Literary Contexts for Sylvia Plath’s Use of Orchids

Literary Contexts for Sylvia Plath’s Use of Orchids

By Sarah Kunkemueller (’23)

Content Warning: this post contains references to severe mental illness and sexual themes.

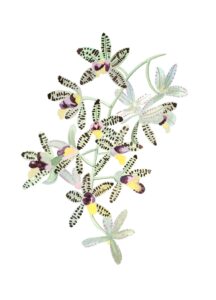

In Sylvia Plath’s poetry, the image of the orchid is traditionally seen as a metaphor for Assia Wevill, the woman with whom Plath’s husband had an affair. Two of her most famous references to orchids come in poems written after her separation in 1962. Orchids derive their name from the Greek word όρχις (órkhis), meaning testicle, and their erotically-shaped bulbs make them easy to associate with adultery (Horvath 2021: 86). However, a broader literary context for orchids hints that perhaps Plath’s use of the flowers had another dimension.

In 19th century England, Victorian society was experiencing an “orchidmania,” during which the exotic shape and properties of orchids had turned them into a luxury bloom. During this widespread obsession, evolutionary theory rose to prominence, inspiring fears that plants were more sentient and human than previously understood. Orchids, especially, seemed to be able to sense human honesty, and failed to propagate in the care of insincere botanists. Rising out of these fears was the Victorian genre of the monstrous plant, including the “vampiric” orchids of H.G. Wells and the creepy flowers of Theodore Roethke’s poem “Orchids” (Chang 2019: 161). Orchids took on a bestial, wild association in Plath’s 1961 poem “The Surgeon at 2 AM” (Plath 2018: 170-1):

Stenches and colors assail me.

This is the lung-tree.

The orchids are splendid. They spot and coil like snakes.

The heart is a red-bell-bloom, in distress.

I am so small

In comparison to these organs!

I worm and hack in a purple wilderness.

These lines depict the orchid as an ailing organ, which writhes and rebels within the body. This poem, which depicts a surgeon replacing the natural landscape of their patient’s body with “pink plastic limb,” is likely inspired by Plath’s own experiences as a patient. After a suicide attempt, Plath experienced improperly administered electroshock therapy, which fundamentally altered her moods and left her as one of the “grey-faced” patients that line the surgeon’s halls in the poem, nameless and unhealed. This context implies that it is Plath’s body on the table, and the orchid one of her organs. But unlike the concrete imagery of the lungs and the heart, the orchid represents an amorphous “purple wilderness.” Here, the orchid is a monstrous invader within the body, but also takes the form of a crucial organ; it represents her mental illness.

After Plath’s separation, however, the orchidian monster began to shift shape in her poetry. The breakdown of her marriage severely affected Plath’s mental health. Wevill appeared in many of her poems as an interloper, sometimes represented as an evil orchid, such as in the 1962 poem “Fever 103°” (Plath 2018: 231):

Hothouse baby in its crib,

The ghastly orchid

Hanging its hanging garden in the air,

Devilish leopard!

Radiation turned it white

And killed it in an hour.

During this poem, inspired by a real fever of Plath’s, her body is rapidly deteriorating. As her fever intensifies, she undergoes a series of rapid transformations—as Plath critic Al Alvarez describes it, “baby becomes the orchid, the spotted orchid the leopard, the beast of prey the adultress; by which time the fever has become a kind of atomic radiation” (Alvarez 1966: 70)—with the orchid overwhelming her body before the nuclear devastation allows her, in the poem’s second half, to reflect more clearly on her relationship with her husband. Wevill, as the “lecher’s kiss” which incited this illness, is represented through the menacing and erotic image of the orchid. Thus, Plath links her internal torment and Wevill’s treachery together through this image. This is consistent with the final representation of the orchid, in the 1962 poem “Burning the Letters” (Plath 2018: 204-5):

And a name with black edges

Wilts at my foot,

Sinuous orchis

In a nest of root-hairs and boredom–

Pale eyes, patent leather gutturals!

Warm rain greases my hair, extinguishes nothing.

In this excerpt, as Plath literally burns her husband’s love poems and letters to Wevill, the flower’s “root hairs and boredom” are an “invagination” of Wevill’s body (Bundtzen 1998: 447). The use of “sinuous” to describe the orchid implies sneakery and malice, but is also very similar to the “sinew” of connective tissue, linking Plath’s body to her husband’s and his lover’s. As she lights the letters, she destroys the physical evidence of their love, harming their romantic connection and improving her emotional state. As she gains control of their written history, she causes the orchid to wilt, representing a personal triumph over both the external and internal monsters the orchid represents.

Works Cited

Alvarez, A. 1966. “Sylvia Plath.” TriQuarterly 7: 65–74.

Bundtzen, Lynda K. 1998. “Poetic Arson and Sylvia Plath’s ‘Burning the Letters.’” Contemporary Literature 39 (3): 434–51.

Chang, Elizabeth. 2019. “The Sentient Specimen Returns.” In Novel Cultivations: Plants in British Literature of the Global Nineteenth Century. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

Horvath, Brooke. 2021. “‘Orchids’: Undomesticating the Greenhouse.” In A Field Guide to the Poetry of Theodore Roethke. William Barillas, ed. Pp. 86-91. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, Swallow Press.

Plath, Sylvia. 2018. The Collected Poems. Reprint edition. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics.