“They tried to rig the game, but you can’t fake influence.” But what did Kendrick Lamar mean by that in his second halftime performance on February 9th, 2025, during Black History Month? The Super Bowl is the greatest stage possible for an artist in America and is one of the highest honors in one’s career. Millions of people from across the world chime in just to watch the halftime show, eager to see what songs the artist will stun the audience with. Because of the expensive tickets, most people who watch the Super Bowl watch it from their screens, something known very well by both the NFL and Apple Music, which is a perfect opportunity for the camera to also perform with the artist(s). The Compton, Los Angeles-raised Black rapper Kendrick Lamar made a splash in 2024 through his victory over Drake in a rap beef, and the scrutiny intensified when he was revealed to be headlining the Super Bowl Halftime Show. However, after his performance, thousands of opinions claimed that his was the “worst halftime performance they’d ever seen”. In his 1935 essay, “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, Walter Benjamin discusses the impacts of art of film on the artistic values of the public viewers, including their reactions to said art. The performance reveals a special part of the most recent Halftime Performance. Benjamin’s theory of manipulation of mass public reaction through film emphasizes Kendrick Lamar’s statement of subverting expectations of the “Super Bowl Halftime Performance”, promoting Black celebration and a critique of American division through the list of songs and his adlibs, the nature of the production, and the public reception to Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl Halftime Show.

Kendrick Lamar’s song choice and adlibs deepen the defiance against expectations of the “Super Bowl”, allowing for a loving message to Black audiences to celebrate while reminding the audience that America is deeply flawed. As written before, the Super Bowl is a massive form of entertainment, so many viewers don’t expect anything but that form of entertainment, which Benjamin also notes when he writes that today, when there’s such an absolute emphasis on the exhibition value of a work of art, it becomes a “creation with entirely new functions”, rather than being a simple concert, the actual “art” of it being almost an afterthought(Benjamin, 7). Every song choice and how they are listed one after another is up for careful scrutiny. What is being proposed in this essay is that Kendrick Lamar is aware of how art is consumed today and uses it to his advantage to make specific statements. What comes out of his mouth into the microphone matters as a performer on the Super Bowl stage. Starting with the ad-libs he says between each song, it’s incredibly important to note once again that he is performing in front of Donald Trump, the president of the United States, and says “the revolution ‘bout to be televised; you picked the right time but the wrong guy.”(NFL, 1:20). The first part of this quote is a direct reference to “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” by Gil Scott-Heron in 1971, a critique on the role of media and entertainment in Black liberation, something that reflects Lamar’s own critique on American division and what the media, and the Super Bowl, choose to focus on during a time of great strife. The second part of the quote is also suspected to be a jab directly at Donald Trump and his supporters, indicating that Americans have voted for the “wrong guy”. His set list is also a helpful clue into how Lamar is manipulating the idea of public reaction, because in any other Super Bowl, the idea would be to have people entertained by a performance of songs that are the typically most popular. That’s not what Lamar does. His setlist for the 2025 performance is diverse in age and in rhythm, performing songs from his newest album “GNX”, and songs that were released 10 years before, namely “HUMBLE”. Some of these songs were not the “most popular”, but it highlights Lamar’s ability to maintain a form of control over his Super Bowl performance despite being scrutinized so heavily to make his own form of celebration as a Black man during Black History Month. The commentary of a celebration of Black culture in America can also be seen just from the performance of “All the Stars” with SZA, a beloved song from the movie that also celebrated Black Diasporic culture, “Black Panther” in 2018. Furthermore, later in the show, right before he teases a performance of “Not Like Us”, the five Grammy-winning song that solidified Lamar’s decisive victory over Drake in their 2024 rap beef, he says that he wants to perform their “favorite song”, but “you know they like to sue”, referring to Drake suing the Universal Music Group for “Not Like Us”’s explosive success(NFL, 7:05). And because of that success and lawsuit, it was at the same time, the most anticipated song at the Super Bowl, but also the most controversial. It directly calls Drake a pedophile and implicates his entire label as a group of predators on a stage where millions of people are watching closely. The act of performing this song is a direct act of defiance, not only against Drake, but once again, against the very idea of the Super Bowl as a form of entertainment, because as Kendrick Lamar states soon after, “forty acres and a mule, this is bigger than the music. They tried to rig the game, but you can’t fake influence”(NFL, 10:07). Most people might not understand this reference either– it is a reference to a promised reparation given to freed enslaved people, giving them the right to land and the right to work on said land after the Civil War. However, this was a promise unfulfilled, as Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, rescinded the order and gave that promised land back to Confederates, rather than the people who actually worked on them. The reference is a direct critique of American culture and highlighting Black people’s complicated relationship with it– emphasizing Lamar’s consistent reference to racial politics in his music and his performances, imprinting the fact in the mind of every viewer who witnessed the Super Bowl the night of February 9th.

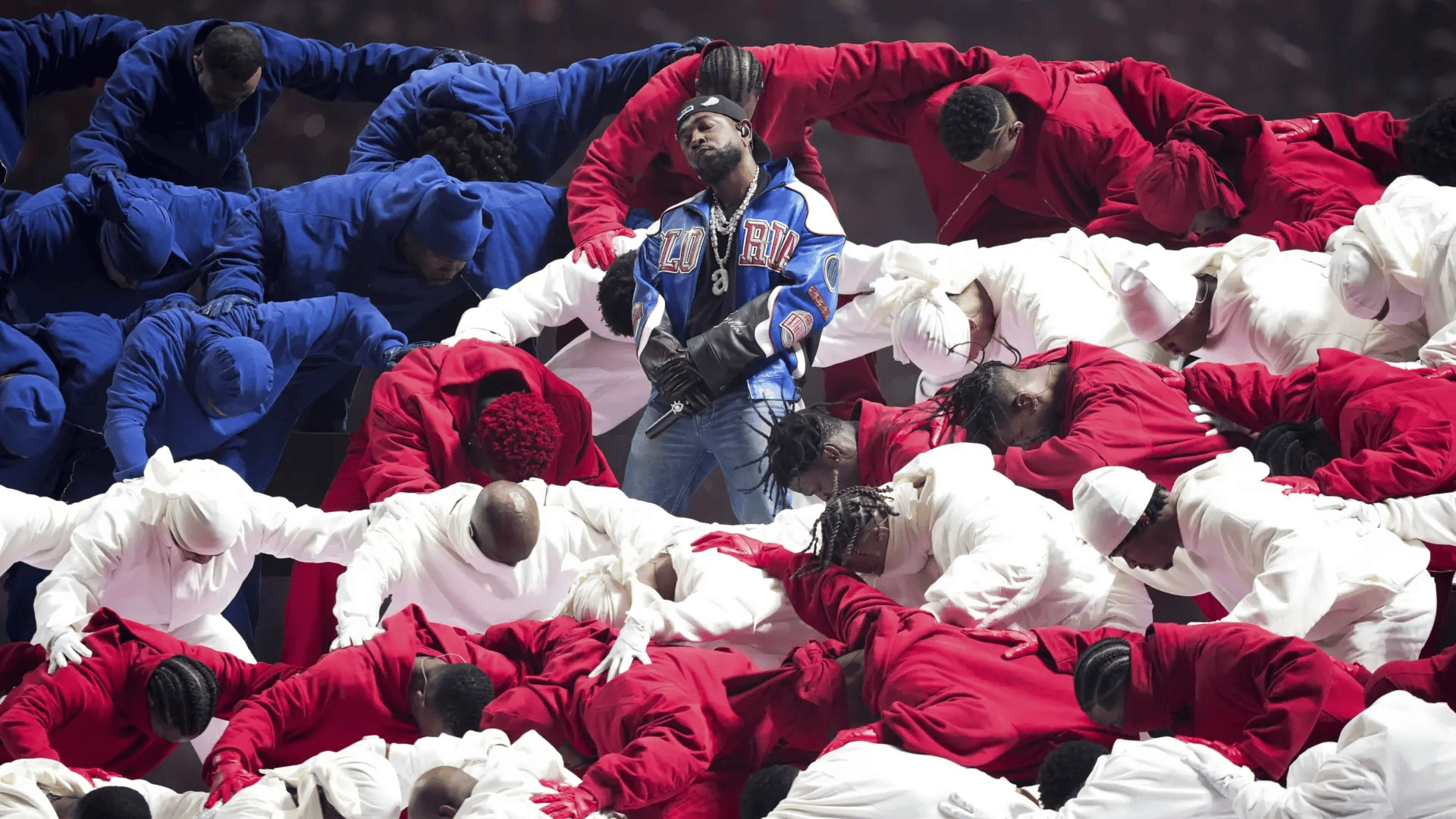

Of course, it was “bigger than the music”, because apart from the actual song listing itself, the entire production of Halftime Show performance also deepens the message of Black celebration and American division. First of all, as said previously, Lamar’s intentions within his music are always authentic, frequently finding a way to include racial politics within his performances, even on one as large and White as the Super Bowl Halftime. This is a point that also connects to Benjamin’s in a few ways. First of all, he asserts that when it comes to a filmed performance, it matters that the “actor” is representing himself, which Lamar does throughout the performance in many ways, deepening its impact(Benjamin, 10). Secondly, the stage is also extremely important, reflecting Lamar’s critique on the division and inhumanity seen in American culture, it derives from the “capitalistic exploitation” seen in Western Europe, where now, the “film industry is trying hard to spur the interest of the masses through illusion-promoting spectacles and dubious speculations”, which is at the heart of the Super Bowl performance with so many eyes watching. It is at this point that the viewer at home watching it on a screen comes into focus as well. The reason this point needs to be emphasized first is to allow the production of the Super Bowl to be seen in a different light, emphasizing both of Kendrick Lamar’s messages. Context matters greatly. First of all, all of the performers are dressed in red, white, or blue, or a combination of the two or three– in the style of the American flag. Secondly, there is the appearance of Samuel L. Jackson dressed as Uncle Sam, and Serena Williams dancing in blue and white. Thirdly, and the most relevant fact, is that all of the performers were Black. The movement of the camera allows for viewers to pay attention to this closely, allowing those three facts to become a highlight of the Super Bowl, and creates two statements: one, that Black people belong in America and belong in the colors of red white and blue, and two, that Black people deserve to be celebratory while wearing those colors and performing on that stage. Samuel L. Jackson’s lines are a huge clue of this, when after the performance of “Squabble Up”, while dressed as Uncle Sam, he chastises Lamar, saying “too loud, too reckless, too ghetto”, asking him if he really knows how to “play the game”(NFL, 2:50). This also relates to the game controller-like setup of the stage. The meaning of this relates to the idea of the American Dream of making one’s way to happiness from nothing, like a game that has always been at the disadvantage of Black Americans since Reconstruction. It relates to one of the tools related to Black survival in a country that doesn’t consider them human, doesn’t think they belong in America despite being the ones who built it, and part of those tools lies in Jackson’s declaration of Lamar being “loud” and “ghetto”, something Black people developed respectability politics to combat against in their attempted assimilation into American culture after being enslaved. Black culture and white culture have always been at the opposite ends of logic and presentation, yet they are inextricably linked, one not being able to exist without the other in America. Which is also why Jackson says that songs like Lamar’s “luther” and “All The Stars”, which were more uniform in their choreography like military marching bands, are “what America wants– nice and calm”, rather than upbeat trap songs like “euphoria” and “squabble up”(NFL, 9:51). This attention to the production in the Halftime Show demonstrates Lamar’s underlying desire amidst the illusory capitalistic entertainment of the Super Bowl to highlight the glory of Black culture, even in a country that does not want us to highlight the humanity and richness and loudness of it or understand it.

To continue with the idea of understanding, the reception towards the Super Bowl Halftime performance, particularly from White Americans, might be the biggest indication that Kendrick Lamar employed Benjamin’s theory of public manipulation through film and performance. It was written before, but the majority of the viewers both watching in-person or on the screens will not understand the many references and meanings within Lamar’s Super Bowl performance, because the Super Bowl has historically not been a performance where people have to necessarily think. Benjamin corroborates this statement through his assertion that mass is what truly matters in art today, saying that “quantity has transmuted into quality. The increased mass of participants has produced a change in the mode of participation”, yet an unspoken rule for this is that the art form now “must not confuse the spectator. Yet some people have launched spirited attacks against precisely this superficial aspect”(Benjamin, 17). The public is put into a position not unlike a “critic”, but “this position requires no attention. The public is an examiner, but an absent-minded one”(Benjamin, 19). This fits what has been repeatedly said about the state of media and entertainment today, as stages where the audience, especially the ones viewing from their screens, do not usually feel that they have to think while they view the performance, and the film industry, along with the NFL and Apple Music, in this case, play into this because it garners more attention, and thus, more money. While Benjamin’s assessment may seem harsh and appears to underestimate the viewer’s capabilities of understanding, social media has revealed that many members of the American public fit this “absent-minded” viewer’s position perfectly. On X and TikTok, many viewers complained about various aspects of the performance, one of them saying that they “thought the message was to ‘End Racism’”, yet “didn’t see a single white dancer on stage”(@realtalkstruth, 2025). Politicians and others complained that they “couldn’t understand what he was saying”, calling it a “Black Nationalist” show, “the worst halftime show they’ve ever seen”, including Matt Walsh and Matt Gaetz(@fearedbuck, 2025; @mattwalshblog, 2025). When reading these, it is incredibly important to note once again that on a large stage that is so wrapped in White supremacy and capitalism, a majority of the people with these grievances are Republican White men, the exact opposite of whom this performance was meant to celebrate during Black History Month. The idea of Lamar not being able to be understood is another racist reference to African-American Vernacular English and rap culture, which were long criticized for “not being proper English”, highlighting why Kendrick Lamar would critique White American culture so much, because their argument as to his lack of qualifications to perform provided him all the reason he needed despite him being rightfully chosen to be the person who headlined the 2025 Super Bowl. Furthermore, these reactions demonstrate Benjamin’s theory because once again, these viewers don’t want to think about what each element of the show means, why Lamar chose the songs that he did, how he framed the entire show and production of it, it is proof that these days, because of how art is made into an exhibition, it creates “absent-minded viewers” who are placed in the position of the critic because their viewership is what gives money to the people behind the production of the Halftime Show. Those who understand and appreciate Black culture and Black people were able to pick up pieces of Lamar’s meanings behind the clothing and the choreography and therefore appreciate the beauty of the performance, gaining the artistic appreciation that Benjamin describes society losing in the modern era of film and showcases such as the Super Bowl. Public reception to this Super Bowl shows just how much society has lost the ability to see quality in art for what it truly is.

Kendrick Lamar, in front of Donald Trump, the president of the United States, made a statement that threatened to shake the foundations of the American Dream, at a time when people began to wonder what that phrase truly means, on the biggest American stage there is. His performance was a celebration of Black culture, and a massive critique on the anti-Black, divisive, capitalist nature of American culture, including the culture of the Super Bowl, which demands nothing but entertainment from the performers. However, Kendrick Lamar is not like the other performers, as he intends to include politics into every performance he has, no matter how big or constricting the stage, which can be seen in the words he chose, the songs he performed, even down to the clothing and choreography. Kendrick Lamar’s Halftime Performance set a precedent for future artists, and for Black viewers across the country that Black influence and celebration is an indelible part of American culture, one that simply cannot be swept away, even in the storm of White supremacist culture.

Citations:

- Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Illuminations, 1935, pp. 1–26, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv47wfgm.7.

- “Kendrick Lamar’s Apple Music Super Bowl Halftime Show.” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KDorKy-13ak. Accessed 2025.

- @realtalkstruth, “I thought the message was to ‘End Racism’.,” 9 Feb 2025, 10:41PM, Twitter. American Citizen 🇺🇸 on X: “I thought the message was to “End Racism.” Yet, during Kendrick Lamar’s halftime show, I did not see a single white dancer on stage. I’m all for artistic expression, but shouldn’t inclusivity go both ways? What happened? #SuperBowl” / X

- Ocho, Alex. “‘Pokimane Says “Only White People Hated” Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl Halftime Show.’” MSN, 11 Feb. 2025, www.msn.com/en-us/entertainment/celebrities/pokimane-says-only-white-people-hated-kendrick-lamar-s-super-bowl-halftime-show/ar-AA1yNarx.