The American narrative is as familiar to me as it is to anyone living in the United States, present from the picture books I read to elementary school history lessons. The story goes that America was founded by revolutionaries, who, tired of living under the British monarchy, bravely declared their independence and created a new government that would represent their interests and respect their rights. This new form of government empowered them to create a society where each person could succeed on their own terms and live a good life. And their ‘great experiment’ was also a great example: of the power of people united to advocate for themselves collectively, and of the equal dignity of all individuals, proving each person worthy of controlling their own destiny.

As familiar as that story is, we all know the facts equally well: that the American ‘revolutionaries’ were a group of wealthy, white, men; that they were focused on their own financial destinies, and primarily tired of paying British taxes; that their new government only guaranteed the rights and dignity of other land-owning white men; that they violently abused the dignity of other individuals by enslaving them, treating kidnapped African people as less than human so they could get rich off of their labor.

In her book This America, historian Jill Lepore argues that this kind of hypocrisy and contradiction emerges from the struggle to create a nation from very disparate groups of people, and characterizes all of American history. Lepore explores how Americans have used nationalism to make different stories from America’s contradictory history, sometimes reiterating racism and hypocrisy, and sometimes striving to reach past it. Drawing on the history of American nationalism, she attempts to move towards a positive, unifying vision of the nation, supported by an honest and comprehensive shared past.

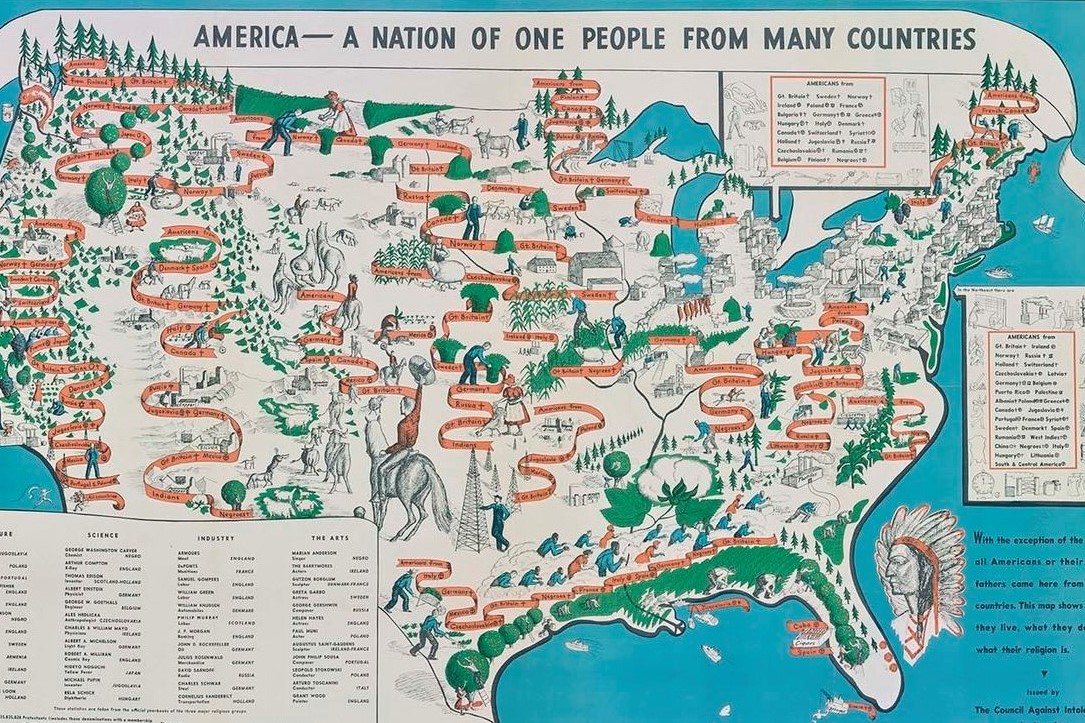

Part of the struggle of forming a nation without a shared ethnic history is deciding who belongs, who gets the rights of a citizen, who counts as American. To Lepore, the nation is that struggle. The challenge for historians, then, is to decide who counts as American in the histories they tell, especially when some people in American history have done atrocious wrongs, and some people in American history haven’t actually wanted to be called American. The history Lepore tells includes a wide range of articulations of who belongs in the American nation. There are broad calls for inclusion, reflecting the “give me your tired, your poor” rhetoric of the Statue of Liberty, and more pointed ones, like Mary Church Terrell’s call for equal rights for Black Americans. There are endless examples of racist exclusion from the nation, from immigration quotas to legal segregation to violence and terrorism. And there are groups of people who gave up on the American nation altogether. Some of them did so for racist nationalist reasons, like the Confederacy in the Civil War. However Black nationalist groups, and many Indigenous people, like Chitto Harjo, from the Muscogee Creek Nation, and Queen Lili‘uokalani of Hawaii, made strong cases for their right to self-determination and independence from the United States.

Lepore is clear in her description of the harm and violence racist and falsified national stories have created throughout American history, through misrepresenting acts of racism and through leaving out stories that challenge the idea that American ideals have already been realized. But she also criticizes modern liberals and globalists for retreating from telling national stories at all. A fake national past is harmful, but to pretend we have no national past is just as fake—as she says, “it’s no use pretending people don’t live in nations.” Neither racist nationalists nor globalist intellectuals are connecting to the reality of American history, with both its violence and evil, and its real acts of resistance, courage, and radical progress. Instead, Lepore wants us to use national history to face the nation as it is.

How can we go about that? The history in This America is a good starting point. But Lepore’s specific calls to action feel weak and potentially misdirected. Lepore admonishes historians not just for retreating from telling national history, but for failing to tell a patriotic story to unite Americans against racist nationalism. She praises Carl N. Degler as “quietly heroic” for warning the members of the American Historical Association that if they didn’t write histories of the nation, divisive nationalist narratives would take over the space left in the public opinion. But of course, public opinion is set in many other more pervasive ways than scholarship—in songs, cartoons, and picture books like the ones I read as a kid. Turning to politicians, she condemns liberals for not opposing Donald Trump’s nationalism with a message of courage and hope. But her push for patriotism and unity seems at odds with her emphasis on reckoning with history, and reality, as they are.

At its broadest and most basic, This America is meant to be “a case for the nation.” Yet the evidence and the argument don’t hold together. In the concluding chapter, she restates the American myth of that she’s spent the rest of the book refuting through facts: “The United States is a nation founded on a revolutionary, generous, and deeply moral commitment to human equality and dignity.” From the stories she has just told us, we know that has never been completely true. If she’s offering it as a motivating, unifying story, an idea of nation to save the reality, the gesture feels weak compared to Chitto Harjo’s assertion that America was founded “for the white man,” and Mary Church Terrell’s unmet demand for full citizenship for Black Americans. The greatest advocates for democracy and equality, in Lepore’s own eyes, were thinkers like Frederick Douglass and W. E. B. DuBois, who she herself describes as long ignored, “challenges to be met.” Patriotism and unity aren’t enough to meet their challenge. But by telling their stories, This America may bring us closer to creating the nation they envisioned.