“The Brightest of the Fall Flowers”: Chrysanthe-Mask

“The Brightest of the Fall Flowers”: Chrysanthe-Mask

By Lyn Flores (’24)

Sylvia Plath struggled with her identity in society. She wanted to be “a triple threat woman: writer, wife, and teacher.” However, she also despised the way that being a woman in the 1950s held her back from so many opportunities. Plath constantly had to perform to pass as normal in the world: the gendered requirements in her time suffocated her. In addition to this, Plath was highly ambitious, publishing her first poem at eight, and continuously worrying about her arguably superior academic performance.

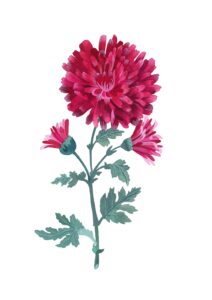

In 1952, Plath worked for the press board at Smith, where it was her job to write a press release about Smith’s annual Mum Show. As an artist, Plath valued the raw reaction that the naturally occurring world of flora could evoke, eliciting emotional responses that no man-made object could ever create. But, this plant was anything but naturally occurring. The long-standing horticultural tradition of chrysanthemums caused the flower to drift incredibly far from its natural state. They have been bred for shows for millennia, prized for their beauty, many varieties no longer able to self-pollinate. The chrysanthemum originally bloomed in early autumn, flowering when the days are short and nights are long. They used to signify joy and beauty despite the oncoming winter, but this becomes meaningless when growers can control the light at any time to yield them. Originally a symbol of hope, mums have morphed to become a show-piece in the eyes of the world.

Plath found herself yet again subjugated to the demands of society in writing about the mum show. If this was her introduction to the plant, what else could she think of them other than a curated enterprise, built to be displayed? The artificially evolved chrysanthemum thus became the perfect symbol to signify her feeling of masking to the world. Truly, “the brightest of the fall flowers” as she described in her press release, has the ability to outshine everything else, and blind the world to anything under its glow.

Plath would later draw on her knowledge of mums in her poetry. The first of Plath’s poems to include chrysanthemums was “Street Song,” written on October 4, 1956. “Street Song” tells the story of a person who is guilty of some sort of horrific act or crime but who was allowed to simply walk free in the world. Plath states this situation is truly a “mad miracle”: it’s absolute insanity that a criminal is walking on streets with the common folk. The guilty purchases “Yellow-casqued chrysanthemums” (Plath 2018: 35) to disguise themself in the public. They serve as “reasonable items” that “ward off…suspicions.” Simply put, the flowers act as a mask in this poem, hiding the true personality of the criminal. Now, because they have chrysanthemums, they can appear beautiful.

The 1960 poem “Leaving Early” also features chrysanthemums. The story follows Plath’s narrator, who is “bored” and unimpressed with another figure in the poem, a lady. What the speaker will remember after leaving is not the woman, but instead the flowers in the room. The speaker goes on describing the menagerie of flowers present and how they are much too suffocating: using descriptors such as “stink of armpits” and “old water thick as fog” (Plath 2018: 145). Essentially, Plath is describing a garden whose artificiality is oppressive.

The most descriptive is that of the chrysanthemum. Plath depicts the mums as “watching” her speaker, judging her just as society does. To Plath, it seems that chrysanthemums are the epitome of what belongs in a curated garden. Furthermore, their display in the mirror is not reality, as they appear twice, illustrating how a chrysanthemum’s appearance has been modified—perhaps mutilated—far beyond how they once naturally appeared. Plath’s narrator has much disdain for this “lady” and her garden, just as Plath herself has much disdain for fake-ness and the fact that she must hide her authentic self. She despises the idea of what this garden represents, and it makes sense she would be “leaving early” from this place where she cannot be herself.

Chrysanthemums are stunning, but their fundamental nature has been permanently altered. Plath learned from her time reporting on the chrysanthemum show, understanding how society viewed the plant and valued it for its looks. She understood how she was expected to describe it. Nevertheless, she used the symbol of the chrysanthemum in her work to convey the problems she had with artificiality. “The brightest of the fall flowers” are definitely alluring, but this does not change the fact they represented something Plath detested.

Works Cited