By Flora Georgianna

The assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is submerged in controversy. The convicted killer James Earl Ray claimed his innocence in prison. King’s friends and family even supported this. They believed that King’s death was the responsibility of a greater power than just a lone shooter, accusing the FBI and the Justice Department of being responsible for the Civil Rights leader’s death. Although there is no strong evidence that Ray was not the assassin, the King family’s accusations exist within the context of a broader conspiracy. The government had wiretapped and surveilled King, his fellow Civil Rights leaders, and anyone who posed a threat to the stability of the United States government and its racist institutions. Thus, the social and political context surrounding King’s assassination has allowed for this conspiracy, without strong evidence, to spread.

On April 4, 1968, Dr. King Jr. was shot and killed in Memphis, Tennessee. The official consensus is that James Earl Ray acted alone in the assassination. He had rented a room across the street from King’s motel, his fingerprints had been lifted off the rifle, and the white nationalist had a clear motive to kill the leader of the Civil Rights movement. Ray even confessed to the murder after his arrest.

Sitting in prison, however, Ray recanted the confession, insisting that at various times that he was acting on the orders of a man named Raoul (who was never identified or caught), that a local shopkeeper was involved, and that the assassination was a setup. While inmates with life sentences often retract their confessions, Ray found some unlikely allies among the King family and their friends. In 1997, after five investigations, Ray was dying of liver disease and Hepatitis C complications, and the inmate called King’s family. Dexter, the youngest son of Dr. King, told Ray that his family and many other prominent civil rights activists believed Ray’s claims of innocence.

Ray possibly lied when he recanted his confession. His descriptions of the assassination and Raoul or others involved in a setup vary. Furthermore, no potential co-conspirators or alternative perpetrators have ever been identified. Because Ray was serving a life sentence, any evidence proving his innocence could have meant his release from prison. Why then did the King family and friends believe that Ray was innocent? Although they never named an alternative assassin, Coretta Scott King argued that “local, state, and federal government agencies were deeply involved in the assassination” of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

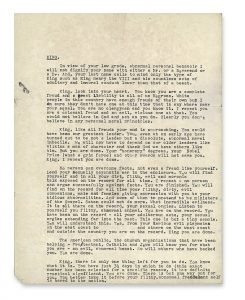

The King family had reason to believe that the government was involved in the assassination. The Federal Bureau of Investigation had wiretapped King’s home, offices, and hotel rooms before his assassination, looking to gather information on associations with the Communist party. Instead, they found blackmail material: evidence of King’s unpastoral sexual conduct. King received threatening letters full of racist attacks and intimate knowledge of his extramarital affairs, explicit enough to harm his reputation. Many of these letters ended in threats to King’s safety or life. Dr. King and his family wholeheartedly believed that former FBI director J. Edgar Hoover sent these notes. It was no secret that Hoover and his department despised King, claiming that he was a threat to national security. In short, the family’s paranoia was warranted.

The King family had reason to believe that the government was involved in the assassination. The Federal Bureau of Investigation had wiretapped King’s home, offices, and hotel rooms before his assassination, looking to gather information on associations with the Communist party. Instead, they found blackmail material: evidence of King’s unpastoral sexual conduct. King received threatening letters full of racist attacks and intimate knowledge of his extramarital affairs, explicit enough to harm his reputation. Many of these letters ended in threats to King’s safety or life. Dr. King and his family wholeheartedly believed that former FBI director J. Edgar Hoover sent these notes. It was no secret that Hoover and his department despised King, claiming that he was a threat to national security. In short, the family’s paranoia was warranted.

Yet the FBI’s animosity towards Black social leaders extended farther and deadlier. Just a year after Dr. King’s death, the Chicago Police Department assassinated Black Panther Party leaders Fred Hampton and Mark Clark. The Federal Bureau of Investigation had planted someone into Hampton’s professional circles to deliberately drug him, then tipped off the Chicago Police Department, murdered the two leaders in a raid of Hampton’s west-side apartment. When documents detailing the federal government’s involvement were uncovered, the victims’ families sued for violation of civil rights and obstruction of the judicial process.

Conspiratorial beliefs have long prospered in minority communities threatened by the United States government, and for legitimate reasons. Black filmmaker Spike Lee once said, “There are many other examples if we go down the line, where stuff like [Katrina and Tuskegee Experiments} happened to African-American people. I don’t put anything past the American Government when it comes to people of color in this country.” Simply put, the government’s treatment of minority communities has created distrust in the government. According to political scientists Joseph Uscinksi and Joseph Parent, people belonging to groups that are out of power are more likely to create and believe conspiracy theories about their oppressors. This is a form of coping with oppression, and in the Civil Rights era, systematic racism rightfully made King and his family suspicious and made the FBI’s attacks on King and other Civil Rights leaders seem to be more plausible.

While the Federal Bureau of Investigation may not have pulled the trigger or orchestrated the details of King’s assassination, they are far from innocent because of their repeated threats to King’s life. His family’s lack of faith in the U.S. Justice Department was founded in the government’s racist institutions and the FBI’s history of illegal surveillance. James Earl Ray very likely assassinated Dr. King, acting alone and on his own free will. Yet, the Federal Government was responsible for invading Dr. King’s privacy, illegally surveilling him, and blackmailing him. What many believe to be an unfounded conspiracy theory has been justified by social and political context.