By E.D.

Edgar Allan Poe wrote a lot of poetry about water. He wrote about the sea, the ocean, lakes and rivers and streams, and he wrote about it all with a high regard even close to fear. Eight of Poe’s seventeen most famous poems not only reference, but revere, great bodies of water. Water symbolizes many things in his poetry, but more than anything it indicates a nineteenth century relationship to the sea, a relationship defined by mystery and danger and conquest.

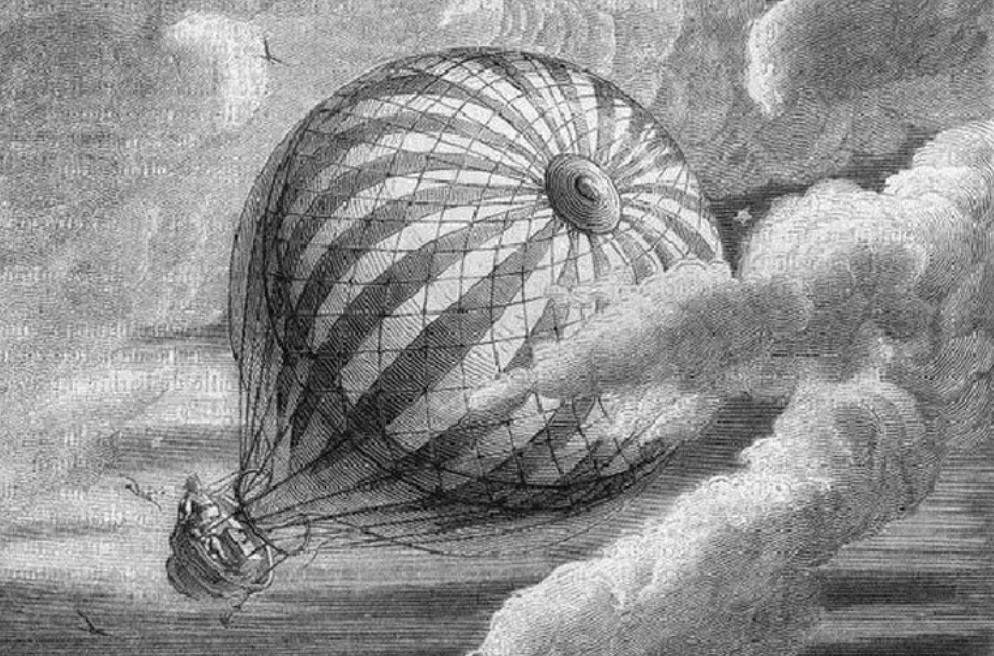

Just like water flows rapidly through a coursing river, the story of a gas balloon crossing the Atlantic Ocean in just three days flowed very quickly downstream to the great excitement of the general public. The newspaper article in the New York Sun, published on April 13, 1844, tells a vivid story of Mr. Monck Mason’s journey from London, England, to Charleston, South Carolina, in his gas balloon named Victoria. The article exclaimed the greatness of such a feat for conquering the mysterious danger of the ocean, saying, “the air, as well as the earth and the ocean, has been subdued by science, and will become a common and convenient highway for mankind … The Atlantic has been actually crossed in a balloon … and in the inconceivably brief period of 75 hours from shore to shore!”

However exciting, this account seemed a little fishy from the start. It was actually written by water-reverer Edgar Allan Poe himself, who had just moved to New York City and hoped to promote himself in the journalistic scene by spreading a beautifully imagined and gracefully written hoax about Mr. Mason Monck’s fantastical balloon journey. While Monck Mason was, in fact, a real person who did balloon from London to Germany in 1836, he did not balloon across the Atlantic Ocean, and he definitely did not do it in three days. It wasn’t until 1919 that a dirigible successfully crossed the Atlantic Ocean, and it took almost five days.

Many people have devised reasons for Poe’s hoax. Just as we have to interpret his poetry, it seems we also have to elucidate the meaning of his more “serious” work. Some say it was Poe’s attempt at one-upping Richard Adams Locke’s 1835 moon hoax, which Poe claims Locke plagiarized from his own moon hoax written two months prior. Others say that Poe simply loved hoaxes and enjoyed the chaos and excitement of the days when his published hoaxes reached his desired audience by way of the newspapers.

And reach his desired audience this hoax did. Poe later told the newspaper Columbia Spy, “on the morning (Saturday) of its announcement, the whole square surrounding the Sun building was literally besieged, blocked up from a period soon after sunrise until about two o’clock PM … I never witnessed more intense excitement to get possession of a newspaper.” In the chaos of the day, New Yorkers were buying copies of The Sun for up to fifty cents each, the equivalent of fifteen dollars today.

But Poe claimed that he never received a cent of The Sun’s massive profit from this hoax story (1). Two days after its publication, The Sun issued a correction for the article, and acknowledged the erroneous nature of the balloon hoax story. It didn’t matter much for them, they had already collected their profit. It did matter for Poe, though. In his attempt to promote his name in the newspaper world of New York City, he only succeeded in damaging his reputation as a journalist, solidifying his fate as a poet forever.

It also mattered for the readers of the hoax. Why was The Sun’s audience so quick to play on the shores of the hoax-infested waters? It seems that the general public of New York City and beyond were in a hurry to hear an amazing, fantastical story of a balloon conquering the dangers of the Atlantic Ocean and innovating a new mode of transportation of the future. To the average reader, the story may have represented a triumph over the banality of a mediocre life. It signaled the start of a new world in which every person could afford the privilege to dream. Perhaps it didn’t even matter to these people that the story turned out to be a hoax; it was enough to believe it could have been true.

Fake news, hoaxes, white lies, plagiarism: they’re all the same to an audience of ordinary dreamers. This fictitious story wasn’t inherently harmful, instead it was engaging and poetic. Poe concluded his story of Mr. Monck Mason’s gas balloon journey by saying that “this is unquestionably the most stupendous, the most interesting, and the most important undertaking, ever accomplished or even attempted by man. What magnificent events may ensue, it would be useless now to think of determining.” With a conclusion like that, it is hard not to feel inspired and encouraged about the future.

Perhaps news, even fake news, can inspire. It certainly can distract people from their occasionally unfortunate realities. If this particular hoax solidified Poe’s career as a poet, then it wasn’t pointless. If this fantastically false piece of news inspired Jules Verne’s classic novel, Around the World in Eighty Days, as some believe, then this fiction actually contributed to the world’s beauty. Perhaps it is just our human nature to romanticize the events, including the fake news, of the past. But perhaps there really is some value in harmless fake news.

- Goodman, Matthew. The Sun and the Moon, 2008.