In our current political climate, the word “identity” has become something of a buzzword. Identity serves as a uniting force for individuals who share some common attribute, such as race or gender, and can be an enormous source of solidarity. But even at progressive institutions like Smith College, identity can sow divisions and create harmful stereotypes. To what extent, then, should we embrace our own identities?

In a public lecture entitled “Identity and Identities,” philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah addressed this question to a packed audience of faculty, students, and members of the community. Upon my arrival, I was surprised that I had to jockey for a seat. The philosophy lectures I usually attend involve just a handful of philosophy majors and professors gathered in a cozy classroom. What made this philosopher so special that he could fill a cavernous event space on a small college campus?

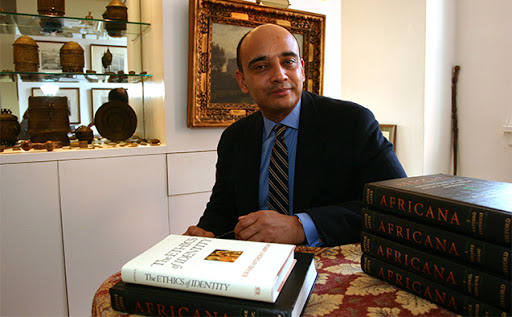

“A brown skin man gets into a cab and speaks with a British accent,” Appiah began. Appiah himself is this brown skin man, and his combination of identities (brown skin and a Downton Abbey-style British accent) often leads cab drivers to do a double take. In the first few minutes of his lecture, Appiah took us on a dizzying ride through his life narrative. We learned that he was born in London to a British mother and Ghanaian father, raised in Ghana, educated in Britain, and currently lives in the United States. It began to dawn on me that this wasn’t an ordinary philosophy lecture. Appiah wanted to emphasize that his personal narrative is central to shaping his views on identity.

Appiah then brought up a Danish newspaper headline he encountered that read: “Can Muslims Be Danish?” I was reminded of the semester I spent studying abroad in Denmark, where my Danish host family would often talk about the need to “integrate” immigrants into Danish society. Is there a way to be authentically Danish? Appiah responded with a resounding no, as his own identities show that there are multiple ways one can belong to an identity group. He does not fit the stereotypical image of a Brit, nor a Ghanaian. But that does not make him any less British or Ghanaian than other Brits and Ghanaians. Appiah rightly stressed that we shouldn’t assume that there is only one way to belong to an identity group.

But how does political identity fit into this picture? Surely political groups are bound by a set of core, unyielding beliefs. Appiah suggested otherwise when he showed us a photo of two Trump supporters wearing t-shirts that read: “I would rather be Russian than a Democrat.” These individuals are so loyal to their party identification, and particularly their identification as Trump supporters, that to them, being Russian would be preferable to crossing the political aisle! I laughed with the rest of the audience at the absurdity of the image, but I also questioned the origins of my own beliefs. It’s a bit alarming that I can’t recall which came first—my political beliefs or my political identity.

The Trump supporter example indicates that political polarization is so widespread that it is impossible to overcome. But Appiah argued that we can overcome these divisions by engaging in mutually respectful interactions with people whose identities differ from our own. For instance, a Republican may be more accepting of a Democrat if she interacts with the Democrat regularly at a soup kitchen they both volunteer at. I wonder, however, how realistic these interactions are. Political identity is closely tied to political views on other aspects of identity such as race, gender, and religion. Can we reasonably expect a transgender individual to build mutual respect with someone who does not support public accommodations for transgender people? I would say no, because the latter person’s views negatively impact the former person’s ability to live comfortably as transgender.

It’s fair to suggest that overcoming personal divisions is a necessary first step toward changing one another’s political views. But Appiah also believes that we must recognize our membership in the global community. This is easy for him to say, as he is about as cosmopolitan as they get. Since his family members span a range of cultural, national, and racial identities, it comes as no surprise that he feels like a citizen of the world. But the harsh reality is that globalization has left vulnerable groups behind economically and has stoked nationalist sentiment around the world. How can we make opponents of globalization feel included in the global community? We need to make globalization work for everyone before we can live in a world of cosmopolitans.

Despite my misgivings, Appiah’s optimism felt refreshing. The title of the lecture, “Identity and Identities,” suggests that we can embrace our own identities while at the same time respecting the many different identities that surround us. Doing so, however, involves the challenge of recognizing our obligations to one another both as members of a democracy and of a global community. Yet perhaps something as simple as everyday conversations can help us get there.