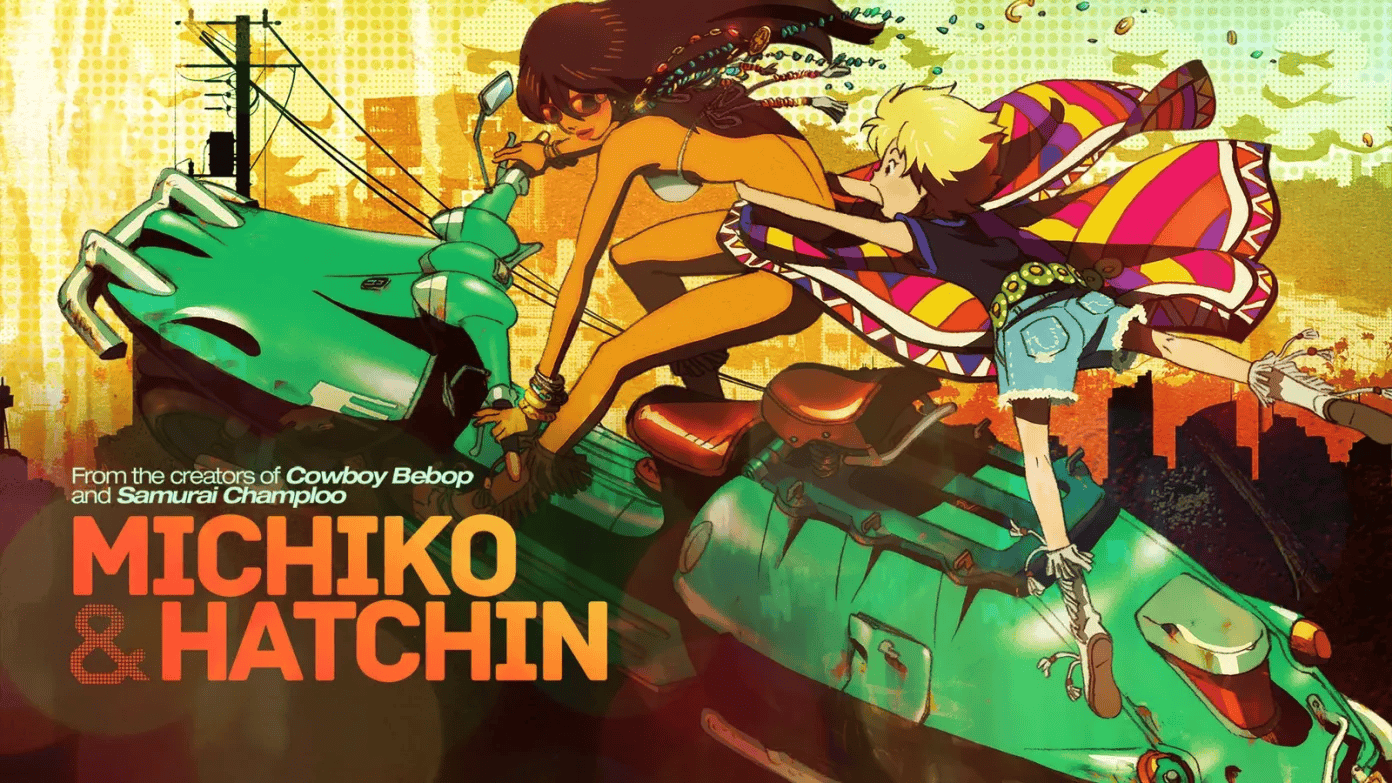

Black nerds, or Blerds, have long been missing representation in media, including video games, comics, and of course, anime. After the Meiji Restoration in 1868, when Western values and technology entered Japan, anti-Black rhetoric. When Japanese animation, specifically anime, came about in the ‘60s, the presence of Black characters was kept to a minimum, and if they were included, they were used as comic relief, or background characters at best. Japanese media had, since the 1920s, been adopting forms of anti-Black racism, such as the acceptance that Black people were the “incarnation of apes”, and the widespread publication of the Japanese edition of Lil’ Black Sambo as a children’s book(Reece, 31). However, in October 2008, an anime called Michiko & Hatchin aired, starring an Afro-Brazilian woman, Michiko Malandro, who escapes from prison to rescue 10-year-old Hana Morenos from her abusive foster family to take her on a journey across the country to find her father and Michiko’s former lover, Hiroshi Morenos. Michiko & Hatchin, being the first anime to have a Black female protagonist in the 2000s, quickly became deeply beloved by Blerds, though it had its own flaws and critiques present. Michiko & Hatchin’s characterization of its protagonist, Michiko Malandro, highlights the influence of Western misogynoir in Japanese anime through her racially ambiguous, sexualized appearance and the angry Black woman stereotype, despite how groundbreaking it is for both Western and Japanese anime.

The consistent hypersexuality of Black women is present in Western media, and it bleeds into Michiko & Hatchin, along with intentional racial ambiguity in Black characters. First of all, Black women have long been labeled “Jezebel”, sinful seductresses who have been oversexualized since antebellum periods, branding them as inherently sexual beings. This can be seen in how Black women are represented in television, cast as “more sexualized and less feminine than white women”(Jackson, 13). This, of course, is seen throughout Michiko & Hatchin, beginning with the very first scene of the show where Michiko’s cleavage is on display while she escapes from prison(“Farewell, Cruel Paradise!”, Michiko & Hatchin, 00:09). In every public space, she is sexualized by other characters, often staring at her breasts, her hips, and her full lips. While she is the protagonist of the show, and therefore viewers’ focus is from her perspective, she is the brunt of most of the sexualization in the show, presented as a “sexy diva”. It becomes problematic when thinking about how international viewers could view someone like Michiko, especially considering how fetishization towards Black women has also blended into Japan. Delving further into Michiko’s appearance, she is a brown-skinned woman with thick lips and silky-straight Black hair. The producers and character designers of the show confirmed that she was inspired by the singer, Aaliyah, who has the same appearance. However, in an anime art style, Michiko’s appearance is prone to becoming racially ambiguous, leading some to speculate whether she is Black or not, especially in the Japanese dubbing. Deborah Elizabeth Whaley, in her chapter describing the presence of Black women in anime, uses Nadia: Secret of Blue Water(1990), possibly the first anime to have a Black girl as a protagonist, to highlight some of the possible motives behind Michiko’s appearance, writing that

“Fans report that Anno and his collaborators wanted to illustrate Nadia with coarse, curly hair, but conceded that if she was too conspicuously Black, Japanese, and international audiences might not relate to the character. … In other words, visually marking Nadia in a more ambiguous fashion, that is, as African, Asian, and ambiguous Other, opened up the possibilities of spectators’ identification with Nadia.”(Whaley, 131)

There are a few points that are worthy of highlighting, and one of them is the fact that the motive behind Nadia’s change in appearance is not malicious, and was done to help the main character of a story feel more relatable to an audience with her racial ambiguity. Through this decision, it can be speculated that the design behind Michiko might have had similar motives, to make her more relatable to international audiences while keeping her Aaliyah-inspired design. It is also important to note that one of the villains in this story, Michiko’s rival, Atsuko Jackson, is a dark-skinned woman with a large Afro, which may lead one to wonder based off of the information above if viewers were supposed to relate to her as well as their protagonist. These decisions raise an issue present in all forms of media relating to Black people, especially anime: why wouldn’t viewers find Nadia relatable if she had coarse hair, and why might Michiko’s creators have felt the same? Black audiences have long had to contend with attempting to relate to characters that might not look anything like them for as long as television has been created, and this decision speaks to the anti-Black racism present throughout nearly every culture in the world, that creators of an anime must change a Black character to cater to audiences who might be used to having media center around characters that might appear to look like them. If this was the case in Michiko’s creation, it shows that she is also a victim of this as well and an unintentional perpetrator in these potentially harmful anti-Black continuations.

Even if Michiko’s appearance might be racially ambiguous, her personality can lead viewers to think that she is Black right away, which is another issue. Her personality maintains the harmful stereotype of the “angry Black woman”. In her article that dives into the representation of Black people in the media, Sandra Jackson describes the racist stereotypes that are perceived of them, even if their race is not “visually present”. Their personalities must be depicted as “unreasonable, possessed of exaggerated strength, dissonant, disorderly, and engaging in excessive sexuality”, as “typical of the race” as opposed to “traits associated with whiteness– discipline, quiet competence and industry”, which are perceived as “atypical of Blacks in general”(Jackson, 13). Unfortunately, Michiko embodies a few of these “typical” traits, which is a problematic way that some viewers would be able to think she is Black immediately upon meeting her. In her thesis on the representation of Blackness in anime, Ermelinda Nancy Reece echoes this in her own analysis on Michiko, saying that Michiko is portrayed as “crass, rude, short-tempered and at times selfish. Her introduction is outlandish; crashing through a window on her moped”, and “fits the stereotype of an angry, loud Afro-Latina as well as being seen as an unfit mother” to Hana(Reece, 51). Her full introduction, as Reece outlines, is indeed outlandish, and the disco-style music that plays right after her moped crashes through the window helps emphasize a stereotype present in Western media: the “badass” Black woman, often seen in ‘70s Blaxploitation movies that layer onto the stereotypes present in Michiko’s personality(“Farewell, Cruel Paradise!”, 19:14). Adding onto the “angry Black woman” stereotype, her violent behavior is also consistent throughout the show, often threatening people and using force rather than words at times. Unfortunately, there are several layers that add onto her stereotypical personality. Viewers who watch the English dubbed version of Michiko & Hatchin will hear that Monica Rial, the White voice actor who voices Michiko, was directed to put on a sassier, almost “blaccent”, having Michiko curse and use AAVE to deepen her “Blackness” and her crass personality. This is something brought up in the anime as well by Hana, the child who Michiko is meant to act as a mother to, who tells Michiko that she has “seen [her] make too many people cry with the way [she acts]”(“Black Noise and a Dope Game”, 03:52). It shows the consistency and depth of Michiko’s bad personality, which viewers can attribute to Black women through this stereotype, and is harmful because Michiko is the first Black woman protagonist in anime since Nadia: Secret of Blue Water, and the first Afro-Latina. How she presents herself might set a precedent for future representations of Black women in anime, and having her perpetuate the stereotype of the angry, badass Black woman is a bit disparaging, especially for Black viewers who might relate to her the most.

Despite the flaws present in her portrayal, Michiko’s character is still groundbreaking for both Japanese and Western audiences, and that makes these flaws all the more subject to scrutiny. Returning to the topic of hypersexuality in Black women, Reece has an important detail mentioned in her thesis, writing that due to slavery, Black women were forced to be mothers, not only by nursing their enslavers’ children, but also due to being sexually assaulted by White men, and them being “pregnant on a constant basis was seen as a sign of hypersexuality, not taking into consideration the circumstances that caused it”, and with “hypersexuality and maternity being interlinked to one degree or another, Michiko Malandro might be considered an antithesis and that is a good thing”, as she is not Hana’s biological mother(Reece, 52). Her being Hana’s biological mother would deepen the idea that she is an unfit mother, since Michiko had been incarcerated since Hana’s birth, and would present a mother-daughter disconnection. While Reece’s argument does hold up in regard to maternity, unfortunately, it doesn’t take away from the fact that Michiko’s oversexualization does not come from it and does not end with it. Being hypersexualized by both men and women throughout the show, despite her clear refusal nearly every time she is seduced, which might not be the best example of how Black women might want to be portrayed in anime, adds onto the idea that they are hypervisible in any setting. Reece also discusses her personality, and how she is humanized by it, writing that by showing her “vulnerability around Hatchin”, it “contrasts the stereotype of African-American women being ‘bitter’ or ‘angry, just for the sake of simply being angry’.”(Reece, 52). This is an important thing to consider as well, because it shows that in several ways, Michiko does offset the Black woman stereotype in anime, and it shows that her creators might have taken the present stereotypes into account and worked to change how Black people are viewed to international audiences. However, what Reece does not touch upon is how her anger can be seen as exaggerated through her acts of violence toward others. As stated before, Michiko’s temper can turn violent, and can be seen through threats, slamming furniture, and moving to hit others, sometimes without using words to solve a conflict, which could deviate from showing that important contrast that the directors of Michiko & Hatchin might be trying to convey. Michiko is a very human character, and these flaws, including how she is seen in her own sexuality and how imperfect her life and personality is, make her much more relatable and engaging, but there are still stereotypes in that character that viewers, particularly Black viewers, might find off-putting, especially when she was created by Japanese people, those who don’t know what it is to be an Afro-Latina or an African-American. As Blerds who love anime, it is important to take note of this.

Ultimately, it would be remiss to say that Michiko & Hatchin is not groundbreaking for anime. It eliminates the idea that Black people, especially Black women, do not have a place in anime as protagonists. Michiko and Atsuko’s presence paved the way for other Japanese anime that have Black female protagonists, including Clock Striker and Carole & Tuesday, giving Black women a chance to shine in media that has exploited and excluded them for decades. Black feminine presence also helps tackle racism in the anime community, where anti-Black viewers will maintain that “there is no place for them in anime” because anime does not have or care about Black or Latine people, even if the shows are set in places other than Japan. However, Michiko & Hatchin is not without its flaws and its own stereotypes, and the next step in anime that stars Black women is to deconstruct the harmful stereotypes that surround them, including hypersexualization, the “angry Black woman”, and the “sexy diva”. Opening the doors for more Black manga artists, and Black voice actors, is one of the greatest steps anime can take to creating a space for Black enjoyers. Michiko is an incredibly positive character to Japanese and international audiences, and she is one of the pioneers of Afro-Latine presence in the media. It is her and Hana’s story that gives viewers hope that there is a next step after her, and that maybe there is a chance that anime does care Black people as much as they care about it.

Annotated Bibliography

- Reece, Ermelinda Nancy. “Exploring African American Representation within Japanese Manga and Animation from 1980 to 2019.” Order No. 27959314 Texas Southern University, 2020. United States — Texas: ProQuest. Web. 24 Mar. 2025.

This text is an in-depth student thesis for Texas Southern University written by Ermelinda Nancy Reece detailing African-American representation in Japanese media, detailing the spread of literature in Japan and how Japanese people came into contact with Black people, culture and stereotypes surrounding Black people, letting it bleed into anime and manga. Reece analyzes how Japanese people have engaged with Black culture, including rap, disco, and R&B, as well as engage with their Black citizens, highlighting tennis star Naomi Osaka(half-Haitian, half-Japanese).

Reece mentions Michiko as a Black female character in anime, and so I will use her analysis on Michiko, largely for my counterargument, but also to demonstrate how Jackson’s discussion of how Black personality is portrayed in general media onto Michiko Malandro, showing again how Western media and stereotypes have blended into anime, particularly Michiko & Hatchin.

- Whaley, Deborah Elizabeth. Black Women in Sequence : Re-Inking Comics, Graphic Novels, and Anime, University of Washington Press, 2015. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/smith/detail.action?docID=4305962.

This source helps explore the effects and depths of African-American representation within several forms of fantastical media, including comic books, superhero movies and anime(through an analysis of Nadia: Secret of Blue Water). Whaley discusses the impact of Black stereotypes on these specific forms of media, demonstrating the nuances of Black culture within both Western and Japanese media. Whaley uses Nadia: Secret of Blue Water to discuss how the protagonist, Nadia, set the standard for Black female portrayal in anime through her racially ambiguous appearance to increase, which is seen in popular anime like Bleach, Pokemon and of course, in Michiko & Hatchin.

For Michiko Malandro, although Michiko & Hatchin doesn’t contain superpowers the way Whaley focuses on in Chapter 4 of the book, Michiko’s racially ambiguous appearance corroborates Whaley’s argument of increasing a Black female protagonists’ relatability to international audiences. It also speaks to explain why her rival, Atsuko Jackson might have been designed to be dark-skinned, wearing a large Afro, showing that because she is the “villain”, she is meant to be less relatable to the audience, so she has “Blacker” features.

- Jackson, Sandra. “Encounters with Simulacra: The Media, Representations of Blackness, and Me.” Counterpoints, vol. 169, 2002, pp. 11–31. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42977469. Accessed 2 Apr. 2025.

Sandra Jackson is an Associate Professor of Education at DePaul University in Chicago, and a writer for the feminist journal Counterpoints, and this article talks generally about Black representation in American media, from literature to magazines to television, focusing on different parts of the representation, including the setting, the story, characters’ motivations and whether they live until the end of the program, whether the Black people are performing or not, and how she engages with them as a Black woman in 2002 who has grown up seeing shows like The Jeffersons(1975-1985), and Good Times(1974-1979).

For this article, because it talks about African-Americans and Black portrayal in Western media, which heavily inspired Japanese media, I will be using Jackson’s analysis of Black personalities on television, and specifically how Black women are seen and portrayed throughout history in American media, and to show how these harmful notions surrounding Black women might also reflect Michiko’s portrayal.