Doña Rosa was born in, approximately, 1900 in San Bartolo Coyotepec, Oaxaca, México, She is known for popularizing “barro negro”, with a technique that made the local pottery type, black and shiny after firing in 1953. Barro negro has been a part of traditional craft in the Central Valley of Oaxaca for centuries, dating back to the Zapoteca and Mixteca cultures. Her pieces and techniques quickly gained recognition and became a marker of San Bartolo Coyotepec pottery. Having learned how to make pottery from her parents, Doña Rosa passed down these techniques to her son Valente and, later, to her grandchildren, who continue to dedicate themselves to this profession.

Date unknown, Private collection.

Date unknown, Private collection.

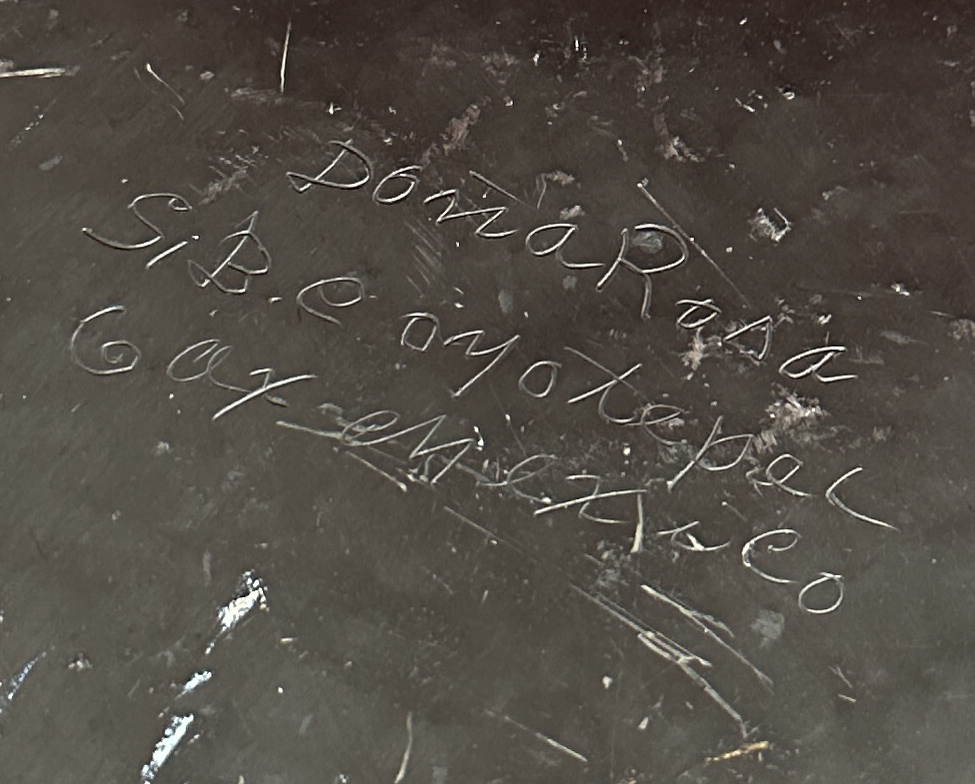

This low dish is a typical example of black pottery, or “barro negro.” It features Doña Rosa’s signature on the bottom, “Doña Rosa S.B. Coyotepec Oax México.” Doña Rosa’s work signals four key ceramic elements which predate Spanish conquest: technique, molding, quartz to polish and shine, and firing. To create such intricate pieces, she would sit on a “petate” (a woven straw mat) next to her wheel which was activated by using a pre-Hispanic method of placing one convex plate upon another, back to back, and spinning them in a manner similar to a potter’s wheel. In addition to using techniques such as pinch potting and coil building, Doña Rosa shaped a variety of everyday objects to decorative pieces. Pieces were fired using an in-ground oven powered by wood, a process which could take eight to ten hours. It was precisely these elements that made Doña Rosa’s pieces stand out in the town of San Bartolo Coyotepec and in the state of Oaxaca.

The endurance of pre-Hispanic practices through colonization, and the growing international interest in her pottery, exemplifies the resilience of Doña Rosa’s practice. Despite international recognition, Doña Rosa remained on her petate, never changing her practice or production style.

This small four-pot piece displays another traditional aspect of barro negro. The decorative piercing and cutting adds contrast to its shiny exterior. This set would have been used as small herb pots to keep near the kitchen, however, several barro negro pieces have gone from being everyday utensils to decorative pieces. The specific burnishing and firing technique makes the pieces fragile over time.

Pictured above are Doña Rosa and her grandson Jorge. Both are making a pot in the exact same technique, molding, and style, with about 40 years difference. The continuing of Doña Rosa’s practice shows how this knowledge and skill are both traditional, contemporary and living. Passing down knowledge is not just about teaching the younger generations, but about fostering a sense of continuity. This process of passing down knowledge is what maintains these traditions. In other words, it preserves the intangible and tangible cultural heritage.

Sources: (Doña Rosa) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WUGMIec4oVs (Jorge de Nieto) https://www.facebook.com/100064834176889/videos/890391911701446

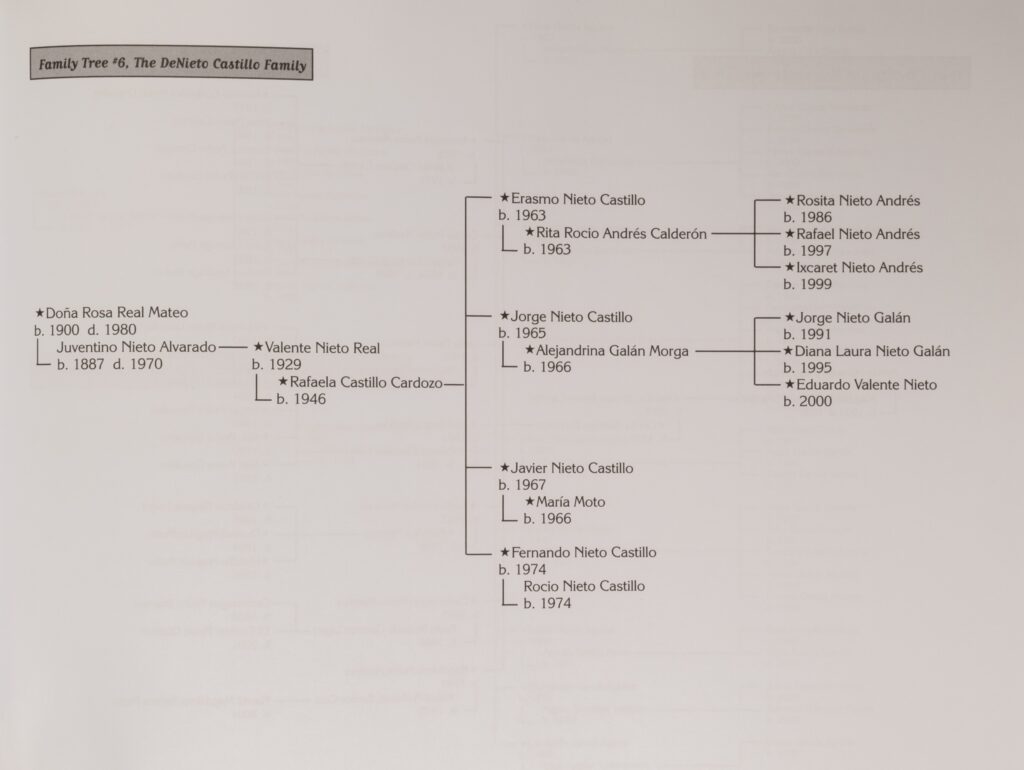

Pictured in the middle is Valente, Doña Rosa’s only son. Valente began working with his mother and father at the age of 11. Since then, Don Valente prides himself on preserving the fundamentals of his mother’s work. Don Valente and his wife, Doña Rafaela, have continued Doña Rosa’s legacy and passed it onto their four sons and three daughter-in-laws. Their family home is now a workshop, Alfarería Doña Rosa, where Doña Rosa’s grandchildren sell their pieces and stage demonstrations for tourists. Each member of the family exhibits their work in one section of the grandroom. Since the pieces are unlabeled, one may find it difficult to differentiate between each family member’s work. However, this is not obvious since the pieces are not identified as such. If one were to inquire about personal style, the differences become more noticeable. The passing down of knowledge not only creates a sense of belonging and fosters continuity, but shows how adaptation is integral to traditional craftsmanship. As each generation learns, they add their unique perspectives and experiences to the practice. By continuing their craft they shape their legacy and challenge the neoliberal hegemony which forces individualism and leaves little space for traditional practices and craft. Through these practices, they actively create a bridge between the past and the future.

Photographs of Doña Rosa and family sourced from Alfarería Doña Rosa website and from Mexican Folk Art From Oaxacan Artist Families by Arden Rothstein. Pottery images taken by Miren Neyra Alcántara.

Sources:

Rothstein, Arden, and Anya Rothstein. 2007. Mexican Folk Art. Schiffer Publishing.

Alfarería Doña Rosa