When we try to imagine what a super lady looks like, almost all of us can’t help but picture a skinny woman with big breasts, a lifted butt, wearing a tight, dark-colored suit, and that suit inevitably tears at the thigh after she fights a group of muscular men. Is there any image we could even imagine? It takes me quite a long time to recall a single female superhero who doesn’t look like that. Why can male superheroes wear loose outfits, heavy armor, or practical combat suits, while super ladies are always confined in skin-tight costumes that expose their chests, waists, hips, or thighs? This makes me sadly realize that we already live in a cinematic era saturated with the male gaze–an age where female heroes are expected to win not through strength or skill, but through beauty and allure; an age where women on screen are filmed through manipulative angles and displayed as visual commodities rather than complex human beings.

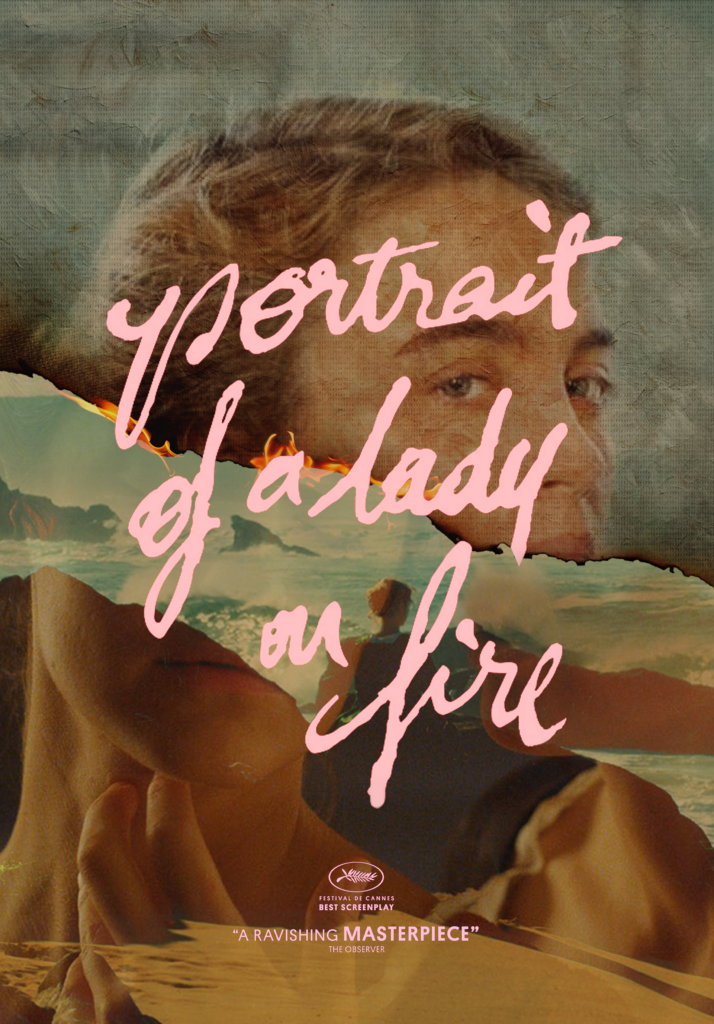

However, some directors have begun to resist this dominant structure by constructing new ways of seeing–ones that are rooted in empathy, equality, and female subjectivity. One of the most powerful examples of such resistance is Portrait of a Lady on Fire, a French historical drama film written and directed by Céline Sciamma. Set in late eighteenth-century Brittany, the film tells the story of Marianne, a painter commissioned to create a wedding portrait of Héloïse, so Héloïse’s mother could send this portrait to Héloïse’s fiancé–who has the right to decide whether he agrees to the marriage. This isn’t easy to achieve, because Héloïse refuses to marry as well as refused every previous painter who had come to draw her portrait. As Marianne secretly observes Héloïse in order to complete the portrait, the two women develop an intense emotional and romantic relationship. Through its deliberate absence of men, mutual recognition between two young ladies, and rewriting of myth, Sciamma’s film redefines the act of looking itself–transforming the male gaze from a tool of possession into a shared act of recognition and love.

Firstly, Sciamma replaces voyeurism in typical male-gazed movies by removing male characters. In traditional movies, women’s primary role in film is to be the object of the active male gaze–which is also the projection of viewers. According to Lacan’s mirror theory, “mirror stage” is the moment when a subject first recognizes its own image and forms a sense of self. Laura Mulvey applies this theory to film spectatorship– As the camera functions like a mirror, allowing viewers to project themselves into the position of the male protagonist, who controls the gaze within the narrative, as Mulvey said:

“As the spectator identifies with the main male protagonist, he projects his look on to that of his like, his screen surrogate, so that the power of the male protagonist as he controls events coincides with the active power of the erotic look, both giving a satisfying sense of omnipotence.” (Mulvey 12)

In this process, the spectator’s pleasure in looking is constructed through voyeurism–seeing without being seen–while women are positioned as passive objects of display. Hence, all viewers are effectively turned into male spectators, invited to peer into women’s lives as if observing a pet: a being stripped of privacy, autonomy, and the right to self-definition. Through this act of visual domination, women are reduced from independent subjects to accessories of male desire, thereby reinforcing patriarchal power not only on screen but in the viewer’s imagination. However, In Portrait of a Lady on Fire, this voyeurism rose from cinematic structure is destroyed by all female character structure. Except for a few male characters in the beginning and end of the film, the entire film is about women–the story between Marianne(the painter), Héloïse(female being painted), and Sophia(the maid). There is no male character present in the frame to dominate the narrative or dictate the direction of the story. Under Sciamma’s lens, three women are often framed within the same plane and illuminated by the same light. The camera neither looks down from above (signifying domination) nor looks up from below (suggesting reverence), and it never adopts a voyeuristic perspective. It avoids the voyeuristic angles commonly found in male-female narratives, where women are often filmed from first-person high-angle shots to visually reinforce a hierarchy with men positioned as superior and women as subordinate, or women occupy the visible space, while men remain in the shadows, unseen and unobserved. Instead, it observes them at eye level, creating a sense of equal presence between the viewer and the characters. This cinematographic choice places the audience in the same visual position as the women in the film–watching alongside them rather than watching them. The absence of men removes the camera’s need to “perform” for a male spectator, liberating both characters and audiences. Thus, there is neither a male spectator within the narrative nor a female character being subjected to the male gaze. As Sciamma herself notes in an interview, “This film is really about sharing the gaze, not taking it.” (Sciamma Little White Lies)

Secondly, this voyeurism is replaced by mutual recognition between Marianne and Héloïse. In the context of painting, there is always a hierarchical relationship between the artist and the subject being depicted: the artist, as the “gazer,” holds the power of observation and definition; the subject, on the other hand, assumes the role of being observed, becoming de-subjectified and reduced to an object of depiction and representation. As feminist art historian Griselda Pollock argues,

“High Culture plays a specifiable part in the reproduction of women’s oppression, in the circulation of relative values and meanings for the ideological constructs of masculinity and femininity. Representing creativity as masculine and Woman as the beautiful image for the desiring masculine gaze, High Culture systematically denies knowledge of women as producers of culture and meanings.”

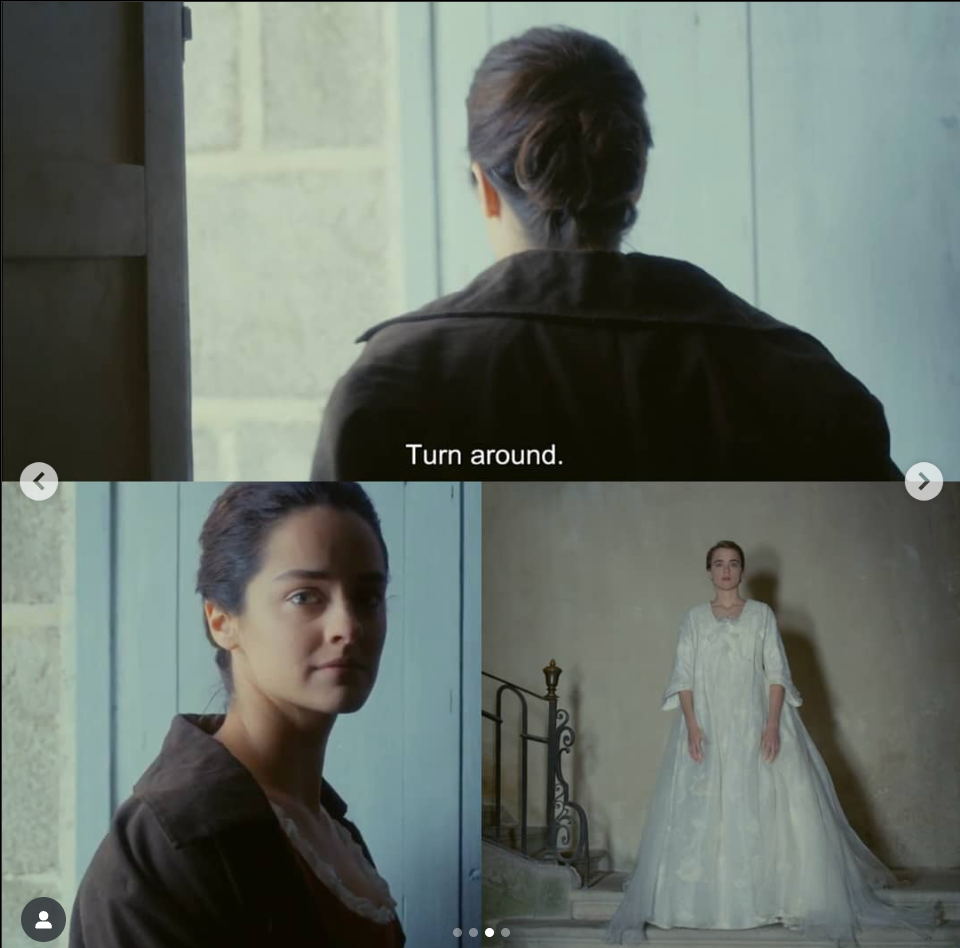

The structures of looking in art are always gendered; the painter’s gaze establishes the hierarchy of subject and object. When someone “looks,” they are not just an observer; they are also establishing control and definition over the other person. By gazing at the model, the artist is not only observing her; they are also determining who she is. However, in the film, Sciamma subverts this visual power structure. When Marianne is painting Héloïse, the dialogue between the two-

“I’ve been watching you.”

“You’re watching me, but I’m also watching you.”

-reveals a mutual and equal gaze. They communicate their feelings and admiration through mutually gazing at one another. At this moment, Héloïse is no longer just a passive model; she is an active participant as the subject of the gaze. Marianne’s gaze is no longer an extension of power but rather a medium for the exchange of emotions and understanding. As Sciamma puts it, “The narrative of the film is based on equality. I wanted to give both characters the same journey, the same screen time, the same intensity. The film is about that mutual gazing.” (Sciamma Vox) This “mutual subject-centered” visual structure transforms “creation” from a process of dominance and reproduction into a collaborative act of mutual understanding and appreciation. In this relationship, the power dynamics of “watching-being watched”are completely dissolved, replaced by a female visual ethics based on equality, empathy, and mutual recognition.

What’s more, through the strategy of myth rewriting, the film achieves a subversive reconstruction of gender codes. In the film, Héloïse reads the story of “Orpheus and Eurydice” after dinner. In the original myth, Orpheus was determined to bring back his beloved wife Eurydice from the underworld, but on the condition that he must not look back at her before leaving the underworld. When the two were about to reach the exit and see the sunlight again, Orpheus still couldn’t suppress the urge in his heart to confirm if she was still behind him, so he turned to look at her. At that very moment, Eurydice was pulled back to the Underworld forever, and Orpheus could never see her again. This myth is usually regarded as a symbol of “the desire to gaze and the inevitability loss of indiscipline”. As the subject of “gaze”, even though Orpheus knew that the price of looking back was an eternal loss, he still couldn’t suppress the impulse to “watch”. Eurydice, as the object being “gazed”, has no agency; she exists only within the structure of his desire and cannot direct it. However, in the film, Sciamma reverses this dominant relationship dominated by the male gaze. After reading the story, Héloïse said to Marianne, “Perhaps he turned back because she called him.” Which means, Orpheus turned to look not because he could not resist Eurydice as a tempting “object,” but because he wanted to respond to the call of an individual who stands equal to him. This sentence completely subverts the logic of the myth : Eurydice is no longer the object of gaze, but has become a subject with action and will–the one who chooses to be seen. She took the initiative to “ask to be seen” in order to achieve her last connection with her lover. Thus, the tragedy of “the male gaze leading to loss” in the original myth was transformed into “mutual recognition between women” — a gentle and equal viewing relationship. This rewriting also endows the separation of Orpheus and Eurydice with a unique female emotional dimension: Choosing to be seen becomes an act of love, and looking back becomes a way of preserving the other in memory forever. Unfortunately, this narrative perspective is often hidden in the grand narratives of male gaze films.

(source:https://www.instagram.com/p/CIgGvTTj8Z1/?img_index=3)

With the rise of feminism, audiences have begun to question the prevalence of male gaze in the visual culture. More and more directors have also sought to tell stories about female independence, attempting to transform the male-gaze dominated structure. Portrait of a Lady on Fire is one of the representative works within this feminist cinematic wave. However, as Kaplan argues,

It is this persistent presentation of the masculine position that feminist film critics have demonstrated in their analysis of Hollywood films. Dominant, Hollywood cinema, they show, is constructed according to the unconscious of patriarchy; film narratives are organized by means of a male-based language and discourse which parallels the language of the unconscious. (Kaplan 30)

critics point out that some self-proclaimed “feminist” films, despite their narrative themes of women’s self-growth or empowerment, remain limited to traditional male gaze structures. For example, in some works, the heroine must experience the frustration of heterosexual feelings, abandoned by men, or hurt before beginning to “self-discovery”; Or, despite being cast as roles with powerful forces, they still rely on men for emotional support and recognition. This apparent female independence continues the narrative logic of a patriarchal structure and belongs to a “feminism packaged by men’s gaze.” However, in Portrait of a Lady on Fire, Sciamma manages to break away from the traditional shackles of male gaze structure by establishing a female agency. The three female characters in the film – Marianne, Héloïse and Sophie – each fight against society and male power in different ways. At the beginning of the film, Marianne learns from the maid Sophie that Héloïse’s sister has chosen to jump off a cliff to fight against a forced marriage. In the same way, Heloise resisted the fate of male gaze and possession in marriage by refusing to let many artists paint her portrait. Meanwhile, Sophie, a maid, chooses to have an abortion herself, accompanied and assisted by Marianne and Héloïse, after discovering her unplanned pregnancy – an act that symbolizes their collective courage to strive for autonomy over their body and their destiny. The film weaves together the experiences of the three women, showing empathy and cooperation among women, making “action” a collective force of resistance. What’s more, Sciamma also disintegrates the male viewing structure by redefining the power relationship of “gaze”. In the typical films of male gaze, women are often the object of the male gaze, passively reduced to “the object being watched.” In this film, however, Héloïse actively chooses to have Marianne paint herself – when she walks into Marianne’s room and sees a frame and chair, she is not forced to be a model, but sits confidently and lets herself be seen; More importantly, she responds to Marianne’s gaze by looking back, thus reconstructing the equal relationship between “watching and being watched.” At the end of the film, when they are about to leave, Héloïse calls Marianne to “look back at me,” urging Marianne to give her one final look, letting their time together transform into a memory that will remain forever in her heart. This gesture is not only an emotional call but a recapture of the right to gaze – she chooses to be seen, to turn that moment into an eternity of memory.Through this visual strategy of mutual subjectivity, Sciamma transforms women from passive “watched” to active “viewers,” achieving a complete transcendence of the narrative logic of male gaze.

(source:https://www.instagram.com/p/CIgGvTTj8Z1/?img_index=3)

Bell hooks once said in her book The Oppositional Gaze “ :

Looking relations within mainstream media are based on white supremacist patriarchy.” (bell hooks 118)

As social beings, we live in a society shaped by conformity: we observe and imitate the behaviors of those around us, and movies as the most popular forms of entertainment, naturally become embedded in our daily experience. Yet, “seen” and “happened” do not mean that they are reasonable or justified. For decades, the male gaze defines, shapes, and controls how we see, and ultimately, who we learn to value through popular media: depicting women as the source of men’s downfall, as individuals who only gain insight after being hurt by men, or as mothers whose love supposedly suffocates their children’s growth…. Men’s lack of self-control and emotional failure are easily displaced onto women, allowing male characters- and male audiences- to remain unaccountable.

As a result, stereotypical images of women continue to emerge on screens: sexy women who create trouble on the hero’s way to work, evil witches who curse the hero, female agents whose emotions supposedly compromise a mission… Under the “Mirror Theory” that applied to film, viewers adopt the male characters’ perspective, judging women alongside him, and unknowingly bring this bias into real life and even pass it on to the next generation. Much of this gendered bias seeps into us through unintentional, uncritical forms of viewing.

It wasn’t until the rise of feminist film that we realized that film could exist in this way; equal ways of seeing are, in fact, possible; and women need not be fragmented or sexualized through objectifying camera angles.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire reminds us to recognize the male gaze embedded in other films, and it urges us not to stop here, but to continue expecting, encouraging and demanding more– more diverse perspectives, more equitable ways of seeing, and more stories that resist the visual logic of patriarchy.

Annotated Bibliography

Corinn Columpar “The Gaze as Theoretical Touchstone: The Intersection of Film Studies, Feminist Theory, and Postcolonial Theory” 2002

Columpar argues that “the gaze” functions as theoretical tool that bridges film studies, feminist theory and postcolonial theory. She explores how the “ male gaze” (from Laura Mulvey’s psychoanalytic film theory) interacts with postcolonial concepts such as the colonial gaze and the ethnographic gaze :Men are active”lookers”; women are passive “objects of sight”. Cinema is complicit in patriarchy, offering “visual pleasure” through fetishization and voyeurism; Both objectify nonwhite bodies as primitive, authentic, and knowable. Cinema and anthropology served as tools of empire, producing “racial iconographies” that naturalized white superiority. Early films anf ethnographic photography(like Regnault’s West African studies) visualized racial hierarchy as “scientific evidence”. Finally, by using examples, Columpar concludes that feminist film theory must move beyond singular categories. Visuality is a site of intersecting power relations–gender, race, nation and class– that require hybrid frameworks.

I can use her argument supports how Celine Sciamma reclaims the gaze from patriarchal control and redefines it as reciprocal, ethical and emotionally mutual In “Portrait of a Lady on Fire.” By analyzing The Mutual Gaze, Absence of the Male Gaze, Slow cinematography and Symmetrical composition, Sciamma dismantle the “male gaze”, allowing women to look at—and understand—each other on equal terms, creating a truly feminist cinematic language of seeing and being seen.

Mulvey, Laura “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen, vol. 16, no. 3, 1975, pp. 6–18. https://web.english.upenn.edu/~cavitch/pdf-library/Mulvey_%20Visual%20Pleasure.pdf?

Laura Mulvey argues that mainstream cinema is structured by a “male gaze” that positions women as objects of visual pleasure and men as active subjects of looking. Drawing on psychoanalysis, she explains how film reinforces patriarchal power by aligning spectators with the male protagonist’s controlling gaze, creating visual pleasure through voyeurismand fetishization of the female body. Mulvey calls for a new, feminist cinema that resists these conventions and challenges dominant ways of seeing.

I can use this theory to explain how Sciamma creates a mutual gaze, placing women as both subject and viewer, breaking the imbalance in traditional power distribution in which men are the inspectors and women are the objects of looking. Her work can be quoted when I illustrate the scene where Héloïse says to Marianne, “We are both looking at each other,” instead of Marianne simply staring at her. At the same time, in the scene where the three female sit side by side at the dining table, evenly dividing the frame into three parts, the film also subverts the traditional male gaze by rejecting the manipulative and objectifying camera angles often used on women in classical cinema.

Hooks, Bell. “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.” Black Looks: Race and Representation, South End Press, 1992, pp. 115–131.

In this chapter, bell hooks argues oppositional gaze as a critical resistant form of looking developed by Black women in response to their historical exclusion and misrepresentation in the White-people dominated- mainstream cinema. She points out that the Hollywood visual regime relies on white, patriarchal structures that deny Black women identification and pleasure, making critical spectatorship a political act.

By reclaiming the right to look—and to look back—Black female viewers challenge the racialized power embedded in filmic images and narrative norms.

I can use her work as a reference to emphasize how looking (“gaze”) can function as an establishment of power, making Black women viewers feel a sense of discomfort while watching those films. Also, according to hooks’ work, she realizes that the reason some Black women can accept those films is because they force themselves not to think too deeply. I want to use this as a strong argument to remind readers that “it is happening, don’t think too much” isn’t a real way to resist inequalities in male-gazed (or white-gazed) cinema. Instead, we must call for more films that place women in an equal position to other characters and stop letting patriarchal structures in film reshape our thoughts。

Kaplan, E.Ann. Women and Film: Both Sides of the Camera. Methuen. Routledge, 1983 pp24-36

Kaplan traces the evolution of feminist approaches to cinema–from early sociological surveys to structuralist and psychoanalytic frameworks–and then applies these to detailed film analyses. She examines how the classical Hollywood apparatus positions women as passive objects of the male gaze, relegated to absence, silence and marginality, and how women filmmakers have attempted counter-codings, alternate cinematic practices and realist strategies. Kaplan also explores issues of production, distribution and the female filmmaker in the Third World, concluding that while feminist counter-cinema holds promise, institutional constraints and patriarchal structures continue to limit its reach.

I can use Kaplan’s work to show how the male gaze is so deeply embedded in the formal structure of cinema that even in the absence of male characters, the story setting, camera angles can still produce unequal gendered power relations. Her analysis helps clarify that these dynamics are not just produced by men on screen but are built into the cinematic language itself. This allows me to explain more clearly how Sciamma, in Portrait of a Lady on Fire, intentionally breaks away from these embedded constraints and constructs a visual world where women are positioned as subjects rather than objects of the gaze.

Sciamma, Céline. “Céline Sciamma: ‘It’s a Manifesto About the Female Gaze.’” Little White Lies, 2019.

Sciamma, Céline. “Portrait of a Lady on Fire Director Céline Sciamma on the Film’s Radical, Subversive Love Story.” Vox, 2020.