Hedges on the Post-War New England Landscape

Hedges on the Post-War New England Landscape

By Madyson Grant (’25)

Sylvia Plath’s works are often reduced to the framing of her own biography—her dating life, her depression, her suicide. Plath’s work is never offered the opportunity to breathe outside of that space; to be read as critique rather than confessional. “The Moon and the Yew Tree” is a perfect example of this nearsighted reading of Plath’s work. The yew tree, also known as a species from the genus Taxus, from the family Taxaceae, makes three named appearances in Plath’s work. Each time, it is described in reference to her father and usually only thought to be a shallow metaphor—a tree of darkness, looming just like her dad (e.g., see Manners 1996). Approaching Plath’s work through a botanical lens, as a plant commonly found in the tended Massachusetts and England landscapes she lived in, opens up new possibilities for literary criticism. The yew may not refer to her father so much as it does her 1950s horticultural contexts.

The yew presents a symbol of constraint for Plath. Growing up in Wellesley, Massachusetts in the 1940s and 50s, she occupied a post-World War II suburbia with limited botanical range. By that time, the 1942–1945 boom of the wartime victory gardens was on the decline. No longer were people intent on growing fruits and vegetables for the war effort, instead favoring heavily manicured lawns—impenetrable, grass-filled expanses with little to no interspecies plant mingling (Berall 1966; see also Robbins 2007). The only diversity allowed among the suburban landscape was with flowering plants—and even then, most homeowners stuck to the same formula—dahlias, roses, and geraniums, to name a few (Morgan 2022).

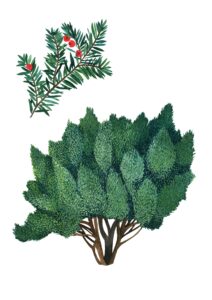

Yews would’ve been among this lineup—not as flowering plants, considering that they are non-flowering gymnosperms—but as hedges in place of the usual 1950s white picket fence. According to University of Missouri plant scientist David Trinklein, the tree best-suited to the New England landscape is an English/Japanese yew cross, first cultivated in the early 1900s in Massachusetts by horticulturist T.D. Hatfield (Trinklein 2020). Plath grew up in Massachusetts as well, in the home state for the most commonly-known landscaping yew, and would’ve seen many yew trees and hedges around her local Wellesley suburbs. Later in life, she also had some outside of her home in Devon, England, the place from which she produced her novel The Bell Jar and some of her most noteworthy poem, including the aforementioned “The Moon and the Yew Tree.”

It’s worth mentioning that the yew featured in her suburban landscape was used as a hedge rather than allowed to grow as a tree: a yew that is regulated and trimmed becomes a hedge. Morton Arboretum Plant Manager Julie Janoski describes how to prune yews in an interview on their horticultural history, “Yews can tolerate frequent shearing with an electric hedge trimmer or shears, making them useful for the geometric hedges that were common in landscape designs of a few decades ago” (Botts 2020). She adds, “They will rebound and put on new growth after shearing, which many evergreens won’t.” The yew, a paragon of immortality—tamed for the suburbs. It’s a cruelty Plath would’ve been aware of each time she returned to the image of the yew in her poetry.

In conversation with the yew tree, Plath’s works become something larger than her father—their critiques are not just relegated to the self’s mourning, but rather also to the oppression of self-identity in post-World War II America, especially in the suburbs. Because of her awareness of both the history of yews and her life growing up with them nearby, she would’ve understood how consistently a housewife must work to tamp down the wild ranging limbs of a yew tree, constantly set to grow past the limits of the hedge. As Janoski describes: “Although yews can be sheared into boxy hedges or geometric shapes, it’s not natural for them. Both the Japanese yew and the English yew will grow into trees 30 or 40 feet tall and wide if they get the chance.” To be confined is unnatural—and Plath, considering her feminist poetry of “Daddy,” “Lady Lazarus,” “Ariel,” and of course The Bell Jar, would identify with this commonplace repression. In the end, the yew becomes not Plath’s father, but Plath herself—hemmed in yet immortal, constantly reaching to grow outside the bounds of the expectations placed upon her.

Works Cited

Berrall, Julia S. 1966. The Garden: An Illustrated History, New York: Viking Press.

Botts, Beth. 2020. “Yew Shrubs, Hardy and Attractive, Are the Stuff of Ancient Legends and a Great Addition to Midwest Yards.” Chicago Tribune, 19 Dec. 2020, https://www.chicagotribune.com/lifestyles/home-and-garden/ct-home-garden-morton-1217-20201219-rjk2cdnchbci7cr5ttx5cirjsi-story.html. Accessed August 27, 2023.

Manners, Marilyn. 1996. “The Doxies of Daughterhood: Plath, Cixous, and the Father.” Comparative Literature 48 (2): 150–71.

Morgan, Jenny. 2022. “The Age of the Atomic Garden: Trends That Shaped Gardens in the 1950s.” North Shore Heritage Preservation Society. August 27, 2022. https://www.northshoreheritage.org/blog/2022/8/16/the-age-of-the-atomic-garden-trends-that-shaped-gardens-in-the-1950s. Accessed August 27, 2023.

Plath, Sylvia. 2005. The Bell Jar. Princeton, NJ: Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

———. 2018. The Collected Poems. Reprint edition. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

Robbins, Paul. 2007. Lawn People: How Grasses, Weeds, and Chemicals Make Us Who We Are. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Trinklein, Peter. 2020. “Yews Add Beauty and Durability to Landscapes (David Trinklein).” Integrated Pest Management, University of Missouri. June 12, 2020. https://ipm.missouri.edu/MEG/2020/6/yews-DT/. Accessed August 27, 2023.