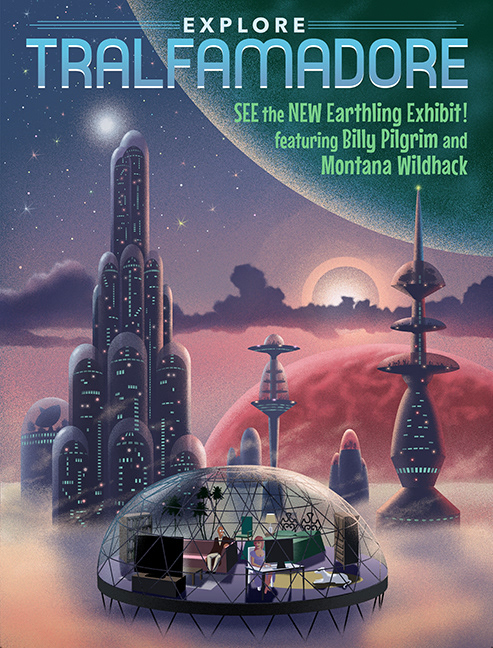

Kurt Vonnegut’s fictitious alien species, the Tralfamadorians, have an intriguing way of thinking about and existing in relation to time. As Vonnegut writes in Slaughterhouse-Five, they can “look at the different moments just the way we can look at a stretch of the Rocky Mountains, for instance. They can see how permanent all the moments are, and they can look at any moment that interests them,” and not merely look, but inhabit. For them, the you of 20 years from now, the you of 5 years ago, the dead you – they’re all the exact same self. This way of being frees them from a lot of the suffering humans experience (you can’t really mourn a past or dread a future when all time is permanent).

We humans are used to thinking of moving from one moment to the next in linear order, carrying our experiences along with us; so it’s quite hard to imagine what this nonlinear way of existing in time would even feel like. But Vonnegut gives it a shot. Billy Pilgrim, Slaughterhouse-Five’s main character, becomes untethered in time sort of like the Tralfamadorians are, moving between his wedding and his life as a widow within moments. He’s never sure what part of his life he’ll act out next.

But is Billy really free from time? Philosopher David Velleman suggests no. Billy, as it stands, still moves through time in a meta-order, popping from one place to another, always the same self through it all. He still has this enduring self, the Billy that is present at every moment. Velleman will suggest that this idea of an enduring self is something many of us mistakenly endorse. It comes from the structure of our memory. For example, when we recall the cake on our own fifth birthday, we recall it from the standpoint of the five-year-old. Then we make a mistake, we think of the toddler who smashed their face into the cake as the same self who is remembering that moment. Thus, a single self appears to be present, in continuity from one time to another. But there’s something confounding about this way of thinking of the self – how could I be the same self at 89 and 22? I surely have had new experiences in the interim? And likewise, it seems intuitive that the Billy who gets married isn’t the same Billy who is a widow.

Velleman considers an alternate suggestion: that we might perdure rather than endure. If an object were to perdure it would extend through time like it does through space. We know that a single point in space can only be occupied by a part of an extended object. To perdure, then, is to have temporal parts that come one after the other, each part confined to a moment in time. Under this view five-year-old you is different than the current you, in fact, each “you” is confined to the moment it exists in. The self in this view is a process, you might imagine performing a rendition of your favorite theme song. Each note that is played is a temporal part. The notes are played one after the other, the first note, the second note, the third… they exist in that moment and not in the next – but all are part of the song.

Velleman pushes the idea of perduring further than many other scholars of analytical philosophy. He says that when we think of ourselves as perduring we disconnect from the passage of time. If you have ever “lost yourself” or “lost track of time” when you were busy experiencing the present moment, wrapped up in a good episode of Star Trek for instance, this might ring true to you. In those moments we seem to be drawn out the passage of time and experience the ‘self’ as confined to a now. When we’re bored, like I often am in a long lecture, the same story doesn’t hold true. I start to think about my “self” again, becoming aware of what I’m going to do after class, and what I did before class, and what I wish I were doing instead of being there, and I am painfully aware of the clock in class ticking.

Buddhist’s suggest that the solution to avoiding the suffering that pervades all of human existence is to accept that the enduring self is illusory (and if we believe Velleman, that the passage of time is illusory too). This would free us from the mild boredom we experience in class, sure, but more importantly, it can help us tackle more serious things like fear of death or pain. It would allow us to stop worrying about all the things that have ever happened and all the things that will happen, instead focusing on the things in front of us in the moment. If we succeeded in this mission we could respond to life as the Tralfamadorians do, and greet these big scary things, like death, with a simple “So it Goes.”