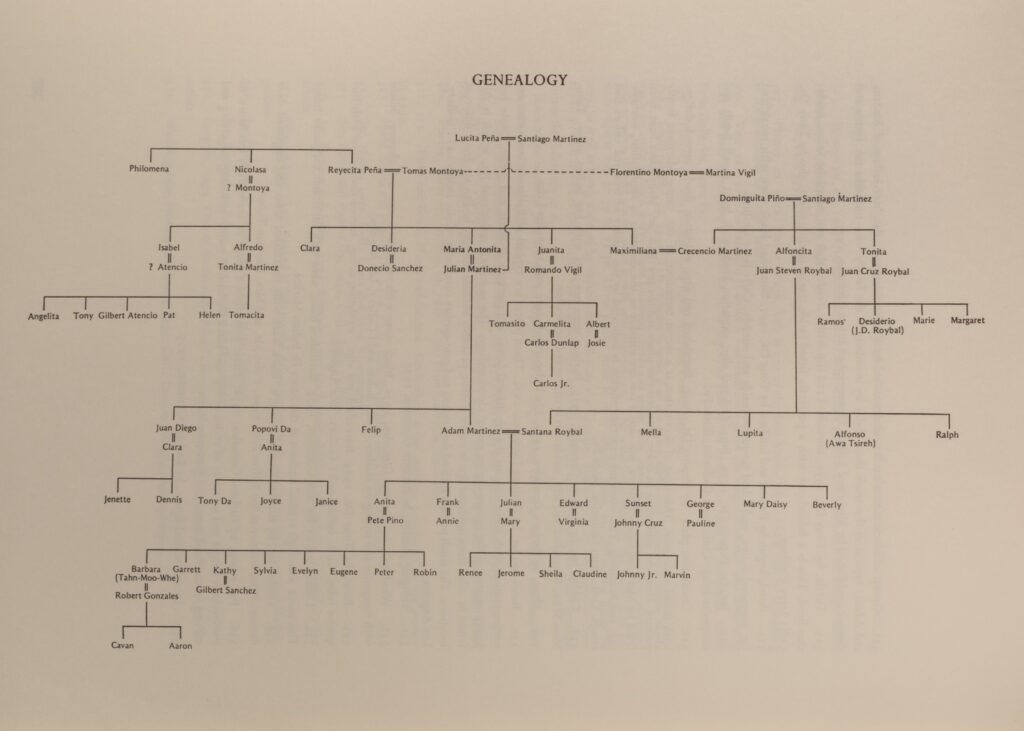

Maria Martinez (Tewa Pueblo) was born around 1886 in San Ildefonso, New Mexico. She is the matriarch of at least five generations of potters famous for making unique black ware. In Pueblo culture, pottery has always been a tradition. In 1908, Dr. Edgar Hewett, New Mexico archaeologist and director of the Laboratory of Anthropology in Santa Fe, had excavated some 17th century black pottery shards and, seeking to revive this type of pottery, Hewett was led to Maria. Through trial and error, Maria rediscovered the art of making black pottery. She found that smothering a cool fire with dried cow manure trapped the smoke, and that by using a special type of paint on top of a burnished surface, in combination with trapping the smoke and the low temperature of the fire resulted in turning a red-clay-pot black. Maria Martinez and her husband Julian revitalized Pueblo pottery and transformed typically utilitarian objects into works of art that gained international attention.

Maria and Julian always made their pots together. They experimented with firing, burnishing, and decoration together. Maria would build the pots and Julian would decorate. Through Julian, the avanyu, the horned water serpent, became a common motif in Southwest pottery. Maria and Julian didn’t only share their knowledge with their family, they also taught anyone at San Ildefonso who wished to know how to make the black ware. Their collaboration, inventiveness, and sharing is what kept these traditions alive. The practice of pottery has been and continues to be an inherently communal form of intangible cultural heritage. Maria, as well as other Pueblo potters, recognized it as such and thus kept creating, maintaining and transmitting it.

A common scene in the Martinez household, Maria teaching the younger generations the traditional practice of making pottery. Maria’s children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren have memories of learning pottery at her house. The passing down of knowledge is the lifeblood of these practices which passes down traditions and values. This exchange becomes more than learning skills, it also creates a sense of identity providing a link from our past, through the present, and into our future. When asked how she learned pottery, Martinez said she learned by watching her aunt Nicolasa during the times she spent at her house. There was no teaching involved. “Nobody teaches pottery,” Maria said. There is then, a kind of observation-instruction that is continuous in the structure of each day. It is a real direct learning– through imitation, from demonstrations, by watching. In this way, through subtle repetition yet organic process, Maria showed not only her family but also the pueblo community their method of making black pottery so they could make it too.

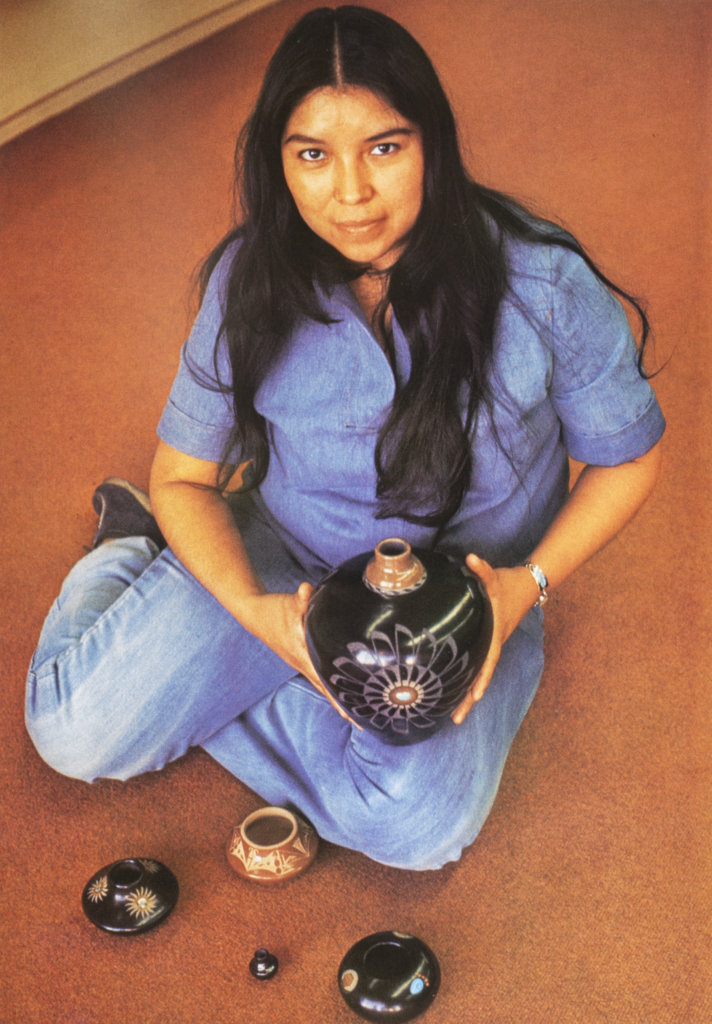

Barbara Gonzales, the great granddaughter of Maria Martinez, learned the basics of pottery when she lived with her from age five to ten. Barbara says pottery making was such an integral part of Maria’s family that she organically assimilated the skills simply from being in the presence.

Seed pots were a matter of survival for many Indigenous people. Seeds needed to be stored properly until the next planting season. The small, hollow pots were made to ensure that the seeds would be kept safe from moisture, light and rodents. Although seed pots are no longer necessary, they continue to be made as decorative works of art.

Learn your culture and nationality. Learn your land. Learn where to find your own clay source. Come up with your own design and revive your own traditional art. Learn your own traditions.

Barbara Gonzales for Hyperallergic Magazine.

The piece above is made by Marvin Martinez, Maria’s great grandson, and his wife Frances. Marvin and Frances learned through their family how to make pottery, being always surrounded by potters they still create their pieces in the traditional Pueblo way. Similar to Maria, Marvin and Frances make their pieces together. Maria and her husband Julian collaborated on most of their pieces with Maria building the piece and Julian decorating. Their exposure to multiple potters has given them a profound appreciation for the traditional designs started by his family. Both are now teaching their children the old-style pottery taught to them.

‘There is a beauty that our pottery brings to your eyes, wonders that it brings to your minds and the loving memories that it brings to your heart. Continue to love and enjoy the ‘gift of beauty’ the art of traditional matted ‘black on black’ pottery.”

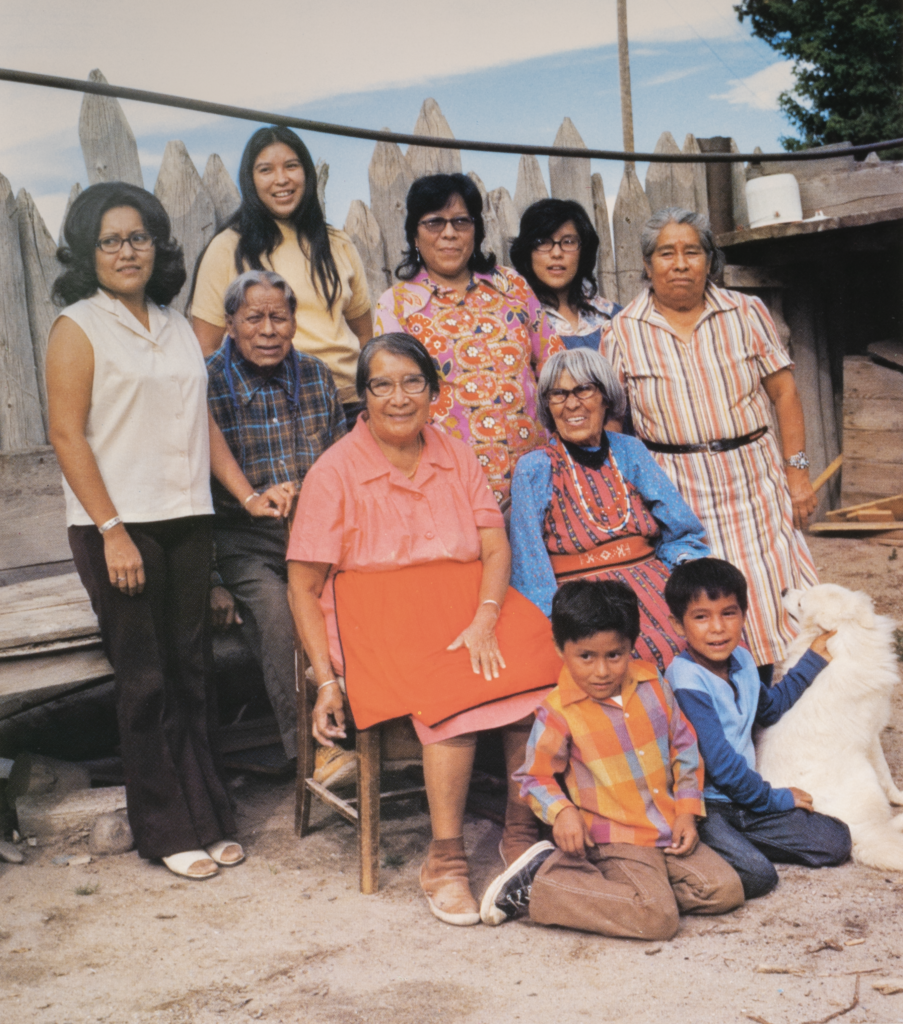

The Martinez couple

Five generations, and counting, of Martinez’s family make pottery. Everyone has their own style and design choice, but all have worked in the Maria-Julian polished black tradition at some point. Martinez, sitting at the bottom of the steps, made a unique contribution to the Pueblo community and left a living tradition that continues to this day.

The Sunbeam Gallery

The Sunbeam Gallery can trace its existence back to the early 1970’s starting life as a small, unused, traditional one-room house on the North Plaza of San Ildefonso. Belonging to Santana Martinez, wife of Adam Martinez; their eldest granddaughter, Barbara Gonzales (Tahn-Moo-Whé, Sunbeam), a potter in her twenties at the time, asked for permission to use the building as a simple candy & snack shop for the children of the pueblo. Occasionally a visiting tourist would walk in and inquire about the potters of the pueblo. Barbara, being a direct descendant of the famed pueblo potter Maria Martinez as well as a pupil to both her & Santana, began displaying a few pieces of her own work in the small shop.

As time would tell, it proved to be better than worthwhile, as it not only allowed Barbara (a young mother of, at that time, two boys) a means to extra income, it also allowed Adam & Santana a direct outlet to sell their pieces as well. It proved to be a solid decision and the property began to evolve into more of a gallery, while staying true to its roots as a candy & snack shop for the pueblo children. It remained functioning as such until the early 2000’s, at which time the business was moved to its current location off of the plaza & onto the Gonzales property. Affectionately the old building remains known as the Village Store by all those old enough to remember buying candy & snacks from it. (Excerpt from the Sunbeam Gallery website).

Photographs of Maria Martinez and family sourced from The Living Tradition of Maria Martinez by Susan Peterson. Pottery images taken by Miren Neyra Alcántara.

Sources:

Andrea Fisher Fine Pottery. 2024. “Marvin and Frances Martinez.” Andrea Fisher Fine Pottery. https://www.andreafisherpottery.com/.

“Marvin Martinez Archives • Native American Collections.” n.d. Native American Collections. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://nativepots.com/brand/marvin-martinez/.

Mendoza (JEM), Joelle E. 2023. “The Living Legacy of Pueblo Potter Maria Martinez.” Hyperallergic. September 3, 2023. https://hyperallergic.com/842172/the-living-legacy-of-pueblo-potter-maria-martinez/.

Peterson, Susan. 1989. The Living Tradition of Maria Martinez. Tokyo: Kodansha International.