One can appreciate the beauty of a piece whether or not we know who made it. Most craft practitioners never considered signing their art. Maria, Doña Rosa, and Juan did not sign their pots originally. However, it wasn’t until they all encountered some level of Western attention that required them to do so. “The concept of a signature occurs when a craft leaves the true communal formula and objects are given connoisseur value not related to their original utility.” 1

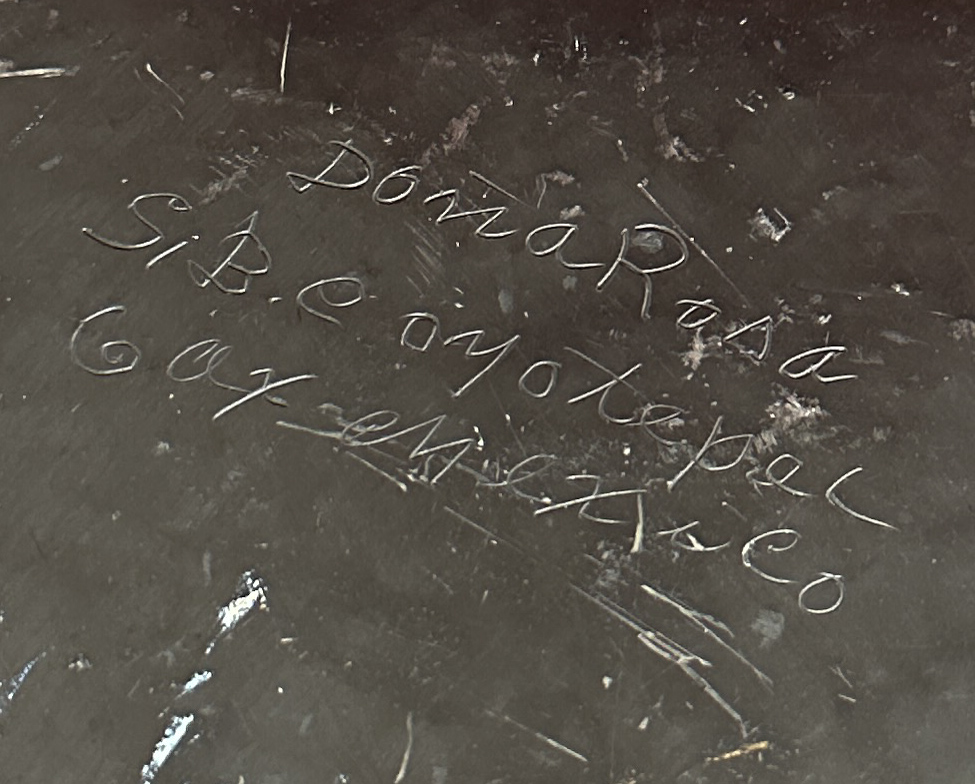

Pictured here is Doña Rosa. the photograph was taken by American photographer Robert Natkin. In 1948, Natkin was commissioned by the Mexican Tourism Bureau to capture images suitable for promoting tourism. One of the towns he visited was San Bartolo Coyotepec. He took several pictures of people making pottery, including Doña Rosa. However, she was never named or identified. Even unnamed, Doña Rosa received international attention thus showing how the Western gaze ignores and sidelines the artisan by means of exotification.

Doña Rosa’s innovation made the pieces more breakable, but it made the pottery far more popular with Mexican folk art collectors, which included Nelson Rockefeller and Jimmy Carter, who promoted it in the United States. Her name quickly became known and she started signing her pieces. Although the concept of signature hiked up prices for barro negro pieces, Alfarería Doña Rosa remains to this day the only place where barro negro is affordable to anyone who visits it, thus challenging the Western “fine art-ization” and “hierarchical-ization” of communal craft.

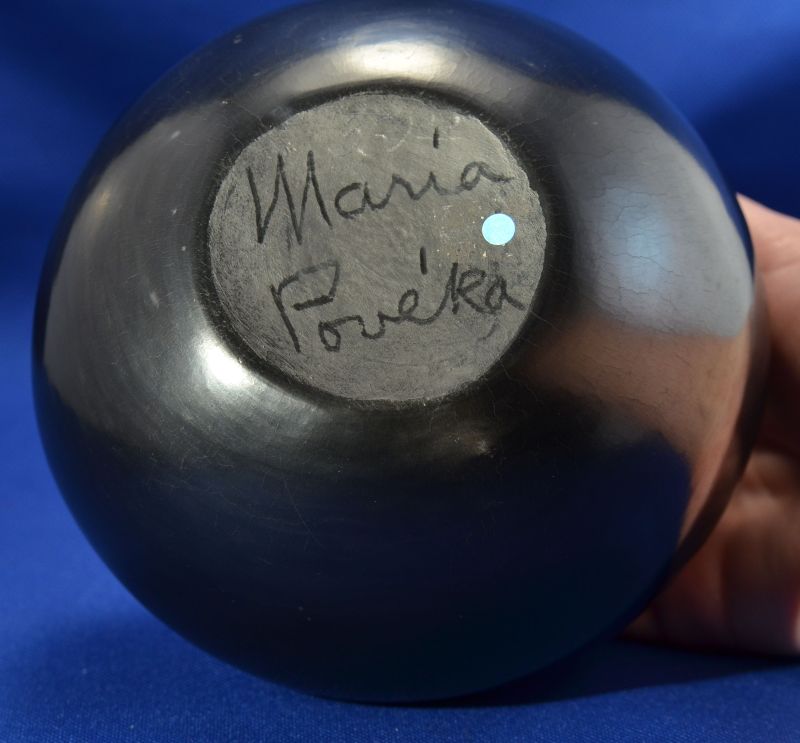

By the mid-1920s, a book was published by the director of the Museum of New Mexico which encouraged Maria to sign her pots, which were beginning to be regarded as works of art rather than household or ritual vessels. Throughout her career, Maria signed many pots with different signatures and often included many of her collaborator’s names. Maria attached no particular value to her signature. Sometimes, Maria, Santana, and Adam were taken to museum storage rooms to look at the many old unsigned pots in the collections. They could generally pick out the pottery of their own pueblo, although not always the name of the potter or decorator. No doubt there are “marias” that still go unidentified and other pots she did not make that are attributed to her. Maria delightfully and wisely mixes both the communal and the “name artist” attitudes.

Pictured here is a “certificate of authenticity.” It certifies a “completely handmade work of art by the Original Potter Juan Quezada.” As popularity rose for Quezada, the need for an “authenticity check” grew. For Juan Quezada it was anthropologist Spencer MacCallum who “discovered” him and his work. At the same time that Quezada gained recognition, everyone in Mata Ortiz most likely have pottery knowledge separate from Juan Quezada’s legacy, and at the same time they also benefit from the international recognition he gained over the years.

Sources:

“National Museum of Women in the Arts.” 2023. NMWA. April 27, 2023. https://nmwa.org/art/artists/maria-martinez/#:~:text=By%20the%20mid%2D1920s%2C%20Martinez%27s.

“Potter #1 – Robert Natkin Photography.” 2013. November 14, 2013. https://robertnatkin.net/mexico-1949/potter-1/.

“Signatures.” n.d. MariaMartinezPottery.com. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.mariamartinezpottery.com/signatures.html.

“Touched by Fire: Signing Her Art.” n.d. Miaclab.org. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://miaclab.org/exhibits/maria/ar_signing.html.

- Peterson, Susan. 1989. The Living Tradition of Maria Martinez. Tokyo: Kodansha International. ↩︎