Interviews

Welcome to the audio guide page! Below are recordings from interviews with 3 different Smith art professors who have work in the collection. You can also see images of the art they reference in their interviews, including their own work. Please feel free to comment your responses to the questions after each interview and see what others think–I would love to know your thoughts.

Lynne Yamamoto on Preparatory Drawing for Home

Transcript

Yamamoto: I’ve lived in western Massachusetts for over 20 years now, and my research, as well as my immediate family, except for my partner, live in Hawaii. And so, um, I literally travel there twice a year, but I very often travel there in my mind also. And so, um, I literally travel there twice a year, but I very often travel there in my mind also. Um, and when I made this piece, I was thinking that perhaps I needed to remind myself that I, I’m at home here. You know, that I, I spend most of my year here. And that’s how the piece originated, was to speak to being rooted in Western Mass. But it is oriented so when you stand in front of it, you’re literally looking towards Hawaii, if you made that arc. And I felt it really expressed well the situation of being physically rooted somewhere and paying attention to that, but the reality of sometimes thinking about other–another home, or other homes that have been meaningful to you. That’s kind of what inspired the piece.

Eva: Cool. Thank you. Um, and how did this preparatory drawing fit into all of that?

Yamamoto: Well, I was proposing it for the biennial at Park Hill Orchard, the sculpture biennial, and you need to provide visuals (laughs) so I created these. I love watercolor and gouache, and I love simplicity. And I also make things that are either ephemeral, or they take up a lot of space, and so sometimes I can’t physically make something until I have a venue for it. So I do–I do a fair number of these kinds of preparatory drawings. Um, I happen to really enjoy doing these, um, because, you know, it’s really beautiful when an idea pops into your head and it’s, it’s almost effortless, considering most ideas or most projects I have don’t have that kind of genesis, and this happened to be very– I had a lot of clarity around this, this piece, um, down to, you know, it being in the language of a gravestone. Um, I didn’t mean it in a morbid sense at all, but, um, I just felt that they speak to memory. They’re in a language of remembering. I wanted the finished piece to be made of Vermont marble as well, so…so the stone would come from, you know, around here.

I think when people think of artworks that are, um, outdoors, and I think in the sort of tradition of this biennial, they’re very often really large scale. They’re, um, you know, and I really respect that. They’re, they’re very large and they’re very prominent, and I wanted to make something that you had to really find, and pay attention to, and spend time with, to let the meaning of it unfold for you. So my piece was rather different than most of the others because it almost looked like it wasn’t there. Because from far away it just looked like grass (laughs) and you had to get very close to it. And it’s that way in the botanical garden. You know, you, if you don’t know where to look, you, you won’t find it.

See, Professor Petro, who teaches creative writing, asked me to talk to her class about this, this piece. And, um, this was in March, and it–there was still snow on the ground, and, um, you actually couldn’t see it. It was under a layer of ice, but we turned that into a, like, a kind of a, something serendipitous, because they could watch it as it gradually became more apparent as the, as the ice melted and the image then almost kind of rises to visibility. I really just, I admire artists who work in that way, who have a confidence, um, they don’t feel they have to make something monumental. They know what’s exciting to them and what they want to pay attention to, and they just practice that. And I really respect that kind of work.

I’ve loved working with students to put artworks both inside Hillier, but a lot of them have been outside of…you know, in the houses, in other buildings on the grounds. And, um, you know, after being at Smith all this time it was just, it felt very meaningful to kind of gift the peace to, to the land, essentially. It’s a way that, you know, even after I’ve left Smith, at some point I’ll look to this stone from where I, where I land, wherever I land.

In terms of where it lives now and I guess where it will live for a while, I hope, uh, I actually wanted people to bring their own thoughts and interpretations to it. Um. One of the reasons I just use the word home is that my hope is that it might provoke someone to reflect on what that means for them. Um, you know, when you see this marble slab with home on it embedded in the earth, um, someone might reflect on the way that they are… you know, I don’t know if they would think their home in Western Mass or not. What I hope is that someone can reflect on what’s complicated about home, you know, is it where you are? Is it where you are now? Is it the places you have called home? Is it a collection of all of it? Um, and how home is a kind of a dynamic and evolving concept for everyone. I, I felt that every student that comes to Smith makes a little bit of home for themselves here, or I, I hope they do in some fashion. And, um, but they’re…they’re still constantly tethered to the other place, the other places, you know, it might be in Massachusetts or other countries, but, um, I’m sure that their thoughts go to those other places as well.

My work deals a great deal with place and that place is…is Honolulu, or Hawaii generally. Um, but it’s, um, the experience of that place as a diasporic person of Japanese descent. In a lot of ways, that had to do with the mortality of my parents. I didn’t realize this at the time, but, um, one of the reasons I was interested in the pastness of Honolulu was that it was the past of my parents in some ways. Um, yeah, so my work in general deals with memory, um…family, um, ways in which materials or structures, especially architectural structures, streak o–speak of, um, a certain period in time, um, in Hawaii, my parents’ time there. Yeah, it’s a little hard for me to speak to in general terms because, uh, because my work is actually in, in flux right now. It’s like I’ve finished this big body of work for which what I just said is relevant, and I’m now….in a liminal space. I haven’t quite arrived at what my current practice is engaged with. I think it’s going to be different. It’s just very messy right now. I have about five different possible routes that my, my work could go.

Post your reaction to this art piece. What associations come up for you when you see the word “home” tucked away on a marble stone?

Katie Schneider on Inspiration, Artistic Values, and Why She Paints

Transcript

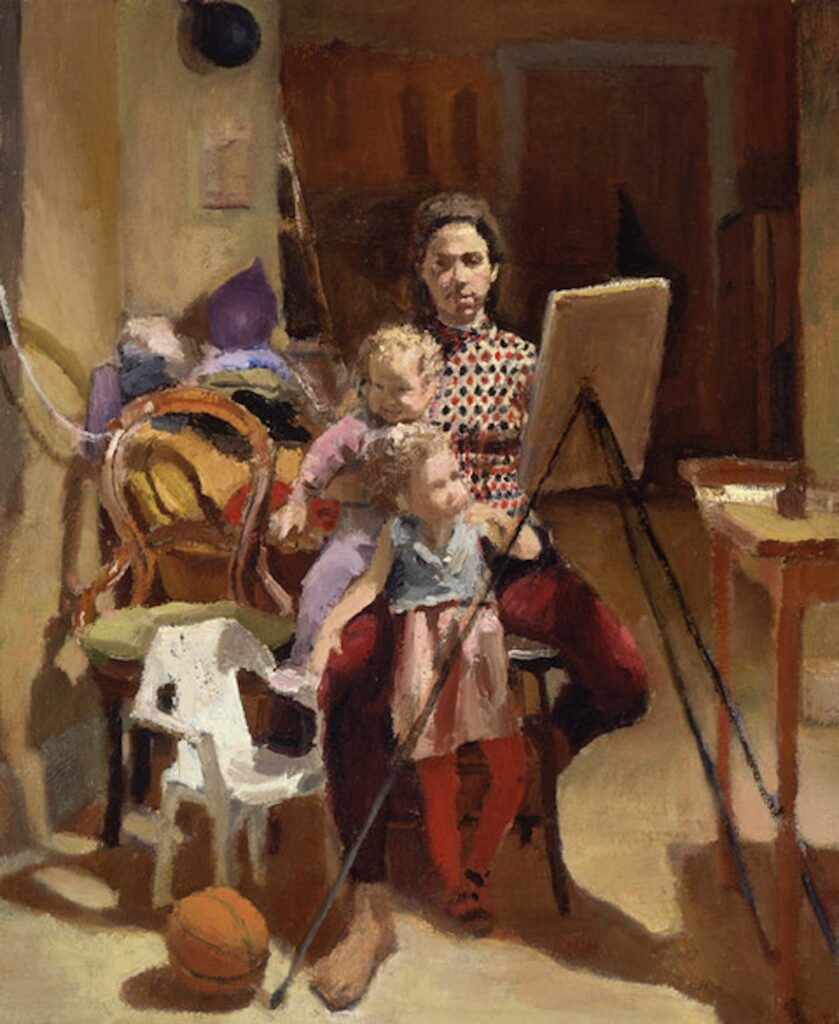

I grew up in a family of nine. There are seven kids in my family and I have a twin sister. And I guess it’s so familiar to be surrounded by faces, that was my landscape. I’m married to a landscape painter who grew up in Indiana, and he paints the landscape because that’s where he was most of the time. That was what he was aware of. And I guess I just really enjoyed, uh, I like people and I want them close to me. And so…I guess I’m always making them close to me by painting them (laughs). My objective as an artist is to be inclusive. I don’t want anybody to wonder why–what is this about? Why are they showing it to me? Like, I want them to come upon it and feel like I know that, and that speaks to me, and, um, it’s presented in a way that I haven’t seen it before, but it’s totally recognizable. So just elevating the mundane.

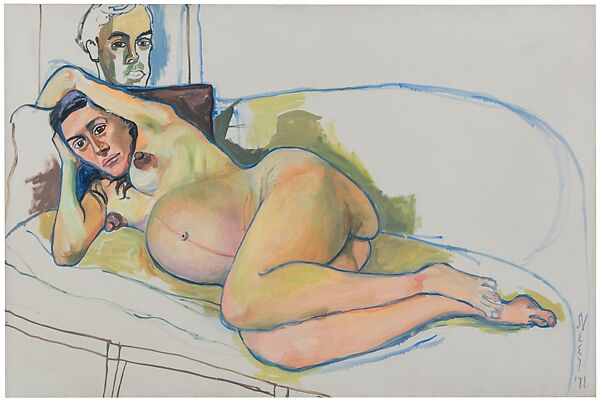

When I was pregnant, I was incredibly prolific because I knew there was a deadline. It’s like, I started them when I was already big. It was like, from eight months to nine months. And I did this three times, I have three children, so it’s funny to think like those three…maybe, you know, I didn’t get huge until I was probably eight months pregnant. So we’re talking really? Three, four months of my entire life. I painted so many paintings because, like I said, there was a deadline. And I loved the way I looked. It was the first time I ever thought, “my body is perfect.” And the proportions were just, um, paintable. Like, sometimes people just are not so interesting to paint. Um, just the relationships of the sizes of things. And, um, just to have a weird, perfect orb in front of you that’s attached to you, it just made all the difference in terms of, um, a paintable shape. And I can’t really put into words what makes something paintable or not, but I guess it has to maybe do with a balance of volumes to flat things and having that one very, uh, clear volume, it allowed me to play with maybe flattening other areas or, I don’t know, oftentimes now I really think about, am I going to make a painting that’s mostly flat with a little bit of volume, or am I going to make a painting that’s mostly volumes with a little bit of flat? Like, I know when I’m sort of off, when there’s sort of an even amount of round things to flat things. And so I’ll add more stuff oftentimes to make it usually about more volumes. But it’s a strange thing to tell people like, oh, I’m thinking about flats and volumes when they’re looking at, like, a naked lady. But, you know, I feel like, yeah, no matter what, it’s going to be a naked lady who’s pregnant, but it won’t be a good painting of a naked lady unless I’m thinking about all the other stuff, which makes a painting function abstractly.

I feel like the stories emerge, these sort of subtle stories about just being a person in the world, when I’m focusing on the abstract elements like how much light to how much dark, how much flat to how much volume, um, what kind of colors, is it going to be mostly cool with accents of warm or warm, with accents of cool and, um, suggestive versus overly detailed, like all those decisions contribute to somehow the story. So I don’t think I’m going to make a story about, like, I just sat there, enjoying the view, (laughs) the way the light hit stuff started painting, and then suddenly this painting was basically about…everything. My entire life. Like I said, like, I’m very serious about painting. I want to fit it in. I love my children. I’m never smiling in the paintings, and the kids aren’t either, because most of the time we’re not smiling. Like, I really want these paintings to feel authentic. There are so many schlocky paintings, say, of babies, puppies, you know, um, families. You see so many family portraits on a Christmas card where everybody’s smiling, just like, no, I want to see what you really look like. And this probably came from my childhood. Where? There. My father was obsessed with getting a good photo of everybody every year. He had a lot of nice cameras he liked, but it was torture. He, he wanted everybody smiling, and there was always an argument, and someone was crying, and now I feel like… that would have been the greatest picture!

Somebody crying, somebody hitting, somebody’s laughing, somebody pulling down their pants or something, I don’t know. And so when I, um, you know, I’ve dabbled in that with my own family’s portraits. Um, by just, you know, holding up the video camera, sometimes I will sometimes start with a video that has, um, very low resolution just so I can get a pattern, pattern of dark and light. But, um…I so prefer an authentic scene of a family. There’s no reason to…to say something otherwise.

I saw this Alice Neel show with Smith, when I first started working there in the 90s, I think they had a show of her work and there was a pregnant portrait, naked pregnant woman. So authentic, so human, and I don’t think I’d really seen pregnant portraits before. It really blew my mind. And I thought, when I am pregnant, you better believe I’m going to do that.

I write music, I write songs, and I consider a lot of them to be musical portraits, and what I learned through doing painted portraits, I kind of want to come through, I want that– those qualities to come through in a song I write, and I did a lot of birthday songs, and so the mood was supposed to be kind of how much I love this person. And in my paintings, I really want the viewer to know how much I love painting and how much I love my babies. Um, and I had recording equipment, and so I would record the songs and do arrangements with lots of different instruments that I play and the act of balancing. This instrument. This distortion, or this reverb. It was so similar to the way I balanced colors and, and things like that in paintings. Um, and that overall emotion I wanted to get, I realized was really similar. So they are, they really go hand in hand; my love of writing music and just playing other people’s music too, um, and painting. I just feel like the arts are all so related and, um, you know, I really want to make work–both music and art– that communicates an emotion. Like, I want you to have a visceral–I want it to affect you viscerally. Like, songs can give you chills. I want my paintings to almost give you chills, if it’s possible. But to really be, you know, you know, to feel like a warmth looking at, um, a painting or to feel love versus cute. Like I have– one of my favorite paintings is my dog Rudy. And, um, I really did not want to paint like a puppy, a cute puppy. I want you to look at that and feel how much I loved that animal. Um. And same with my songs. I want you to cry when you hear them.

The science professors have, the students are doing their research, sorta–they’re participating in the research. Well, I’ll come up with something that I think is a really good idea, and I’ll have just the students do it. Like, some of the prompts, I’m like, “oh, that would be a really cool idea,” and then I just have them do it and I’m like, oh, I don’t have to do it now because they just did it. (Laughs) Um, but they’ll do things that are so inspiring to me. And, um, I guess I- (pause) I come up with so many ideas, it’s, it’s, there’s so much back and forth. It’s hard to say if my studio practice is always affecting the, um, what I do in the class or if the student work suddenly inspires something, but, um, I guess being an artist really, really does help me, um, just change up the classes too, and in interesting ways…they’re, they’re very important to one another.

I guess, I don’t want to have to scream to be heard. I prefer to whisper. Um, I like to make the most of the small space, I want it to feel enough. You’d look at it and you wouldn’t question “why is this small,” it would be just right. I’m interested in people. The way people relate, human psychology. I’ve been working on some other things that have some other issues, but I think it might be similar, like, they are facts. And right now I feel like wow, facts matter a lot. The truth, facts, nothing made up. And with my family paintings, I really want the truth too, like, there’s not a lot of laughing and smiling going on right now. Everybody’s in a bad mood, kind of. Or I’m serious right now, I want to paint, like, that seems–the love can be there, but with that serious quality that, you know, the world is, there’s a lot going on in the world. Even if you’re, you know, just home with kids, that’s, there’s so much going on. There’s such a range of emotions. Um…and there’s not one emotion, I think, in the paintings, they’re, I try to get the expressions to have almost every emotion, but no emotion. And so I change those faces a lot. There’s no, like, clear smirk or almost smile. It’s sort of, you can bring your own, um, give it, you know, bring your own take on what the expression is. It’s blank enough that you can project on to it.

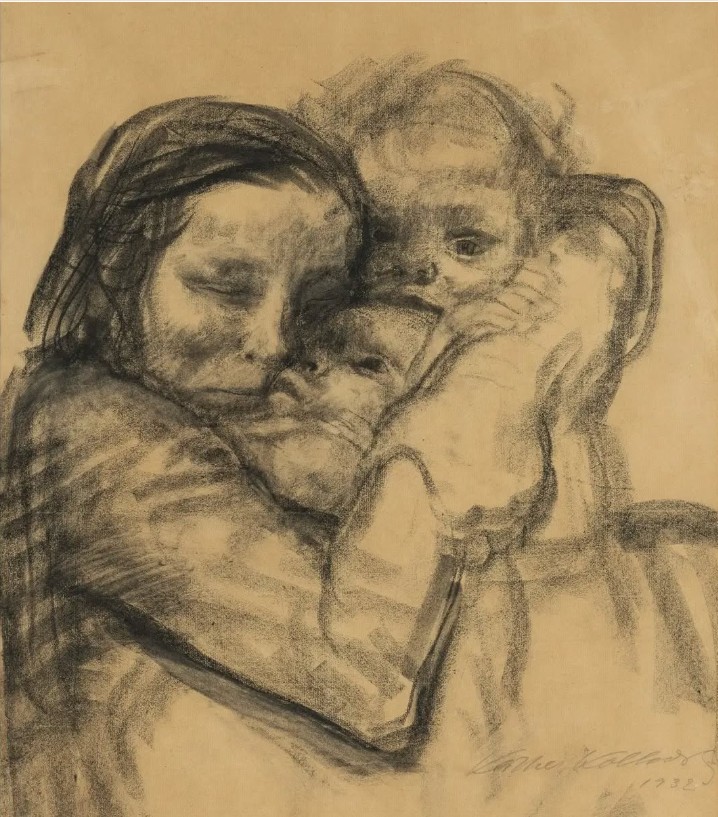

But I grew up with Kathe Kollwitz’s posters. My father loved Kathe Kollwitz. And she was a very depressed person and she was doing these lithos, she and her children, and she lost children in the war. Um…I didn’t know that when I was looking at them as a kid. But I was very taken with that sad element, and I guess, you know, my, my mother was kind of frazzled, my father was kind of frazzled, there were seven children, and my– my father, um…both my parents, uh, were from Jewish families who, you know, my father’s relatives were in the Holocaust. So there’s a sadness that carries down and…there was a sadness in the house, and so those felt extremely truthful to me and they really made a big impact on me, just like, how love and sadness are very intertwined. Like you can love something so much that it’s painful, and you can see that in her work because she did lose the children. Um, and, knowing about her depression, it’s right there, but the love is still right there. She’s, you know, mom and babies are really connected. Um, in a very unusual way. I guess I’d seen mostly sort of Madonnas and Jesus, you know what I mean? And that’s a very different depiction. But Kathe Kollwitz’s ones with her children, it’s wow, they’re heavy. So heavy.

And so I, I– that resonated with me, not just because I saw her’s, but I guess it was true to life. Life feels heavy to me. But at the same time, there’s a lot of things to lift you. And that’s why I paint. It’s easy to get bummed out and…painting is medicine. Painting makes my brain feel better. And so I kind of have to do it. Otherwise I go a little nutty.

Why do you make or look at art? What does it do for your brain?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Katie Schneider on Painting Techniques, Her Process, and Working Small

Transcript

One big theme is making the most of a small space, I would say. So all my work is small, it’s almost the size of your head and typically it can fit in my lap. Which is how I’ve always worked. Um, as a child, I worked that way. In graduate school, I painted sitting on the bed because there was a mirror, um, that I was working from, and um, I was tiny in the background of the mirror, but I was getting sort of all this stuff in the front and me relative to that stuff. So I’ve always just liked being able to hold the painting. And, um, I really have always enjoyed doing the figure. So I keep coming back to the figure I’ve– I’ve done a lot of still life too, but in both I’m really trying to figure out how to make a– how to make the most of a small space and how to make that, um, painting feel much larger than it would feel if it didn’t have anything on it. And that’s a case of manipulating the scale.

I find oil paint really forgiving. Like, I can make a lot of mistakes and just wipe them away. And that’s part of the reason I like to work small, too. Like there’s not a great investment in paint. So I could lay down really thick strokes and not care about the cost of it. Um, I love how paint, you know, the more you layer it, it turns, it just changes. Um, There’s something just very creamy and delicious about it. And I did start learning how to paint using acrylics, and I enjoy those sometimes. But oil painting? I don’t know, you can just get effects, um, that are not possible with other types of paint, and I can get super detailed now with oil paint. The ones that are in the museum are not particularly detailed, um, because they’re on canvas, but now I’m working on metal and I can get incredible detail because the paint kind of glides across the surface. These are much more suggestive, like they’re kind of blotches of paint. And I really like how the viewer gets up close and they can see that’s just a bunch of strokes. But then you step back and it feels like a real space with a real sense of light. Um, and…it’s kind of magic.

You know, bigger is not better, always. And I’m a crazy recycler, so I do not like to throw things away. And that those paintings actually have probably several paintings underneath them that didn’t quite work. So that’s, I guess, one thing I think people might not know looking at them, that there were a lot of duds underneath, and that I have to paint many paintings in order for there to be one good one. And, uh, you know, you just have to stick with it and slog through until something decent emerges. So that’s one thing I think people wouldn’t know. Um, I’m not sure people would realize that they were done literally right from the mirror. I did not use photographs. And right now everybody seems to be working from photographs. I don’t get enough from a photograph. And these, I would just set up a mirror in my kitchen. Those two are from my kitchen, and just return to the spot each, um, each evening. I think the kids were often in bed, but the one with, um, my daughter, who, uh, appears in the painting ninth month, I–it was originally just going to be a portrait of me, and then she sort of just toddled in, and she liked to just sort of stand by me sucking her thumb, and I literally got her in two minutes. I just thought, oh, she’s right there. That looks kind of good, I’ll just try it, and you can see the strokes are really loose and there’s hardly any of them. But I know that head very well. And I’ve painted her, drawn her a lot. So I literally got her in two minutes and it made the painting and that was extremely exciting. I don’t plan a painting. I don’t draw it first. I don’t know if people would realize, you know, there’s just sort of like, I, I’m drawing when I’m painting.

Another thing about the ninth month one, the ninth month one was that I’m only using four colors, and for several years, like five years, I only used black, white, ocher and burnt Sienna as a way to figure out um…really how to get an interesting, um, glow, how to get a deeper space and color was kind of getting in the way and disrupting just a kind of, uh, unity that I really wanted to get. So I don’t think– I hope when people look at that painting, they’re not thinking, “boy, that’s a limited palette” (laughs). I want those four to have stretched and for people to just not even think about, uh, think about the colors, but really get interested in the light. The other thing people might not know is that I had a chair next to me with a standing lamp that’s not included in the painting. I always have my easel because I really, um, want it clear that the audience knows that I’m a painter. I’m very serious about painting. I’m very serious about being a mother. And, um, I’m trying to get my entire world in one frame. The light though, the lamp is my most important tool, though. Beyond, uh, even the paints themselves. Like, I need to set up the light to capture these sorts of lights and shadows. And that’s how I make the little paintings seem big.

And also that’s how I can make things fast. I really like to paint quickly. I just don’t have patience, and so I might make many paintings, but they’re all done somewhat quickly. Um, they’re hit or miss. But that one, the ninth month, probably took 2 or 3 sessions (pause). Oftentimes the quicker ones are the best ones. They just, I’m sort of just… channeling something? I don’t know, or I just worked many–many days and then suddenly had a lucky day (laughs). You never know what’s going to work, really, and for some reason, that one just worked, and it happened quickly. Although they say, you know, it takes a lifetime to make each painting. It’s however much time you’ve put in up to that point. Yeah. The other one that has, um, two children and a basketball family portrait that took a lot longer, that’s a much more complex painting. And, um…it was–it was super hard to get the space, um, clear, and the composition to feel just not so chaotic, and my goal really is to organize chaos. I want a lot of stuff in there, and there’s very few paintings of mine that are sort of simple. I do not know how to do that. I can only take too much stuff and then kind of juggle it, and that works for me.

What part of this process was most unexpected? What about these paintings makes them work in your mind?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Barry Moser on His Career

Transcript

Eva: Can you talk a little bit about why you chose illustrations?

Moser: It chose me. I didn’t… I majored in painting in college. Um, looked down my nose at illustration. You know, as all good art students are supposed to. Uh, then I found, I moved to Northampton, uh, and it was just an entirely different world than what I was used to. Met Leonard Baskin. I saw fine books. Really fine books, for the first time in my life. A fine book is not the same thing as an ordinary book. I mean, you have such a huge difference in materials, craftsmanship. So, um, I saw these fine books, and I just, it was right for me. So I got into illustrating fine books. Um, and then in 1985, I was invited to illustrate a children’s book, which I was not excited about doing. Because, again, as all good serious artists know, that’s not real art. Which is, of course, bullshit. Pure-D, first class bullshit. Um, so that’s how I got into it. And I found that I was pretty good at it, and I enjoyed it, and I’m one of those people who never goes to work.

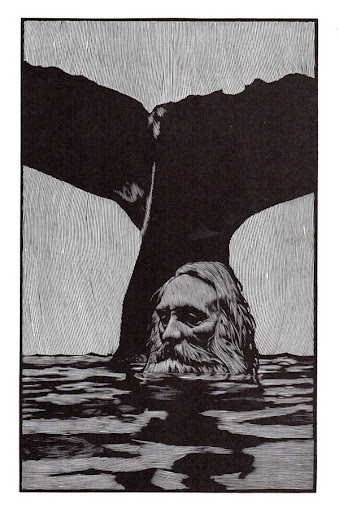

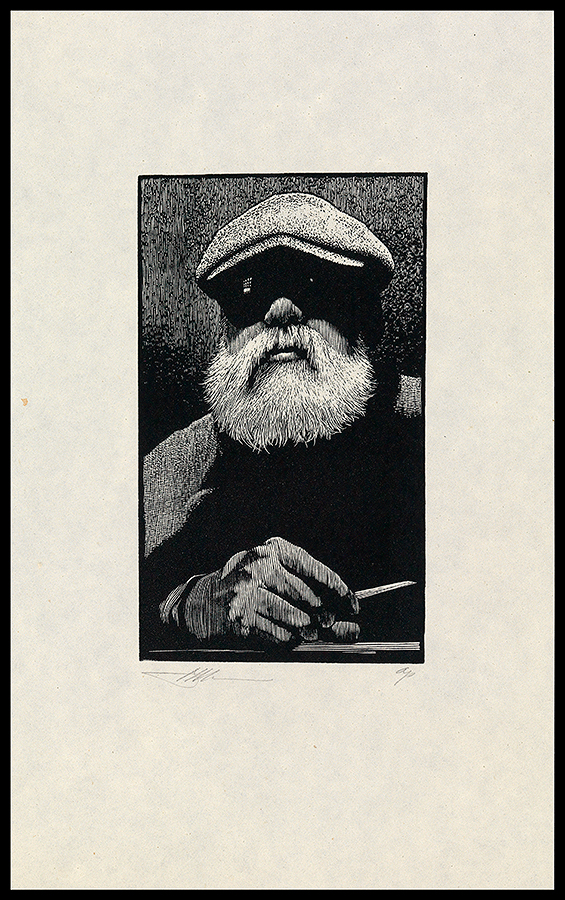

Wood engraving, I came by another route. When I was in college, my first year in college, 1958-59, and I was at Auburn University in Alabama, and I was an art major, first year. As you know, you know, you’re required subjects in the first year. As I was the first year there and I was in the library, I was reading a, uh, magazine, Art in America or something like that, turned the page, and there was this image, a circle, a tornado, as we call it. It was an engraving by Leonard Baskin. I’d never heard of Leonard Baskin. But it just fascinated me. I was, I was taken away in a way that I’m seldom moved by, um, especially contemporary art. I’m moved that way by Franz Kline. And I just vowed that day, yeah, sitting there on a rainy afternoon in a library that I was gonna learn how to do that. And I did. And now I’ve done…(laughs)…a few thousand. I stay busy.

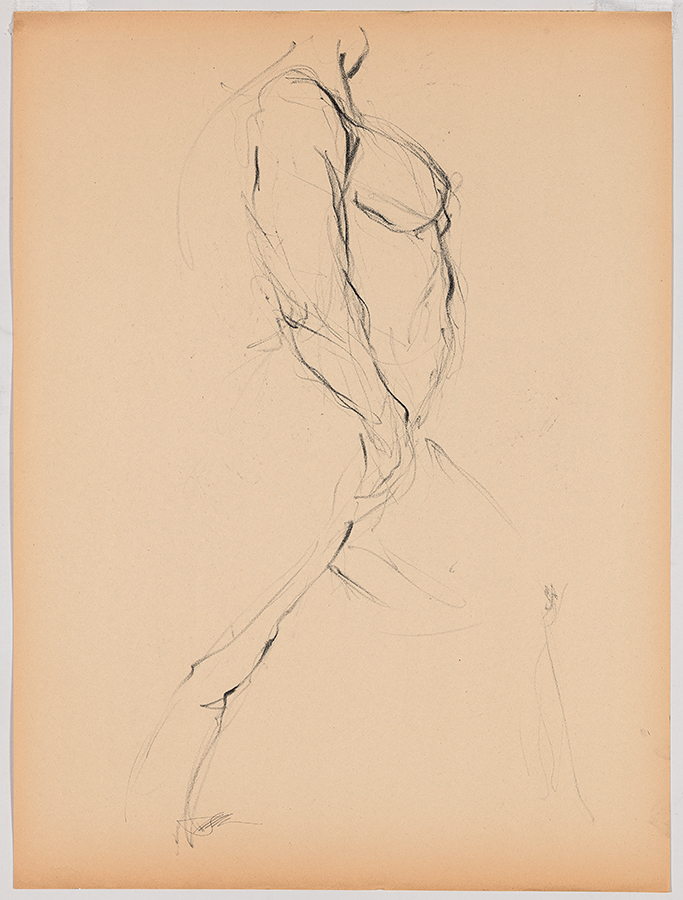

One of my favorite mediums is number two pencil. I mean, I love my pencils. I also do some experiments, too. I was originally very much a luddite. I am still, if you talk to my students in there, they will tell you even now, “that old man is a luddite,” but I’m not–I don’t fear the technology, it’s just I’m very good at it. But I did learn InDesign and Photoshop. And in Photoshop I don’t use color, I don’t know anything about color in Photoshop. But when I discovered that medium, it took me to a different place. It took me to a way of, of creating images that I had not done before. So I’ve been experimenting with, um, combining my preliminary work with–with drawing. It’s the way I’ve done the last couple of books. Well, the last book that I did that was not illustrated with engravings was done that way; by developing a composition, printing it out on a piece of good archival paper, but very shady, very much a ghost on the paper, and then drawing over that. Um, I mean, I find it fascinating. It’s– it has taken its toll, however, on my drawing skills. So if you look at those figure drawings that, uh, we have in the collection up there, they’re pretty loose, and pretty nice, I can’t do that anymore. And the reason, I mean, I could get back to it, but it would take a lot of work.

Eva: Can you explain, uh, the process of wood engraving and what it entails?

Moser: I wrote a book about it. Two major differences: wood. A tree grows this way (holds arm on table and gestures vertically). This is a plank grain. If you cut plank out, if you go across it this way, it’s end grain. Wood engraving is done on the end grain, woodcut is down on the plank. Woodcut is done with open gouges and v gouges, parting tools, whereas engraving is done with a solid shaft of steel. There’s no–no cup to it. Wood engraving is–is a broad medium ….woodcut is a broad medium, wood engraving is a fine medium. Um, now, beyond that, I’m pretty sure they have a copy of my book in the library over there, (laughs) see, if you want to know more.

Eva: Yeah, that’s, that’s perfect.

Moser: Yeah. Okay.

Eva: Um, so, like I mentioned, you have 250 things in the–more than that, in the collection. Is there any subject matter in particular that you come back to especially often?

Moser: The human figure and even more specific in that, um, the, uh, the portrait. The headshot.

Eva: What is it about that that interests you?

Moser: I just–what we’re doing right now? We’re looking at each other. Yeah, your eyes are on my eyes, my eyes are on yours. You’re smiling, I’m smiling. I just love to watch faces. Um, and I, when I was your age, uh, when I was in college, I was scared to death of doing a portrait. And then we had to do a self-portrait, and I thought “oh, my God,” it was even worse. And then I did a few self-portraits. Today, I probably have 6 or 700 self-portraits that I’ve done, over the years, because I started when I was in my late 20s. And they just keep coming. I can do them, I mean, I’ve done demonstrations, you know, with a group of students out there and do a self-portrait just off the cuff, because I’ve done so many, I know how to do it really quickly.

Eva: In the collection, is there anything that, that you especially like?

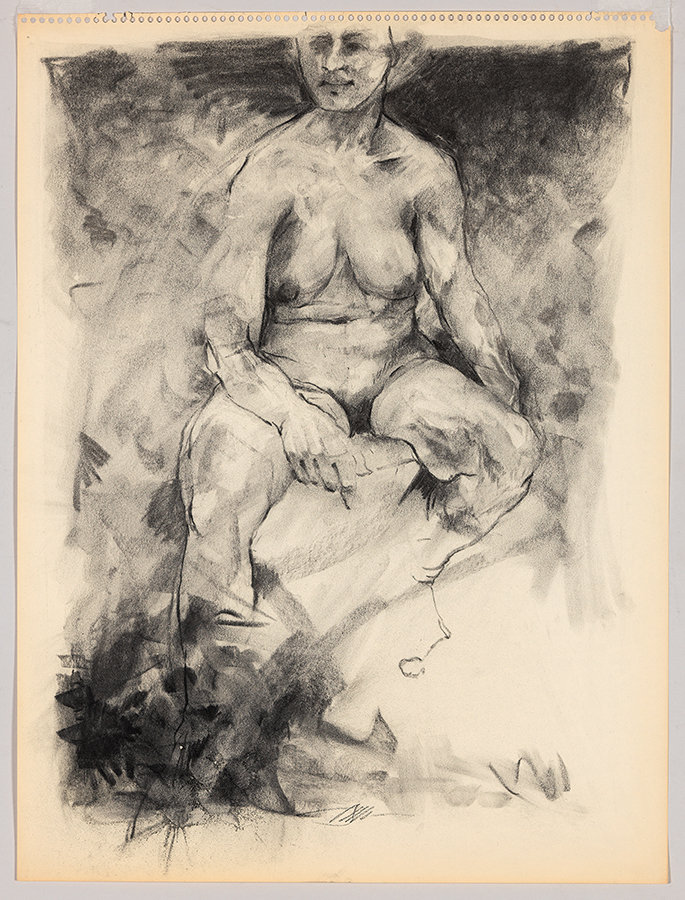

Moser: Those figure drawings. And the reason for that is because I forgot all about them, because those drawings were done when I went to UMass for graduate school, because I didn’t have an MFA when I came up here. And for the record, I still don’t. I did them in a class when I was 30 years old, and everybody else in the class was in their 20s, and I was here, already out in the world selling some prints and stuff and teaching at school, teaching art, teaching the very thing I was there to do. And these kids over here? They’re doing it better than I’m doing it. The reason for all of that, and the reason that those drawings mean something to me, is one, I was upstaged by younger students, which called me to do better work. And then some of those drawings happened to be of my…wife. Uh, she was my wife then. Yeah. I don’t think she’d want anybody to know that necessarily (laughs). Yeah. So they’re–those drawings signal a real shift in my career, and I, because when I was in college, Jesus, the first couple of years, I didn’t make my grades. When I graduated, I think my grade point average was probably 2.9, 2.8, something like that. Because my first years were so bad and, um, I failed algebra, college algebra, I failed American History, twice, um, and so on. I mean, it was– and when I went to apply to graduate school for the MFA, I got turned down. Every place I applied turned me down without looking at my portfolio…until I got here and Lennie Baskin wrote a recommendation of me at UMass. UMass accepted me, I got into the program, I did one year. I was teaching a school, Williston Academy, down in East Hampton, a full teaching load, plus doing theater. And I was doing this, my graduate work on my own time at night, and I did that for a year. I pulled out a four point average, and I quit. Someone told me one time that MFA is teaching–is your union card for teaching in college, and I just never quite accepted that. That’s why I don’t have one.

Post your reaction to this interview. How could wood engravings like these transform a fine book?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.