On a day in 1963, a unique performance took place at the Pocket Theater in New York. The ticket price of the performance was determined by the duration of the audience’s endurance: the longer they persisted, the greater the amount they received in return when they walked out of the theater. This courage and perseverance-testing performance continued for a staggering 18 hours. This was the debut of Satie’s “Vexations.” The performance, which shocked the art world, was not only remarkably lengthy but also terrifyingly monotonous: a relentless 840-time repetition of just one single motif. Susan Sontag, in her essay “Against Interpretation,” challenges the prevalent approach of dissecting art for hidden meanings. In alignment with Sontag’s ideology, Erik Satie’s composition, “Vexations,” transcends the conventional paradigms of interpretation. This piece disrupts expected norms for art, emphasizes the inseparable nature of form and content, and triggers emotional responses, ultimately echoing Sontag’s call for a sensory and transparent experience of art.

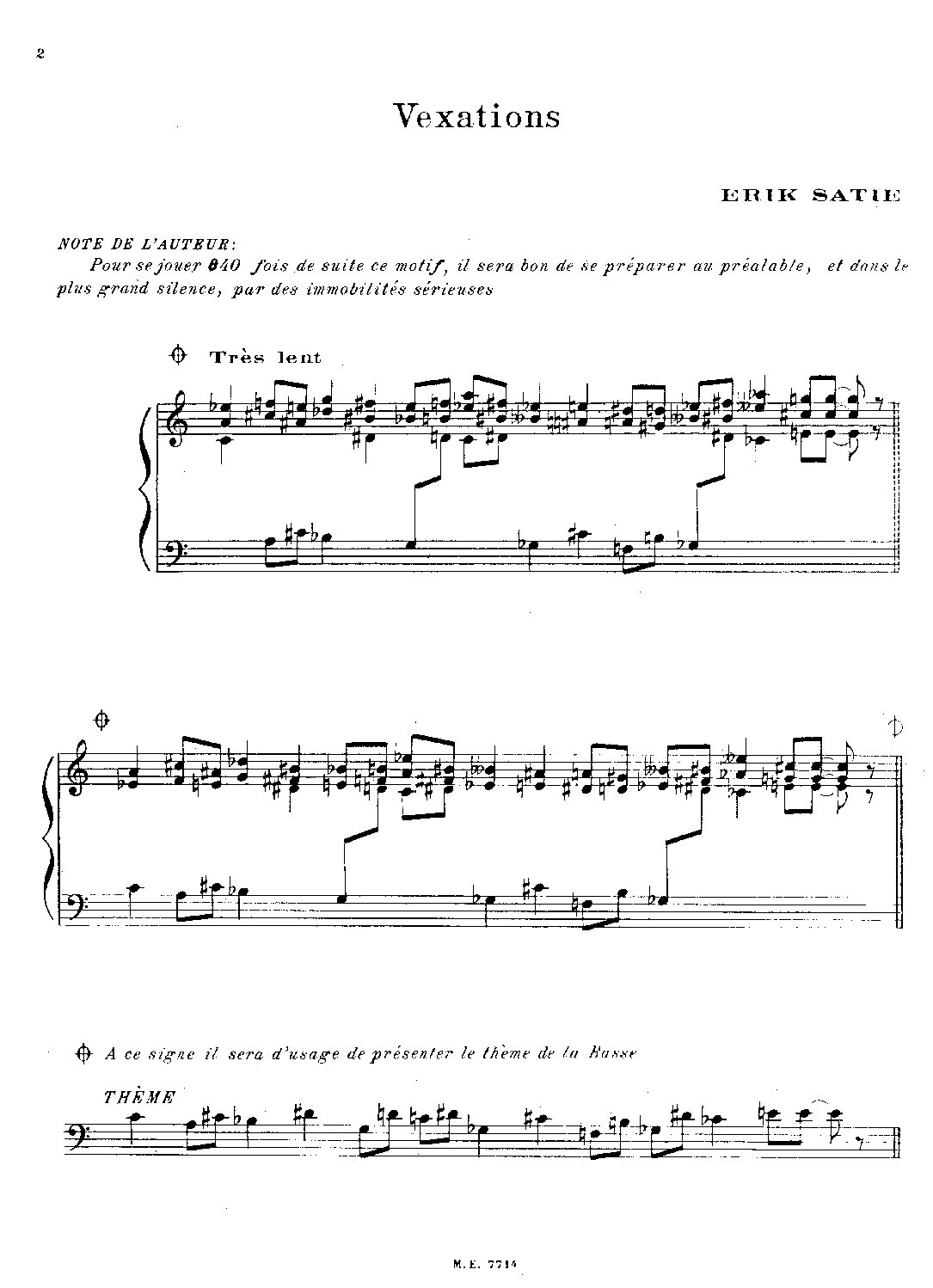

Satie’s artistic rebellion in this piece began with the manuscript itself. Initially, as people sorted out this music sheet from his cluttered room, no one expected that the performance of this unassuming score, which consists of just three lines, would be a test of endurance. The theme consists of 18 individual notes in the bass part, followed by two lines of harmonization as variations of the theme. The second variation just shifts the upper voices of the first variation down an octave, creating an opposing bass. A simplistic composition structure like this should not be the point of criticism; even the well-known “Canon in D Major” composed by Johann Pachelbel relies on repetitive motifs and variations. Yet, unlike the lyrical and melodic beauty of Pachelbel’s “Canon,” the sole motif in “Vexations” lacks any musicality. The combination of these 18 notes lacks melody and fluidity, and the harmonization is dissonant. Moreover, this piece does not include bar lines, time signatures, beats, tonality, or indications of volume—essential markings on any musical score. Despite being frugal with musical notations, Satie generously provided a performance suggestion.

There was a sentence mischievously written beneath the title: “Pour se jouer 840 fois de suite ce motif, il sera bon de se préparer au préalable, et dans le plus grand silence, par des immobilités sérieuses” (To play this motif 840 times in succession, it is better to prepare beforehand, and in the greatest silence, through serious immobilities.) From the performers’ perspective, this piece of advice seems like a prank orchestrated by Satie. As Susan Sontag suggested, a part of modern art appears in the public eye in the form of “abstract” or “parody” to exclude interpretation (7). “Vexations” is exactly that—Satie, in a composition style that goes way beyond established norms, creates a motif that is inherently indecipherable. This monotonous motif is not pleasant, not romantic, and does not make any sense. This piece, indeed, has been described by critics as a “parody” and even questioned by the public as not qualifying as music.

“Vexations,” just like its name suggests, incites vexation in both the performers and the audience. It’s a challenge to patience, an invitation sent from Satie, not for interpretation but for emotions and description. If the musician relay marathon premiere of 1963 only brought vexation to the performers, then what today’s pianists experience when challenging themselves to complete the entire performance solo is agony. According to pianist Nicolas Horvath’s description on his YouTube channel, he recalls the 28-hour performance as consisting of three stages: “Pain starts past 6 hours; Madness starts past 12 hours; Hell starts past 20 hours!” Survivors among the audience who endured the concert share similar sentiments: New York Times journalist Joshua Barone, reflecting on his experience of listening to the 19-hour performance of “Vexations,” used words like “hallucination” and “delirious” to describe his mental state but also mentioned that he was “left with the best hearing” he ever had (Barone). Looking at the reviews of the brave warriors who survived the hard fight, their narratives, without exception, are not interpretations but descriptions. For the performers, they stepped onto the stage with pressure and ambition, and in the process of 15-28 hours of performance, they grappled with self-doubt, fear, furor, and devastation. Ultimately, they reached an indescribable state of extreme emptiness and mesmerization. As for the audience, many attended concerts with curiosity and a desire to decipher the meaning of Satie’s eccentric work. In the process, they went through tiredness, indignation, and hallucination. In the end, some even forgot the repeated motif, purely engaging their auditory and sensory perceptions and listening to each bare note with sheer sensation. It achieves what Susan Sontag advocates as “the most liberating value in art”—transparence (9). The performance of “Vexations,” through this extreme approach, gradually steers individuals away from using intellect to judge and interpret. No one can walk out of the music hall after a 20-hour performance and still reminisce and ponder on Satie’s intent in composing this piece or the content conveyed by the composition. This temporary detachment from intellectual labor prompts people to perceive music in the most primal way, allowing the brain to take a break while engaging the senses actively.

Unlike other art pieces, which are immediately dissected and extracted for their main content by modern artistic “surgeons,” “Vexations” is challenging to be dissected. The 840 repetitions constitute the content of “Vexations.” In other words, the form and content of “Vexations,” by nature, are inseparable. This integration and ambiguity prevent a direct connection to a specific meaning and interpretation, encouraging the audience to abandon the notion of deciphering the meaning and instead consider a broader picture beyond the piece. As typical Dadaist artists, Erik Satie, along with renowned Marcel Duchamp and John Cage, engaged in avant-garde and experimental creations. They opposed rationality, rules, and traditional forms of art, even challenging any existing forms. John Cage, a staunch supporter and ally of Satie, showcased a striking similarity between his work 4’33” and Satie’s “Vexations.” The performance of 4’33” can be carried out by anyone without the use of any instruments: the performer simply sits on stage, making no sound, leaving the four minutes and thirty-three seconds entirely to the audience. The sounds in the audience become the entirety of the content of 4’33.” Just like Satie’s “Vexations,” the performance creates its content in the process, or one could say that the form of this performance is its content. If the contemporary dismantling of artistic forms and contents can be acceptable, avant-garde figures like Erik Satie and John Cage should not be condemned to be at the other end of the spectrum. By emphasizing that form constitutes content, they highlight the inseparability and equal importance of form and content. Just as Susan Sontag mentions in her essay, we should not crudely separate form and content and assign vastly different weights to them (2). Form and content are inherently interconnected. In a society dominated by rampant materialism, the act of separating form and content is gradually evolving into a human intuition. The works of Satie and similar artists, however, pull people out of familiar comfort zones, prompting them to contemplate what they originally expected from art.

Satie’s “Vexations” aligns with Dadaism but starkly contrasts with Wagnerism. The term Wagnerism is associated with the ideas and works of Richard Wagner, a 19th-century German composer known for incorporating complex orchestrations and political elements into his grand operas. For example, in his epic masterpiece “The Ring Cycle,” he weaved patriotism and political ideology. This integration of political context elevates Wagner to the music pedestal. While Satie intentionally emulates Richard Wagner’s use of thematic repetition and endless chord progressions in “Vexations,” he creates a minimalistic musical form consisting of Wagnerian characteristics. In “Vexations,” he achieves auditory simplicity and reduces decipherable elements to a minimum, separating his composition from any political or specific content. Critics, especially Wagner enthusiasts, may question “Vexations” for its value and qualification as music. However, the eccentricity and simplicity in Satie’s composition should not diminish his work any less of music, while the grandeur and complexity in Wagner’s composition should not elevate his work any more of music. The discrepancy in how the public perceives Satie’s and Wagner’s works does not originate from the distinction between the two artists but comes from the discrepancy between what society expects from art and what the work of art really is. Sontag’s assertion about living in a society with a “hypertrophy of the intellect” resonates here (4). The essence of art has not undergone significant changes, but the societal emphasis relentlessly headed to utility and efficiency, resulting in the overemphasis on content and intellect. Satie and Wagner’s difference is not musical but social—the former’s deviation from contemporary societal ideals contrasts sharply with the latter’s alignment with them, creating a dramatic discrepancy.

What Erik Satie and other experimental artists achieved through their artwork was akin to setting a table for eagerly awaited diners. Knowing the audience’s impatience to feast on messages and meanings, they presented the dish, lifted the jar, and to everyone’s surprise—there was only an empty plate. Art is like a course of dish, and contemporary people tend to view artistic forms as mere plates for holding content. People devour and gorge on the content while considering the container unimportant and disposable. But if art serves solely as the vessel of content, there is no need or reason for different artistic forms to exist; to fulfill the highest efficiency that modern society pursues, information and content can be expressed in the most straightforward language instead of in dazzling artistic forms. In his playful way, Erik Satie left the startled audience to rethink carefully why they needed art and what they expected to gain through art.

Works Cited

Barone, Joshua. “What It’s Like to Hear the Same Piece of Music for 19 Hours.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 29 Sept. 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/09/29/arts/music/erik-satie-vexations-guggenheim-museum.html.

Erik, Satie. “Vexations.” Paris: Max Eschig, 1969. Plate M.E. 7714.

Sontag, Susan. “Against Interpretation.” Against Interpretation, Picador, 1966, pp. 2-9.

“Satie Vexations Complete Non-Stop Performance (9.41 Hours).” Performance by Nicolas Horvath, YouTube, YouTube, 1 July 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gImDzmNuEDA. Accessed 24 Oct. 2023.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.