Transcript

[A RECORDING OF DYLAN THOMAS]: Do not go gentle into that good night.

Music begins.

[A RECORDING OF MARY OLIVER]: You do not have to be good.

[A RECORDING OF OCEAN VUONG]: He stood alone in the backyard, so dark the night purpled around him.

[A RECORDING OF FRANNY CHOI]: In the first grade. I asked my mother permission to just go by Frances at school.

[A RECORDING OF RICHARD SIKEN’S POETRY, READ BY ANOTHER VOICE]: Every morning, the maple leaves.

[A RECORDING OF STANLEY KUNITZ]: Summer is late, my heart.

The music, which is grand, swells and then stills.

When I was 16, I got really into poetry. I was writing, reading, and trying my best to figure out what it was about the form that drew me in. At one point, I read a poetry foundation article about enjambment, and that helped me to understand the feeling behind writing poetry, but I still felt like I was missing something.

That same year, I bought a copy of E. E. Cummings’s 100 selected poems. In an effort to hone my craft and learn free verse poetry from one of the best, I pushed myself through the book poem by poem, annotating each one and reading them under my breath. I did that until I got to poem number 18.

A recording of Tessa reading a poem plays. It is kind of far off, staticky, echoey.

[A RECORDING OF TESSA READING]: Nobody loses all the time.

Poem number 18 is “Nobody Loses All the Time”. When I read it all the way through for the first time, I put down my pen and immediately read it again. And again. And…again.

[RECORDING]: I had an uncle named Sol who was a born failure—

There was something about this poem that made me stop.

[RECORDING]: —and nearly everybody said he should have gone into Vaudeville perhaps—

It wasn’t the form that threw me off on its own because I was well used to Cummings’s play with parentheticals and spacing by this point…

[RECORDING]: —Because my uncle Sol could sing McCann he was a diver on Xmas Eve like hell itself—

…and it wasn’t the lack of punctuation. Although that did pose a challenge—

[RECORDING, OVERLAPPING]: which may or may not account for the fact / which may or may not account for the fact / which may or may not account for the fact that my uncle Sol…

Tessa sighs.

I didn’t know how to read it.

The same recording from before starts up again, only this time the poem isn’t being read, and Tessa is trying to navigate the logistics of the situation.

[RECORDING] Okay, let me try that again. Just in one take.

This baffled me. There I was looking at words on a page, words broken into convenient line breaks ever so often, and still—I couldn’t read it.

[RECORDING]: Am I supposed to speed up? Okay. I’m going to do this all in one breath.

When I say I couldn’t read it, I don’t mean that all of a sudden the words unmoored from the page and began floating around.

You know, it was different. Words were coming out of my mouth and they were the right words, and there was no doubt they were being said, but there was something missing behind them. And so, I put down the book. I didn’t read past poem 18—just closed it and walked away. I came across my struggle with this poem again recently, when on FaceTime with a friend, I offered to read my favorite poem to her.

I pulled “Nobody Loses All the Time” up on my computer and started to read it aloud, and quickly ran out of breath. I was ashamed. I realized that even after years of writing poetry, I still wasn’t able to read the poem I’d told everyone was my favorite. Something was still missing.

This changes here, though. Now.

Instrumental guitar, played by Tessa, fades in.

Because I want to know. What is it about reading poetry aloud that’s so different from reading it in your head? And how can I learn to do that well?

It’s easy to read something off a page. Listen to this.

An alternate recording begins to play. It is still TESSA, but she sounds distant and echoey. She recites the first few lines of Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Raven”, yet sounds bored.

That’s reading. I took the words that were on the page and I read them aloud so you could hear them, but what happens when I put emotion behind it?

Rain. A thunder CRASH! Tessa begins to read “The Raven” again, this time with more emotion and feeling to it. The sound is more rich and roy.

What we’re dealing with is, in a way, translation—similar to how Pablo Neruda’s poetry takes on a completely different quality when translated into English from Spanish

[ETTA SINGER, SPEAKING SPANISH]: Toda al noche he dormido contigo junto al mar, en la isla. Salvaje y dulce eras entre el placer y el sueño, entre el fuego y el agua.

[ALEXANDRA ZOOK, SPEAKING ENGLISH]: All night, I have slept with you next to the sea, on the island. Wild and sweet, you were between pleasure and sleep, between fire and water.

When reading a poem aloud, you become a translator, except you’re not conjugating verbs, you’re conjugating emotions. If you’re reading a more contemporary or free-form poem, you have to choose how to convey the feelings brought on by the formatting through your voice.

If you’re reading a well-known, often read poem, you have to figure out what it is about your own reading that makes it worth listening to one more time. Before continuing in my process of learning, I talked to my friends Alexander Zook and Etta Strauss Singer about their thoughts on reading poetry aloud.

[TESSA, RECORDING]: I think we’re fine on decibel levels…

[ALEXANDRA, RECORDING]: Hello?

[ETTA, RECORDING]: I’m Etta and I’m talkingggg…

[TESSA, RECORDING]: Wait, yeah. Talk at the same time.

[ALEXANDRA, ETTA]: (fading in, then out) AAAaaah.

Alexandra has been a poet since she was very young, and recently completed a poetry internship at Perugia Press. Etta, on the other hand, has been a performer and playwright for many years.

I hoped that their differing experiences with performance and poetry might help me to shape my approach.

[ETTA SINGER]: Um, I think one of the most foundational teachings for me in reading other people’s poetry—specifically out loud—is, um, that everyone’s going to read it differently, with things like line breaks, punctuation, and enjambment, like you mentioned.

[ALEXANDRA ZOOK]: Everyone—of course everyone is gonna be reading poetry a little bit differently. But, I think also when, um, reading poetry out loud, I also think about what the author intended the poem to be, and that’s a big thing of—the voice that they’re coming from, the background that they’re coming from, and how that influences their writing and their work. Um, so then adding different voices and adding different perspectives just adds so many more layers to the story of a poem.

[ETTA SINGER]: Mm-hmm. I also love when there’s like online recordings where you can actually hear the author read their poem in their own voice, and even if it’s different than how you would’ve interpreted it, it’s maybe a more authentic version of the poem because it’s from the voice of the writer.

[ALEXANDRA ZOOK]: Yeah, no, it’s always so much more powerful when it’s coming from the author, because they are reading it exactly how they intended it to be.

So, I sought out recordings of E.E. Cummings reading his own work. While I couldn’t find anything for, “Nobody Loses All the Time”, I found a recording of Cummings reading “dying is fine)but Death”.

A recording of E.E. Cummings reading the first lines of his poem crackles to life.

[RECORDED E.E. CUMMINGS]: Dying is fine, but death. Oh baby. I wouldn’t like death…

I noticed that while Cummings gives special consideration to his punctuation, which falls and flows into new lines easily and freely, he sometimes gives a space in between words on the same line the same kind of pause he spares for punctuation, or the distance between lines.

Cummings’ voice surprised me too. Whenever I read his poetry, I imagine a younger man, maybe one with a bit of a warbly voice, like maybe Allen Ginsberg, or maybe I’m confusing Allen Ginsberg for Woody Allen. The point is: Cummings does not sound the way he writes.

His signature open parentheticals can’t be explained by a vocal footnote when he reads aloud. Someone who’s heard the poem might not recognize it if they came face to face with it on paper. While his words dance around the paper, they are anchored vocally. He does not stray and he does not ramble. He knows the beginning and he finds the end. Here’s the issue, though. I am not E.E. Cummings.

Acoustic guitar fades in. The sound is inquisitive.

So…what does this mean?

Yeah, I can study E.E. Cummings. I can try to get as close to his voice as possible. I can try to understand him in the fantasies in his work, the quiet domestic moments. I can track how he twists his words and I can see the spaces and hop over them well enough, but when it comes down to it, I am not him.

There’s no guarantee that I’ll read his poem in the way he wanted it to be read. There’s no way to do it so it’ll be perfect.

The guitar ceases. Silence.

What I’m finding is that the poem isn’t the issue. Neither is the poet. It’s me.

For years, I’ve been obsessed with perfection.

[OTHER RECORDINGS]: /perfection. / perfection.

A difficult high school career proved I couldn’t achieve perfection in the way I was perceived, so I quickly gave up on trying to appease my peers. But I found validation and hope in my academics.

Tessa’s voice overlaps.

If I was an A student—if I did everything on time—if I never skipped a class—if my teachers called on me—if they never asked if things were okay—if my work, even without trying, could be the best, then everything would be fine. Then, I could rest easy. Then, things would be perfect. But that’s not how the world works.

Acoustic guitar, this time more solid and resolute, fades in.

I’m still learning. And growing. And trying my best to make mistakes and fall into them maybe without grace, but then pick myself up with some more. There’s no guarantee that anything I do will ever be the best, or maybe even close to it. But I know one thing. Whatever I do, I can make it my own.

The guitar fades out, and Tessa reading “Nobody Loses All the Time” fades in. This time, she’s got the hang of it.

Nobody loses all the time. I had an uncle named Sol who was a born failure, and nearly everybody said he should have gone into Vaudeville perhaps because my uncle Soul could sing McCann He was a diver on Xmas Eve like hell itself, which may or may not account for the fact that my uncle Sol indulged in that possibly most inexcusable of all, to use a highfalootin phrase, luxuries, that is, or to wit farming and be it needlessly added.

My Uncle Sol’s farm failed because the chickens ate the vegetables, so my uncle Sol had a chicken farm till the skunks ate the chickens when my uncle Sol had a skunk farm, but the skunks got cold and died. So my uncle Sol imitated the skunks in a subtle manner, or by drowning himself in the water tank.

But somebody who’d given my uncle Sol a Victor Victrola and records while he lived, presented to him upon the auspicious occasion of his deceased. A scrumptious, not to mention splendiferous funeral with tall boys and black gloves and flowers and everything. And I remember we all cried like the Missouri when my uncle Sol’s coffin lurched because somebody pressed a button and down went my uncle Sol and started a worm farm.

Guitar fades in again. This time, some humming too.

[TESSA’S VOICE, DISTANT] That was it.

The guitar grows again. The humming continues.

Thank you to Alexandra Zook and Etta Singer for their contributions to this piece. Thank you to my grandmother, Jan Brady, whose recordings were wonderful and instrumental in shaping my idea, but ultimately not used for the final piece. And thank you to E.E. Cummings.

The guitar continues for a bit. Finally, it strikes the low E and stops.

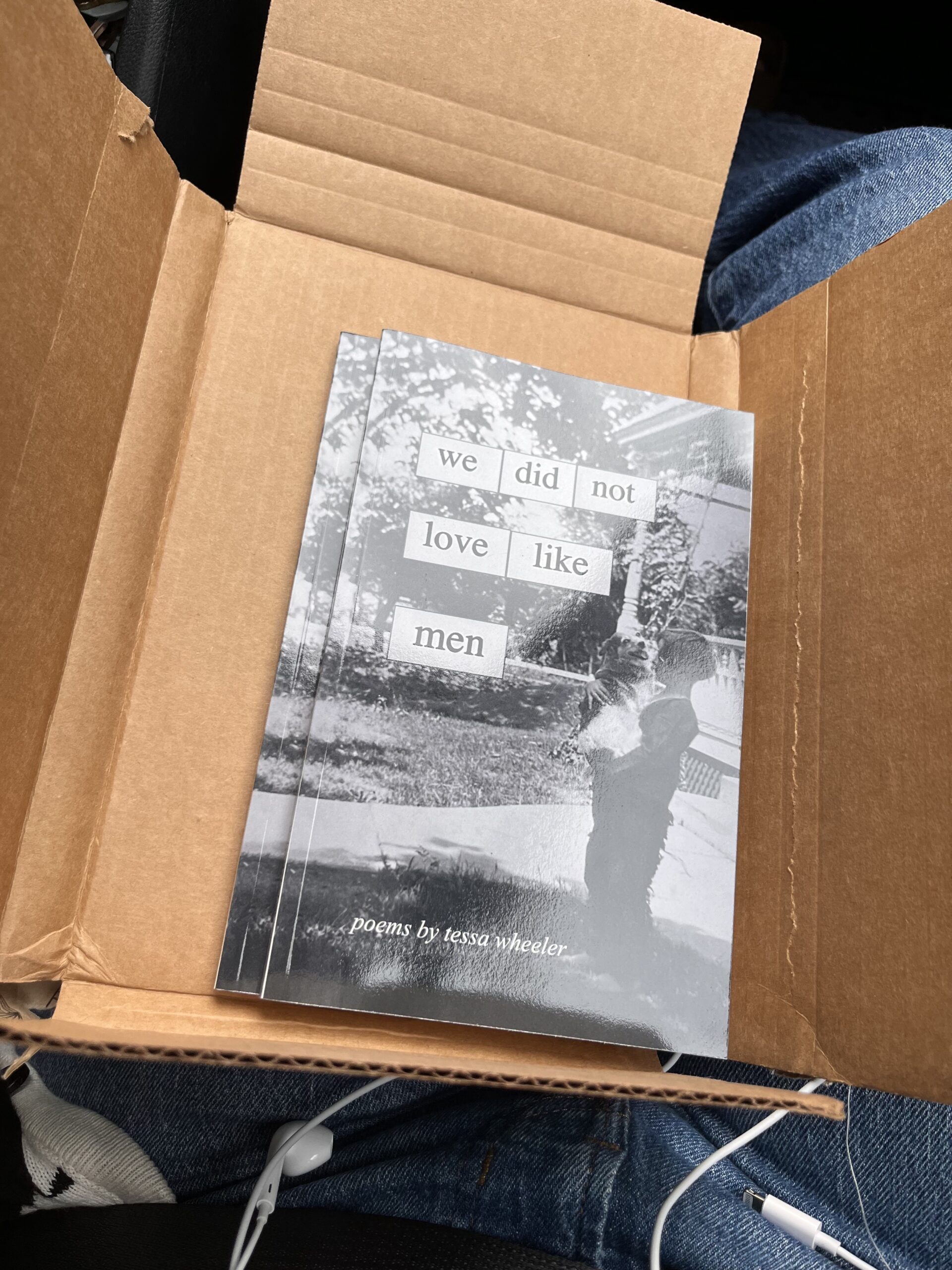

When I was eighteen, I self-published a poetry book. The book, titled “We Did Not Love Like Men”, was a culmination of two years’ work, and chronicled my journey in learning how to write poetry. I started inspired by Siken’s Crush, moved in time to strict left-margin poetry, and then finally found my voice with a marriage of the two previous forms. I reveled in the quiet buzz of writing—the external peace and internal noise. Reading, however, was a different beast to me. Stage fright started to plague me in ninth grade—every time I stepped up to a podium to speak, my voice would be undermined by my shaking, and no matter the solid stance I took, my squared shoulders would quiver under the gaze of even a single audience member. Reading was the great beast to conquer. Writing, in comparison, was easy.

After three years of taking poetry seriously, I decided to challenge myself again and pick up the threads I dropped when I first started learning about poetry at sixteen. This podcast follows me as I try to learn how to read poetry aloud by using E.E. Cummings’ “Nobody Loses All the Time”. The podcast opens with a sonic patchwork quilt of selected lines from famous poets’ work, most read by the poets themselves. Here’s a list of the poets and the poems being read in that introductory part:

- “Do not go gentle into that good night”, Dylan Thomas

- “Wild Geese”, Mary Oliver

- “The Bull”, Ocean Vuong

- “Choi Jeong Min”, Franny Choi

- “Litany in which Certain Things are Crossed Out”, Richard Siken (read by Culumacilinte on YouTube)

- “Touch Me”, Stanley Kunitz

While I explore E.E. Cummings’ work most closely throughout this piece, looking at “Nobody Loses All the Time” and “dying is fine)but Death”, I also nod to Pablo Neruda’s “La Noche en la Isla”, or “Night on the Island”, translated into English by Donald D. Walsh. My friends Etta Singer and Alexandra Zook read the Spanish and then English versions of the poem. I also reference Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Raven” in discussing the importance of imparting emotional weight on words.

The aural landscape of poets reading poems at the beginning is accompanied by a grand synth backing, meant to symbolize the impossible expectations I’ve challenged myself to live up to. Throughout the rest of the piece, music is played by me on an acoustic guitar, with imperfect takes being used. I’m challenging my own ideas of perfection and beauty in this piece, trying to find comfort in the slip-ups that go unnoticed at first.

My grandmother, Jan Brady, recorded herself reading a poem by Theta Burke and, upon my request, sent it in to me to incorporate into my podcast. While I was ultimately unable to keep her recordings in for time reasons, I felt that what she sent shaped the trajectory of my journey within this podcast—that her dedication to getting the best, most perfect recording for me forced me to question what exactly I considered perfection, and if I held myself to a different standard of perfection than I had for other people.

Although this podcast does come to an end, it doesn’t mean my work is over. I will always be working on my writing. I will always be challenging myself to learn and try something new. I will always be looking back at those who came before me, and then casting my gaze forward to ask What can I do?

I will always be learning.

This piece sources audio from YouTube and Freesound. Links to each piece and appropriate credits can be found below.

“Do not go gentle into that good night” read by Dylan Thomas

“Wild Geese” read by Mary Oliver

Ocean Vuong reading “The Bull” for WSJ Style

Franny Choi reading “Choi Jeong Min”

“Litany in which Certain Things are Crossed Out” by Richard Siken and read by another

Freesound attributions:

20sLowThunderRumblewRainSounds by AndOrGraphics — https://freesound.org/s/733679/ — License: Attribution 4.0

Lightning strike by alexdarek — https://freesound.org/s/583742/ — License: Creative Commons 0