivers care? (And he, unlike many, will maintain that identities matter). Every identity, Appiah notes, comes with labels and with some idea what it is about a person, whether it be practices or appearance, that would make it appropriate for them to be categorized under that label. We use labels to understand people. Our identities might give people a reason to hate us, love us, or think that they’re better than us.

But labels aren’t just things that are applied to us by taxi drivers and other strangers; they’re things we willingly use to describe ourselves. Identity matters to people, to their understandings of themselves. Having a word to identify with can help us understand how we fit into the world and lend us a sense of belonging. Identity can also give us our reasons for doing things. A person who is raised Catholic may go to confession. If you were to ask them their reason for doing it they might simply answer that they are Catholic. Our identities come with these attendant habits and moral attitudes which help lend reasons to our lives.

But people who share identities don’t always agree on which practices and beliefs are necessary criteria for admission into the group, debating things like whether you can be Catholic without ever attending Mass. Despite the common understandings we have of certain labels, the individuals who make up any group are varied and believe different things.

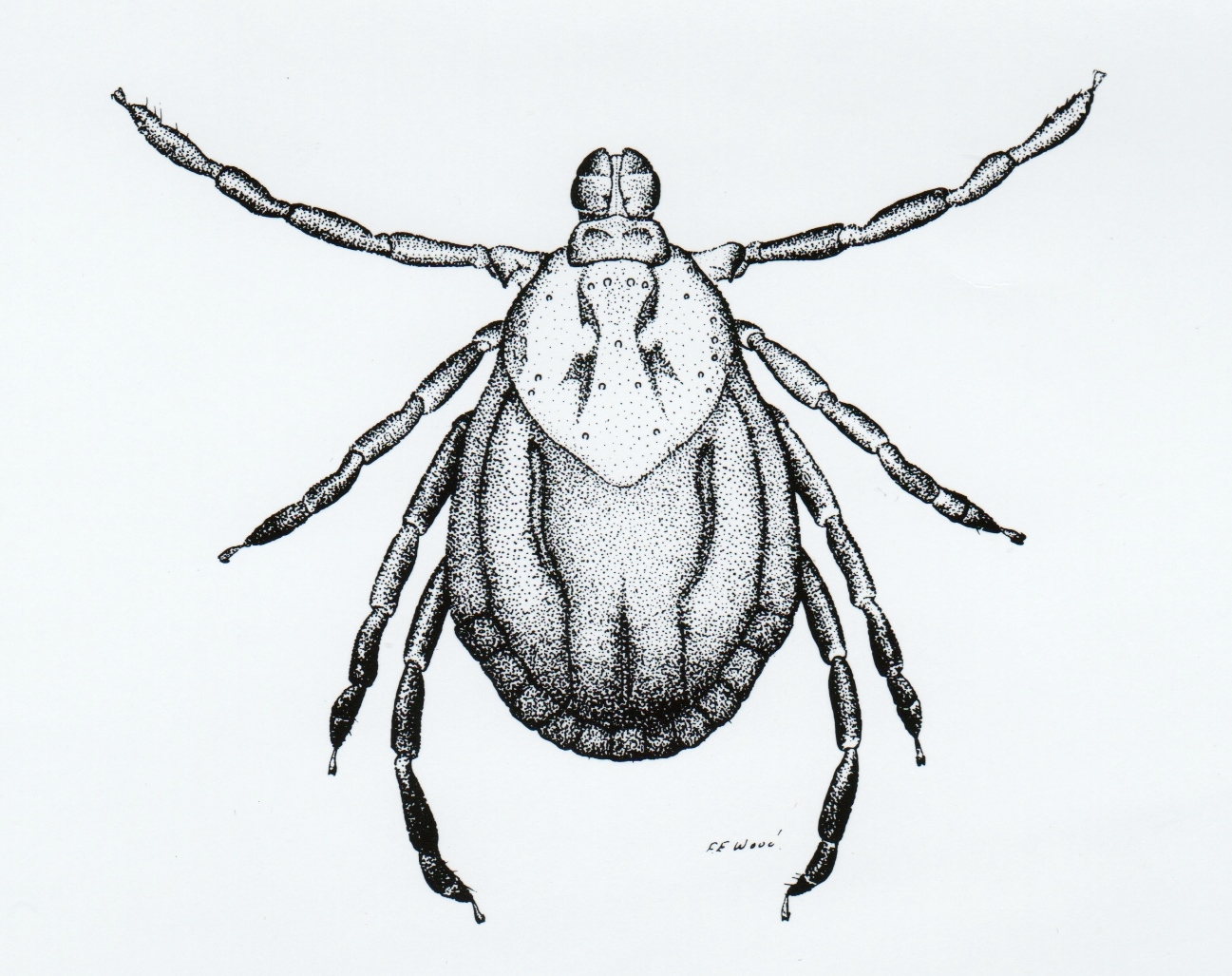

This brings us to tick bites. Mid-talk, Appiah introduced the idea of ‘generics.’ The statement “Tick bites give you Lyme disease” is a prime example. While it’s true that lyme disease is caused by tick bites, it’s not true that all tick bites will give you Lyme disease; in fact, only 2% of tick bites transmit it. Generics like this may be true but they lack specificity, being, well, generic. They can be very misleading. Appiah notes that we often make similarly generic statements about groups of people.

Appiah warns us that taking identity to signify beliefs precludes the possibility of cooperation between people with differing identities. He sees this clearly demonstrated by the state of partisan politics in the United States. If we know someone’s party we presume to know what they will say about everything – from guns to healthcare – before they even say it. But, there are people across the aisle who agree with us, just as there are a number of ticks whose bites do not transmit Lyme disease (and a number of Catholics who don’t go to Mass).

So what is Appiah’s solution to the divisive nature of partisan politics? It’s simple – talking. He believes that we need to be around each other, not just in political spaces, but also at the kids’ soccer practice and the block party. We need to get to know and care about people who hold different beliefs, and be in conversation with them. We don’t have to agree or change each others’ minds, we need to find ways to live together anyway.

Although I tend to agree with Appiah’s argument on the whole I can’t help but feel wary about his relentless optimism on the power of conversation. While I can, and unfortunately do, talk to my homophobic family, I don’t know if I can trust them to have my best interests at heart if they aren’t going to change their minds. What use is their kindness towards me if they advocate for laws that harm people like me?