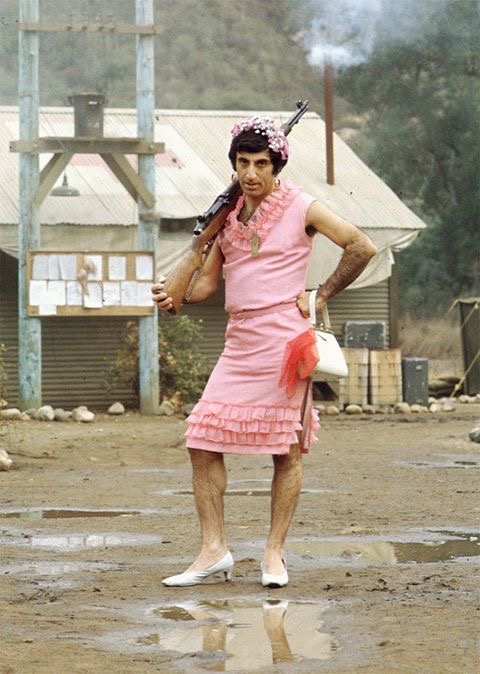

Jamie Farr as Corporal Klinger

An earnest and clever man, the cross-dressing Corporal Maxwell Q. Klinger of the television show M*A*S*H (1972) has long been a fan favorite of queer viewers. The show ran from 1972 to 1983, spanning 11 seasons. Set during the Korean war, M*A*S*H (1972) tackled the futility of war while following the antics of the 4077th mobile army surgical hospital in typical sitcom structure. Among the cast of surgeons, nurses, officers, and corpsmen is Klinger, played by Jamie Farr. A draftee, willing to do anything to get out of the army, Klinger is aiming for a “Section VIII,” upon which he would be discharged. Titled “Inaptness or Undesirable Habits or Traits of Character,” Section VIII of Army Regulation 615-360 aligned homosexual tendencies (such as cross-dressing) with mental conditions that warranted a discharge, honorable or dishonorable depending on the circumstances (Whitt 176). In his plot to evade service, Klinger seems to have woefully misunderstood the implications of a Section VIII, assuming the army would see cross-dressing as a sign of mental illness. On the contrary, the army saw it as a sign of homosexuality, an “undesirable habit or trait of character” which would attract a dishonorable discharge and greater social repercussions. Klinger’s friends are supportive of his protest against the war, and they humor his genuine interest in women’s clothing. Although progressive for the time, the show mainly uses Klinger’s appearance for comedic purposes. This portrayal of cross-dressing makes queerness into a spectacle and relies on jokes which reinforce harmful views of queer and trans people off-screen.

Klinger plays into the army’s pathologization of homosexuality, affirming the association between queerness and mental illness for the audience. Homosexuality was still considered a sexual perversion and mental illness in the early 1950s, and thus a reason for discharge under Section VIII. In her book “Managing Sex in the U.S. Military,” Jacqueline Whitt explains that army regulations were meant to discourage “disruptive” behavior in the U.S. military. As homosexuality became viewed as an identity rather than a behavior, these regulations were used to weed out queer people entirely. This view of queer and trans people (as the two were often conflated) permitted their dismissal because the military could claim they were unfit for service and disruptive to good order (Whitt 176). Klinger takes advantage of this army policy and creates this caricature of an insane man wearing dresses. Throughout the show he refers to himself as “crazy,” “nuts,” and once in a letter to a general says “here’s one more picture of myself to prove I’m mentally unbalanced and deservant of a psychological discharge.” Albeit in jest, the show draws a clear line between “crazy” and queer.

Unfortunately, when the audience sees what a Section VIII would mean for Klinger, the show fails to address the devastating weight of a dishonorable discharge. In season 2 episode 3, Dr. Sydney Freedman is called to the camp to evaluate Klinger upon the request of Majors Margaret Houlihan and Frank Burns. The psychiatrist is appalled at the obvious ploy to evade service but goes through the process anyways to satisfy Houlihan and Burns. Freedman gives Klinger papers to sign that would get him sent home under Section VIII, but he would be declaring himself a “transvestite and a homosexual.” Klinger is appalled at the assumption and retorts, “where do you come off calling me that?…I’m just crazy. All I want is a section eight.” By admitting he’s “one of those” as the show often puts it, he would be jeopardizing his future back home. Freedman even warns, “this will be on your record permanently. From here on, you go through life on high heels.” When a serviceman was dishonorably discharged under a Section VIII, their family was often informed so they would have nowhere to go once they returned home. In Klinger’s case, his family knows he’s bucking for a Section VIII, “My uncle got out of WWII this way, keeps sending me pieces of his wardrobe.” Although they briefly acknowledge the staying power of a Section VIII, neither acknowledge how a dishonorable discharge would ruin his life. If anything, Klinger is more offended at being called queer than he is threatened or frightened by Freedman’s bluff.

Besides presenting Klinger’s cross-dressing as absurd and inherently comedic, the sitcom also relies on gay jokes. When his friends and other personnel complement his outfits, even sincerely, the laugh track plays. Occasionally, these friendly remarks are played as flirtation, which gets an even bigger laugh. Cross-dressing jokes are the basis of his character’s comedic value, but they also open the door to gay jokes that involve the rest of the cast. In season 3 episode 11, Klinger remarks that he gets his lingerie from Chicago, to which Major John McIntyre says, “and it’s beautiful,” quick to defend himself with, “I hear!” In season 4 episode 3, Burns grabs Klinger’s arm and remarks, “another week in command and I’d have had you out of that dress” to which he responds, “I’m not that easy.” These jokes also offer Klinger a way of defending himself by shifting the accusations onto others, whether purposeful or not. Still, the joke that a straight man could be interested in Klinger only works under the assumption that his cross dressing is deceiving others.

This feeds into transphobic rhetoric and relies on the visual contrast of femininity and masculinity, and that of presentation and “reality.” He presents himself very feminine through clothing and accessories, but does nothing to feminize his features such as shaving or growing his hair long. This further emphasizes the contrast, adding to the comedic effect when he enters the frame. Klinger uses his ambiguous gender presentation to purposefully crosses boundaries and create conflict in hopes of being reported. In season 2 episode 3, the inciting incident for Burns and Houlihan’s report is when Burns mistakes Klinger for Houlihan. He walks into her tent, sees Klinger from behind dressed in a robe with his hair up in a bonnet, and bites his neck playfully. When Klinger turns around, upset, Burns jumps and accuses him of being a pervert. The writers use what scholar Tallia Mae Bettcher calls the “appearance-reality contrast” where “gender presentation (attire, in particular) constitutes a gendered appearance, whereas the sexed body constitutes the hidden, sexual reality” (Bettcher 48). Frank responds to his mistake with panic and anger, a response often used as a justification for violence against trans women when this “sexual reality” is found out. Burns calls Klinger a “pervert” and a “freak.” Houlihan goes to the commanding officer and demands that he is discharged, “Corporal Klinger has got to go. He’s a menace to the discipline and morale of this military establishment.” Yet in spite of Frank’s assertion that Klinger is a sexual deviant, the corporal is straight and cisgender which provides him with a certain deniability. Furthermore, he exhibits the very deception transphobes are afraid of, that a man could invade women’s spaces and seduce men under the guise of femininity.

The way the show handles Klinger’s sexuality furthers this rhetoric that anyone outside their gendered norm must be doing it to deceive others. Throughout the series, he uses his gender presentation to find ways into private women’s spaces, claiming innocence when he’s accused of invading their privacy. In this episode, he goes into Margaret’s tent without asking. When she yells at him and asks what he’s doing there he says, “Just borrowing a little of your shampoo, Major. It’s wartime. We all gotta help each other.” This reinforced the idea that trans women are really men “pretending” in order to prey on women. Klinger crosses boundaries like this because he wants to offend the army, and in doing so he encourages the Majors’ transphobia. Once again, he does this for his own gain, without regard for who else it might impact.

While imperfect, the show does address the absurdity of the army’s regulations through Klinger’s equally absurd response. The character is also using cross-dressing as a conscious protest against the war, and perhaps even military regulations. When Burns has everyone line up for morning muster in season 4 episode 1, he yells at Klinger, “how dare you wear that hat while in uniform.” The latter stands saluting and yells back, “it’s spring, sir!” Even though he’s protesting the U.S. military engagement in Korea, he’s doing it for selfish reasons. Klinger never sees the reality of the queer people who got a Section VIII discharge. He can’t empathize with them, as seen when Dr. Freedman calls him a “transvestite and a homosexual.” The doctor explains how the Section VIII would stay with him, but even then he’s only using it to call Klinger’s bluff, and neither are expected to reflect much on the issue. Lastly, Klinger’s reaction in that scene reveals a prejudice similar to that which he hopes to take advantage of.

The way Klinger plays with gender is reflective of various historical examples of military men cross-dressing for entertainment. Author Jay Mechling writes about the phenomenon in his book Soldier Snapshots, where he presents photos of various soldiers dressed as women. However, even though cross-dressing is an established and persisting form of amusement, many straight and cis men use it to further objectify women and to laugh at femininity. In many of the photos, Mechling points out how the service men grope and leer at their cross-dressing friends. Like the suggestive nature of these photos, many of the jokes about Klinger involve the men of the camp flirting with him and complimenting his body. Though it may have reflected past attitudes, the show’s portrayal of cross-dressing still invites misogynistic and homophobic jokes.

This is all put to rest at the beginning of season 8 when the gag suddenly ends. After bouncing between duties for seven seasons, Klinger takes on the job of company clerk and stops wearing women’s clothing. The show doesn’t address this change directly, but it’s presented as an evolution of character. He’s finally taking his responsibilities seriously now that his outfit depends more heavily on him. This maturation–and his heterosexuality–is solidified in the finale of the show when Klinger marries a local woman and gives her one of his old dresses to wear for the wedding. This scene contrasts an earlier episode where he had married his first wife over the phone, wearing the wedding dress himself. In the finale he also puts one of his finer dresses into the camp’s time capsule. These gestures represent the end of his cross-dressing for good since the war has ended, accompanied by another final declaration of heterosexuality as he marries the woman he loves. The representation of queerness on television is incredibly influential, and laughing at queer and trans people on-screen trivializes the issues they face off screen. The idea that transness is deceptive fuels anti-trans violence, especially against trans femmes. By having a character like Klinger, who cross-dresses while still appearing very masculine, the show reinforces the transphobic view that trans women are “really” men, and that their “sexual reality” must be revealed. Though there may not be a remix of M*A*S*H (1972) given its standing as a classic sitcom, the way queerness is represented on television, especially in comedies, can vastly improve. Some queer viewers take Klinger to be the most staunch ally, others decide he was in fact queer after all, so it’s not to say his character didn’t do any good. But harmful representation on screen can contribute to anti-trans rhetoric and violence off-screen. By examining where Klinger’s character could have been improved, we can take those critiques into account when writing new characters.