Pairing musical analysis with feminist theory, Aiden Hahn examines the ways in which Björk’s Vespertine subverts traditional feminist messages. Hahn investigates the concept of the domestic within Björk’s world, detailing how a space traditionally limiting for women was liberating for the artist. Ultimately, Hahn identifies how Björk has consciously reclaimed the domestic as a part of her identity, disabling the patriarchy from using it against her. –Lilia Wong ‘25

A Patchwork of Femininity: How Vespertine Empowers Women Within Domesticity

Aiden Hahn ’27

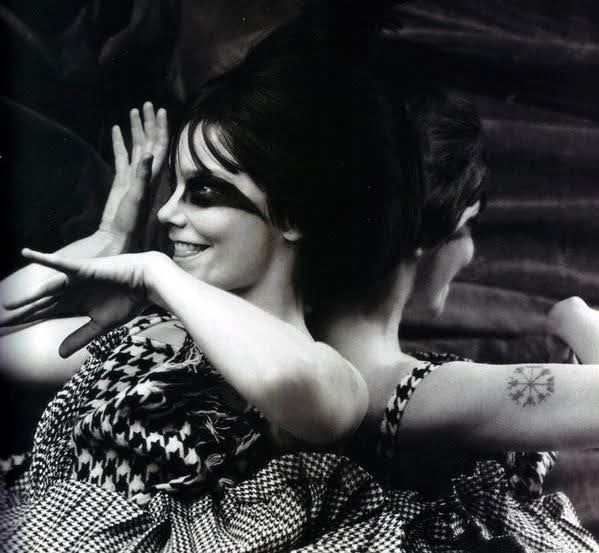

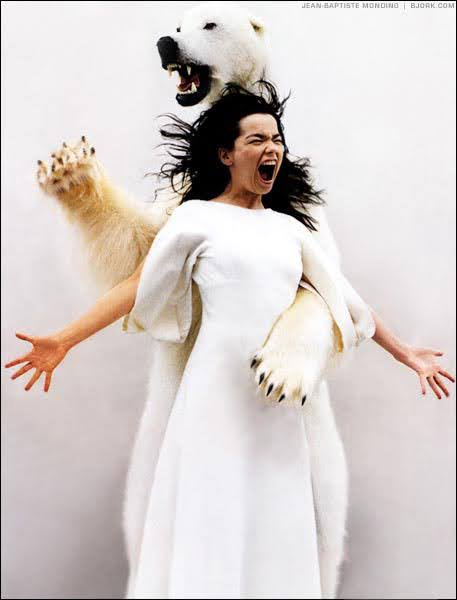

“There lies my passion hidden/ there lies my love/ I’ll hide it under a blanket/ lull it to sleep/ I’ll keep it in a hidden place” (Björk, 2001). Björk is a singer and songwriter who has carved out a niche within pop music with her quirky, eclectic style that infused her Icelandic cultural heritage with 90s electronic and punk-rock influences. Her lyrics are brazenly feminist, and in most of her early songs, Björk screams anthems of female rage and lust over catchy yet aggressive instrumentals. Her first three studio albums to feature this distinctive style were each commercial successes, launching Björk into a six-year nonstop world tour through the mid-90s. By the end of the tour, Björk found herself “physically exhausted,” and her home became a source of reliable, consistent peace and artistic inspiration (Eir). For her fourth studio album, Vespertine (2001), she took an intentionally sharp stylistic turn towards soft and subtle sensuality, “meant like a new way to make a home” (Eir). Vespertine blends the male-dominated medium of electronic music with traditionally light feminine vocals and instruments, as well as sounds from the artist’s home, implying that domesticity does not have to be a powerless void restraining women, for women can embrace the conventions of domestic life to construct empowering identities and discourses.

The blending of everyday domestic sounds into the electronic production of Vespertine challenges the early feminist belief that women have been robbed of authority and power due to a societal banishment to the home. In Gendered Spaces, Daphne Spain writes of the phenomenon of the domestic sphere and male-dominated industries having been intentionally kept apart. She observes that “throughout history and across cultures . . . women and men are spatially segregated in ways that reduce women’s access to knowledge and thereby reinforce women’s lower status relative to men’s” (Spain 3). In the article, “Not Subordinate: Empowering Women in the Marriage-Plot,” literary critic Julie Shaffer provides a reason as to why this separation of the workforce and the home has become so pronounced. She claims that the droves of men drawn to urban factory jobs during the Industrial Revolution “contributed to the home’s becoming increasingly viewed as a haven from society . . . it became increasingly difficult to see women’s realm of action as reaching from that distant hearth into society at large” (Shaffer 68). Björk, however, updates this old model of systemic sexism by fueling her artistic endeavors with the pride she feels in her domestic lifestyle.

Vespertine takes place within the home. The album, which was initially titled Domestika, comes to life with the sounds of Björk’s home environment: snow crunching under boots, ice cracking, cards shuffling, and a hand tapping on a dining table. Björk recorded and produced the entire album from her home computer, editing the domestic sounds into patterned rhythms and surrounding them with electronic synth performances and ethereal vocals on a music production software (Eir). And while Spain may have seen this as another unfortunate example of a woman trapped in a domestic realm created to keep her away from society’s power, the creation process of Vespertine proves otherwise. In an interview about Vespertine, Björk remarks that

“It was like paradise: domestic life. I would first have to create . . . a new way to make a home including my laptop, and including my newfound self-sufficiency, being able to work at home . . . having the whole album in my laptop gave me freedom, and also liberated me as an author and as a producer to weave together all the songs . . . the craft of that is quite feminine.” (Eir)

With her personal computer, Björk was able to creatively control her own songs from within a construct that has traditionally represented women’s lack of agency. She transformed the male-dominated field of music production into an at-home craft like those associated with women. This crossing of the gendered domain/work boundary insinuates that domesticity is not distinctly separate from the industry. Björk found in the domestic sphere a freedom to explore a practice that has been historically reserved for men, and instead of venturing “into the patriarchy system” (Björk) of an industry music production studio, Björk created her own art in her own home on her own terms, which is an entirely empowering action. On top of that, the inclusion of domestic sounds in Vespertine reminds listeners that domesticity is a fluid dimension, thereby encouraging women to explore anything traditionally entrusted to men—whether from within the domestic sphere or an industry.

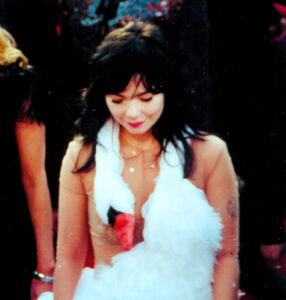

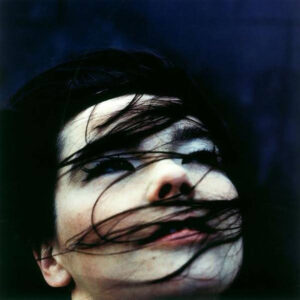

Vespertine is a patchwork of female iconography. Björk’s soft, traditionally feminine vocals and her collaborations with a female harpist and an all-women choir throughout Vespertine reveal that women can find power in embodying and embracing the stereotypes created to control them. Sonically, Björk composed the album with instruments like the glockenspiel, the clavichord, and the celesta which produce thin, light, angelic sounds—sounds that have been traditionally associated with delicate femininity (Eir). On nearly every song on Vespertine, Björk is accompanied by The Greenland Choir, an all-female Inuit choral group, and Zeena Parkins, a female harpist who combines the instrument with electronic modifications. Aesthetically, Björk’s vocals throughout the album are overwhelmingly gentle and hushed, with songs like “Cocoon” and “Undo” performed barely above a whisper. Women have been traditionally portrayed as dainty and quiet, so compared to Björk’s earlier albums in which she yells alongside fiery jazz compositions, Vespertine’s quiet voice and feminine instruments clearly present an intentional embodying of female stereotypes.

But why would a female musician attempting to empower other women lean into stereotypes that have historically been used to subjugate women? Music critics and journalists Simon Reynolds and Joy Press address this in their book, The Sex Revolts: Gender, Rebellion and Rock ‘N’ Roll. They argue that in order to cultivate respect and authority, female musicians celebrate female imagery and iconography . . . [some female musicians] shift between a series of female archetypes in a strategy of investment and divestment: using clichés without being reduced to them . . . women turn stereotypes against the society that created them. (Press 233-234) Stereotypes are developed so that certain demographics are generalized in the eyes of the public, effectively robbing people in those populations of individuality and autonomy. This is how groups of people are dehumanized and discriminated against. However, when people–in this case, women–consciously infuse their identities with their stereotypical conventions, a contradiction forms that breaks the system: how can a woman be stripped of her identity through stereotypes if her identity is informed by the power she feels when embracing those stereotypes? In other words, relishing in the ownership of stereotypes can be an empowering act that robs conventions of their subjugating power. Reynolds and Press argue that the practice of female musicians embodying historically feminine traditions “becomes a way of provoking and confounding the male gaze . . . these artists refuse to be tied down to any one identity” (289). Therefore, Björk’s proud masquerade of femininity in Vespertine challenges the idea that female stereotypes are a stifling sentence to life in the shadows of men, for she proves that an empowering dissection of patriarchal thought systems can come from an intertwining of domestic, feminine conventions and personal identity.

Through Vespertine’s lyrics, Björk confesses the empowering love she has found in her domestic relationship, while simultaneously acknowledging the dark underbelly of domesticity, proving that nuanced female-led discourses can emerge from the domestic sphere. In the eighth song on Vespertine, “An Echo a Stain,” Björk laments over an increasingly disturbing, pulsating beat, “one of these days, soon, very soon, love you ‘til then/ Don’t say no to me/ You can’t say no to me/ I won’t see you denied/ I’m sorry you saw that/ I’m sorry he did it.” (Björk, 2001). These lyrics were interpolated from the play Crave, written by Sarah Kane, which takes a grim, experimental look at domestic abuse, specifically that of her father toward her mother (Pytlik 172). “An Echo a Stain” appears to be out of place in Vespertine. The entire album up until this song details the infatuation, sensuality and comfort that Björk experiences because of her partner, and suddenly–over halfway through the album–a darkness bubbles to the surface. Björk interrupts her own outpouring of love with these stark words in order to bring sharp awareness to the ability of any relationship to stumble into violence and volatile emotions.

But just as abruptly as it emerges, the unease in Vespertine dissipates, and the songs succeeding “An Echo a Stain” return to peaceful passion. The final song of the album, “Unison,” presents one of the most vulnerable accounts of how Björk’s embracing of domestic life has changed her for the better. She admits, “born stubborn, me, will always be . . . have grown my own private branch of this tree. You, gardener . . . domestically, I can obey all of your rules and still be.” Domestic life has not made Björk sacrifice her identity, instead, it has introduced a new aspect to it–one that empowers her and encourages her individuality. Björk’s pairing of songs like “Unison”–which represents all the warmth and strength of her relationship–with “An Echo a Stain” reveals the duality of domesticity. The “branch” and the “tree” can be ruled by the “gardener,” or they can both thrive together and sustain each other. It all comes down to control of power in a relationship and if it’s entrusted to both partners equally. Björk wants her listeners to recognize this dynamic; to discuss it; to confront it.

In her article “Not Subordinate: Empowering Women in the Marriage-Plot,” Julie Shaffer argues that one should view the genre [of marriage and domesticity] as a site for some women novelists to participate in constructing and disseminating an ideology that granted women greater autonomy and respectability than that which viewed them as subordinate and inferior creatures (Shaffer 52). An unavoidable reality of patriarchal society is that women are not granted the same inherent respect and authority that men are born into. As Daphne Spain documented, women have been systematically designated to the home, so, society has historically dictated that women should only possess domestic, mother/wife knowledge (Spain). However, women have and will continue to exploit this niche source of intrinsic respect to speak and be heard. Since women are given authority in conversations about domesticity, they will write stories and craft albums about domestic life while subtextually engaging in deeper arguments, which will more likely garner widespread recognition and respect in patriarchal cultures (Shaffer).

In Björk’s case, the troubling side of domesticity brought up in “An Echo A Stain” is intentionally shrouded with songs detailing domestic feminine joy, so that a wider audience will actually listen and take this discussion seriously. To Shaffer’s point, women have initiated topical discourses through the medium of domestic art so that the men who are most at risk of perpetuating cycles of power imbalance are more inclined not only to listen and learn but also treat the conversation and the women behind it with respect. Vespertine references the issue of domestic violence which haunts relationships and home environments across generations. Conversations initiated by empowered female voices like Björk’s could hopefully lead to men recognizing the patterns which can lead to the cycle being broken. Therefore, female artists can effectively use the setting of the domestic realm as a tool to discuss and address systemic issues in patriarchal society.

Daphne Spain echoed the ideas of early waves of feminism when she argued that the stratification of men to the workforce and women to the home has prevented women from accessing the same social power as men, forcing women into a lower social status. While institutionalized sexism is a brutal reality that many women recognize and confront throughout their lives, this argument suggests that the domestic sphere and the industrial sphere exist in a concrete binary division with all of the power in society held in the latter sector; however, Vespertine demonstrates that this is not the case. Björk is just one of the many female musicians who steep their artistic personas in femininity and domesticity to prove that domestic life is not an isolated prison but a fluid space for personal peace and creativity as well as exploration into male-dominated industries. Women can advocate for themselves in culturally significant discourses and build unique identities that actively dismantle patriarchal constrictions–all from within the blurred borders of the domestic sphere.

If society continues to treat domesticity as an isolation chamber limiting women from the power men can achieve, crucial conversations and discourses on systematic patriarchal issues will not be properly confronted. For it is female artists like Björk who, from within the walls of their homes, take matters into their own hands, telling stories that empower them personally, and formulating identities that challenge both patriarchal systems and dated feminist perspectives. They craft albums like Vespertine that employ femininity in such an identity-enmeshing way that it robs patriarchal domesticity of its power to generalize and dehumanize women. When the domestic sphere is then recognized as a space for female strength and authority, more women will realize that they have the power to share their voices and their art on their own terms.

Works Cited

Eir, Oddný, and Björk Guðmundsdóttir. This is Sonic Symbolism, Episode Four, Vespertine. September 2022. Bjork.fr, Sonic Symbolism. Podcast.

Press, Joy, and Simon Reynolds. The Sex Revolts: Gender, Rebellion, and Rock ‘n’ Roll. Harvard University Press, 1995.

Pytlik, Mark. Björk: Wow and Flutter. ECW Press, 2003. Google Books.

Shaffer, Julie. “Not Subordinate: Empowering Women in the Marriage-Plot— The Novels of Frances Burney, Maria Edgeworth, and Jane Austen.” Criticism, vol. 34, no. no. 1, 1992, pp. 51-73. JSTOR.

Spain, Daphne. Gendered Spaces. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992.

Recent Comments