note: sorry the format is a little weird, it got messed up when I pasted it from google docs

this is a link to the song: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t1Jm5epJr10

John Lennon’s Revenge Against Meaning Mongers

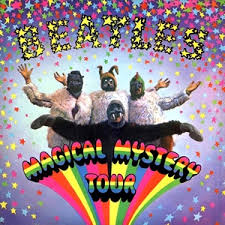

In 1967 The Beatles released “I Am The Walrus” on the Magical Mystery Tour Album and television film. As strange as it sounds, the first verse of “I Am The Walrus” contains some of the tamest lyrics in the whole song:

I am he as you are he as you are me

And we are all together

See how they run like pigs from a gun

See how they fly, I’m cryin’ (The Beatles).

As the song continues it delves into stranger and stranger territory, mentioning “Crabalocker fishwife, pornographic priestess” and “Semolina pilchard / climbing up the Eiffel Tower” culminating in an outro that includes a dramatic reading of Shakespeare’s King Lear. The Beatles were at the peak of their career following the release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Revolver. Simultaneously Susan Sontag published an essay titled “Against Interpretation” in which she asserts that it is problematic for society to assume that the value of art lies within its meaning. She disagrees with the practice of interpreting art as an intellectual experience that prescribes explanatory vocabulary, rather art should be a sensory experience where prescriptive language is used to describe an individual’s experience with the art (Sontag 8). Susan Sontag’s Against Interpretation argument is exemplified by “I Am the Walrus” by The Beatles which speaks specifically to her point of interpreting art descriptively rather than prescriptively, and the obsessive act of searching for meaning in art.

In “Against Interpretation” Sontag doesn’t declare that all forms of interpretation are problematic, she finds an issue with the particular instance of interpretation when it is done to search for meaning or representation. Sontag argues that “To interpret is to impoverish, to deplete the world—in order to set up a shadow world of “meanings” (4). More simply, Sontag says that prescribing everything a meaning removes the individual experience of attempting to understand what something means to you by putting that into words or coherent thoughts rather than just emotions. One might argue: “But isn’t it the human condition to find meaning in even the most arbitrarily assembled words and sounds?” (Zimmer). Sontag doesn’t wholly disagree with this argument. More so, she believes that within this somewhat innate urge to understand art, we (the general public) should avoid using absolute meanings for art pieces and instead describe on an individual level the sensory experience we had with the art. She further explains how interpretation diminishes art: “Interpretation amounts to the philistine refusal to leave the work of art alone. Real art has the capacity to make us nervous. By reducing the work of art to its content and then interpreting that, one tames the work of art. Interpretation makes art manageable, conformable” (Sontag 5). The Beatles’ discography is a perfect example of making art more easily digestible. Around 1965 George Harrison and John Lennon started to use LSD, which influenced their music and resulted in very psychedelic songs. At the time this sound was new, uncomfortable, and sort of taboo. Society’s way of making this new music more of a comfortable experience was to start to analyze the meaning of lyrics that were written while Harrison and Lennon were under the influence of a hallucinogen.

Applying Sontag’s argument to this example, this effort to interpret lyrics purely because they might cause feelings of discomfort is pointless and is actually detracting from the experience of the music.

Though music, just like any other form of art, is shared with the public to enjoy as they wish it can still be disheartening to hear that the music is being enjoyed in a way different than what was intended or imagined. Sontag notes that “It doesn’t matter whether artists intend, or don’t intend, for their works to be interpreted” (6). Creating art has morphed into a different experience where artists are unknowingly relinquishing the control of their work for interpretation instead of for enjoyment and to add to culture. The story of “I Am The Walrus” is a perfect example of that, even though The Beatles released music for a plethora of reasons other than interpretation that is what ended up happening. Following the release of “I Am The Walrus” John Lennon did several interviews where he explained he had discovered “fans were analyzing lyrics of The Beatles’ songs. More specifically, Lennon had read a letter from a student from his alma mater, Quarry Bank High School for Boys, that said the literature classes were studying the meaning of The Beatles lyrics” (Walthall). Just as Sontag said it didn’t matter whether John Lennon or The Beatles wanted or intended for their work to be interpreted, it happened anyway. It was just chance that led to The Beatles discovering that their lyrics were being analyzed at such an extreme level. In 1968 when George Harrison spoke with Hunter Davies, The Beatles biographer, he discussed how “the first line of ‘I Am the Walrus’ was a good example of people taking the Beatles too seriously…. ‘People looked for all sorts of hidden meanings. It’s serious and it’s not serious’” (Zimmer). Even when the song was purposely nonsensical as a direct response to looking for meaning in Beatles song lyrics, people still tried to decipher every single word. As Sontag argues, this extreme desperation to find meaning within art distances us from enjoying the art itself (9). Instead of listening to the song for the sake of pleasure, it becomes an intellectual chore. This intellectual chore is exactly what Sontag wishes for society to avoid instead she wants society to enjoy art as an individual sensory experience and find individual meaning front the experience with the art.

The main intentions of The Beatles releasing music were for entertainment purposes and to add to culture, not to have people analyze the meaning behind every one of their songs. However, this did not dissuade fans from doing so. Zimmer notes how Paul McCartney made a “strike against meaning-mongers, in his introduction to Lennon’s In His Own Write. ‘There are bound to be thickheads who will wonder why some of it doesn’t make sense, and others who will search for hidden meanings,’ McCartney wrote. ‘None of it has to make sense and if it seems funny then that’s enough’”. The phrase that Zimmer uses “meaning monger” is an extremely apt description of people who interpret art. Particularly because a monger is defined as having a petty and discreditable nature. There is no great importance to searching for the meaning behind every last lyric of a song. The importance lies within the individual sensory experience one has with hearing the music or seeing a painting in a museum. In her essay Sontag declares, “Interpretation is the revenge of the intellect upon art” (4). Just as a monger is petty and discreditable, so is revenge. Sontag deeply believes that interpretation decreases the value of art and culture, when people are so focused on trying to understand what someone wants them to understand or is trying to tell them they miss finding their own meaning. It is an undeniable fact that “‘I Am The Walrus’ is nonsense. But it was designed to be so, and craftily at that” (Walthall). Later in the article Walthall expands on that idea and says “Lennon decided to pen a song so obscure and so bizarre that the meaning would be impossible to discover”. Writing such an eccentric song with almost unintelligible lyrics was extremely calculated and well thought out. “I Am the Walrus” is John Lennon exacting his revenge upon the intellect.

John Lennon’s frustration and disbelief after learning that Beatles lyrics were being analyzed at his former school resulted in him writing the strange and fantastical “I Am The Walrus”. That situation embodies the thesis of Susan Sontag’s argument: reducing a piece of art down to its meaning cheapens art as a whole and prescribing a work of art a singular meaning is a practice that we need to move away from and towards describing the individual experience.

As much as Sontag’s argument still stands today, it can also be said that there has been a big shift in modern music culture. It could be argued that music that is being currently released doesn’t affect culture anywhere to the extent of The Beatles, thus there is less of an inclination to interpret lyrics and understand them on a deeper level. The music of today is specifically released to be palatable to the public, with many songs sounding extremely similar or following the same chord progressions. Since the public feels comfortable listening to these songs, there isn’t the desire to reduce the art to just its meaning in search of a more agreeable experience, that’s already done.