By Flora Georgianna.

Nearly everyone has seen a photo claiming to capture a ghost, spirit, or proof of life after death. Skeptics jump to disprove them and believers consider them evidence of the supernatural. But the man who popularized spirit photography was neither a skeptic nor a believer. He was a conman playing on emotional vulnerability.

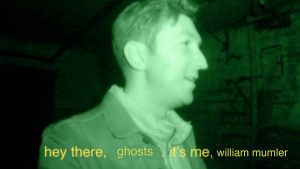

William Mumler was an amateur photographer working in Boston. At the end of the Civil War, he claimed to have captured a photograph of his deceased cousin. As the news of the image spread, Mumler had no shortage of clients willing to shell out for photographs of them with their deceased relatives, many of whom had recently died in the Civil War. Mumler even famously photographed the widow Mary Todd with Abraham Lincoln’s ghost placing his hands on her shoulders. Since no one knew the intricacies of the brand-new camera, invented only 20 years prior, to explain it, much of the general public considered the conman’s photos legitimate. Today, they have been attributed to straightforward photography techniques both while the shutter was open and in editing.

William Mumler was an amateur photographer working in Boston. At the end of the Civil War, he claimed to have captured a photograph of his deceased cousin. As the news of the image spread, Mumler had no shortage of clients willing to shell out for photographs of them with their deceased relatives, many of whom had recently died in the Civil War. Mumler even famously photographed the widow Mary Todd with Abraham Lincoln’s ghost placing his hands on her shoulders. Since no one knew the intricacies of the brand-new camera, invented only 20 years prior, to explain it, much of the general public considered the conman’s photos legitimate. Today, they have been attributed to straightforward photography techniques both while the shutter was open and in editing.

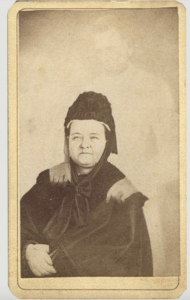

Mumler figured out new ways of altering a photo while the pinhole shutter was open. In the early-mid 1800s, Joseph Nicefore and Louis Daguerre discovered that projecting light onto a coated metal plate would “burn” an image into the surface where the light hit it onto metal, glass, or another surface. Since the shutter of an antique camera needed to be very small to make the image bright enough, it had to be open for an extended time (between 20 seconds and 20 minutes), long enough for a person to move in and out of the frame. When Mumler had a friend walk in and out of the frame while the shutter was open, their presence was blurred to a translucent, ghostly shape. Mumler also took old photographs printed on glass and placed them in the camera to superimpose the prior image onto the photograph currently being taken. He could also block the light or overexpose certain parts of the image to add shadows or bright spots, which is called dodging and burning. With precision, this could resemble a shadow or a hazy figure which could be seen as a ghost.

Although people approached Daguerreotype photography with apprehension, Mumler knew how to manipulate his customers into trusting him and his technology. Many reacted to the camera’s invention with suspicion or even fear, since being able to capture life in a static image had never been done like this before. Many early photographers eased these fears by photographing the American elite like President Lincoln. Although the camera’s supposed ability to capture ghosts alarmed people even more, Mumler built credibility and trust with his clients through an extensive portfolio and a good reputation, allowing him to profit off of their trust in him and his skills.

A newfound belief in life after death called Spiritualism also helped make Mumler a rich man. Spiritualism first rose to popularity in 1848 when two preteen sisters claimed to be communicating with a ghost in their New York home. The Fox sisters knocked on the walls and would interpret the knocks in return as being the response of a ghost. Their claims began the unconventional movement, stressing not only the existence of life after death but the ability and desire of the dead to communicate with the living. Spiritualism gained popularity fast, as author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and other intellectuals even endorsed it, mainly because it offered solace to its followers. The human mind tends to believe that which comforts it, and many found the existence of an afterlife comforting.

Mumler also played on his clients’ grief. Considering the violent ends of the approximately 620,000 people who died during the Civil War, mourning families were desperate to find any source of closure with their loved ones. Mumler’s photographs provided his clients with a sense that the deceased remained with them and were no longer hurting from painful battlefield deaths. In reality, these loved ones were well-placed shadows or the superimposed image of one of Mumler’s former subjects.

Despite how many people have disproved Mumler’s spirit photography and ghosts, the early twenty-first century saw a modern revival of fascination with the paranormal, most significantly in media. The genre of ghost movies exploded in the second half of the 20th century and modern inventions allow for high-tech paranormal investigation. Hit series Ghost Adventures and Buzzfeed Unsolved have validated the use of electromagnetic field readers, radio scanners, thermal cameras, and motion sensors, just as Mumler used photo alteration, to give “evidence” of the lingering of the human spirit.

Let us not forget that Mumler profited off of mourning families. His greed tainted whatever comfort he provided them with a memory of a loved one or the affirmation of an afterlife. William Mumler was a photo-editing fraud who only succeeded because his deception was timed well to exploit misunderstandings of the new camera and mourning after the Civil War.