Norma Jean Haynes’ close reading of Jamaica Kincaid’s Lucy offers an insightful perspective on the author’s use of plants and gardens in the novel. Haynes highlights the ways in which plants and agriculture are a site of colonialism and slavery, while simultaneously noting their liberatory power. Beyond presenting a precise reading of Kincaid’s writing, Haynes also applies a keen and unique historical analysis to the novel, and reveals a deeper meaning in the natural world which surrounds us. –Ari Jewell ’22, Editorial Assistant

The Act of Possessing: Plants and Colonialism in Jamaica Kincaid’s Lucy

Norma Jean Haynes, Ada Comstock scholar, ’23

For Jamaica Kincaid, the garden is a place where history and memory grow into the present. Alongside her acclaimed fiction, Kincaid is known for her gardening columns in The New Yorker, wherein she has explored the colonial histories that often echo in plants and their cultivation. “The Disturbances of the Garden” is one such article, in which Kincaid draws connections between horticulture and colonialism, providing insight into the role of plants in her novel, Lucy. Kincaid describes gardening as an “act of possessing” that constitutes a luxury extended to those in positions of power along with the privilege of experiencing plants as beautiful, rather than strictly useful (“Disturbances” 5). Through plants, Kincaid expresses the enduring consequences of colonialism, including exoticization, generational trauma, and social inequality. Through the character of Lucy, however, Kincaid proposes a postcolonial relationship with plants—a “repossession” of the garden centered on individual growth.

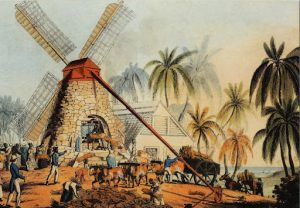

In “The Disturbances of the Garden,” Kincaid references Eden as the original garden, naming agriculture as the Tree of Life and horticulture as the Tree of Knowledge. “We cultivate food,” she writes, “and when there is a surplus of it, producing wealth, we cultivate the spaces of contemplation, a garden of plants not necessary for physical survival” (4). Kincaid writes here of horticulture as a luxury, reserved for those who have the resources to concern themselves with more than the survival of the body. This way of thinking belongs to Kincaid’s output as a postcolonial writer, acknowledging the historical connection between commercial agriculture, colonization and enslavement. The American agricultural system has relied at various points on enslaved, indentured, and undocumented immigrant labor; the same is true of Antigua, where Kincaid was born. Meanwhile, the majority of wealth, and of contemplative space, continues to reside with the descendants of colonizers wherever there is a history of colonialism. This inequality, regarding who has access to the cultivation of plants for contemplation and appreciation, is a central tension in Kincaid’s novel Lucy.

Kincaid contrasts the orderly garden, a symbol of colonization, with the agricultural and medicinal uses of plants, which have historically been integral to the survival of the colonized. In both her novel and her garden writing, Kincaid presents an ancestral knowledge of plants as medicine. In “The Disturbances of the Garden,” Kincaid remembers the herbal teas her mother offered her as a child: “cups of barley water (that was for the measles) and…cups of tea made from herbs (bush) that she had gone out and gathered and steeped slowly (that was for the whooping cough)” (1). As Kincaid inherited a familiarity with herbs from her mother, Lucy carries similar memories in the novel. While awaiting a missed period, Lucy remembers the herbs which her mother taught her would “strengthen the womb,” or induce abortion (69). This information, passed from mother to daughter, is representative of plants as survival: the knowledgeable are able to reclaim their bodies from sickness or unwanted pregnancy, without having to ask permission of their oppressors. In this way, Kincaid reveals that medicinal plants provide the colonized and enslaved a form of personal freedom, while emphasizing the ways in which society’s neglect has forced descendants of Africans in the West Indies to protect themselves.

Throughout Kincaid’s novel, as Lucy tries to shake her connections to this past, her understanding of herbal medicine is one aspect of her memory she cannot suppress. Though she insists that the past is “the person you no longer are, the situations you are no longer in,” it is through plants that Lucy finds herself inextricably connected to her West Indies home (137). She is overwhelmed by “the smell of clove, lime, and rose oil,” plants her mother would steep, creating a protective bath to ward away evil spirits (124). Kincaid writes that experiencing this scent “almost made [her] want to die of homesickness,” creating a dichotomy between the healing nature of the plants and the excruciating weight of their cultural baggage (124). Kincaid reveals that an ancestral knowledge of plants, while rooted in healing, can also be an overwhelming connection to what has been lost through colonialism, and thus a painful reminder of cultural displacement.

For Kincaid, this displacement and homesickness is rooted in the garden. She writes in “The Disturbances of the Garden”: “It may be that my history, the history I share with millions of people, begins with our ancestor’s violent removal from an Eden. The regions of Africa from which they came would have been Eden-like, and the horror that met them in the ‘New World’ could certainly be seen as the Fall. Your home, the place you are from, is always Eden…and everything that happened after that beginning interrupted your Paradise” (6). Homesickness, which threatens Lucy with “[death] of longing,” may be so excruciating because it carries the weight of those who were displaced before her (91). Lucy’s ancestors, some of whom were taken to the West Indies as slaves, carried an unbearable homesickness. When Lucy migrates to the United States, she experiences a similar feeling: longing for the lost Eden of her childhood connects her to her ancestors’ loss.

When Lucy arrives to her host family in the United States, who live as “all the prosperous” do in a region with “four distinct seasons,” their relationships with plants surprise and irritate her (86). Most notable is her immediate desire to “kill” the daffodils which Mariah, her host mother, so admires. Though Lucy, a subject of the British Empire, was made to recite William Wordsworth’s poem “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud’” as a child, she was unlikely, as a citizen of the West Indies, ever to see the poem’s signature daffodils in person. Daffodils are suited to the temperate climate where “all the prosperous” live, and Lucy’s late introduction to them implies a lack of social mobility for Caribbean Americans, which fills her with rage. Lucy’s response to the daffodils is a reaction to the world of beauty and order that society has kept from her, under the unfair assumption that her life would be too centered on labor to indulge in the aesthetic beauty of the flowers.

When Lucy does see the daffodils, she is struck with the desire to cut them down with “an enormous scythe… at the place where they emerged from the ground” (29). Kincaid brings in the agricultural gesture of the scythe harvesting a crop, a gesture which calls upon Lucy’s agricultural past as the descendent of enslaved Africans. As Lucy narrates, “Nothing could change the fact that where she saw beautiful flowers I saw sorrow and bitterness” (30). Lucy carries the historical burden of her agricultural ancestors, an added trauma for an already marginalized person. Fusing the agricultural labor of the enslaved with the beautiful yet useless daffodils, Kincaid draws into focus the conflict between colonized labor and the contemplation of the colonizer.

While Lucy’s relationship to plants is rooted in survival and historical memory, other characters in the novel have a relationship with plants rooted in appearance—a relationship that lays bare the sharp contrast between colonizer and colonized. Mariah’s appreciation of the beauty of nature falls squarely within the dominant European tradition. She describes the daffodils as “curtsy[ing] to the lawn stretching out in front of them,” the word “curtsy” implying a European courtliness, beauty bowing to uniformity (17). Earlier, Lucy describes Mariah’s family as being like the daffodils themselves: they are “six yellow-haired heads of various sizes, as if they were a bouquet of flowers” (12). By describing the family as a bouquet of daffodils, Kincaid implicates the family in a homogenized culture where they are prized for their beauty at the expense of other, “weedier” lives. It is Mariah’s “pleasant” smell that reveals her privilege, while Lucy would prefer “a powerful odor” that could “give offense”(27).

This prioritization of aesthetics in nature contains a colonialist history. “The conquerors could do more than feed themselves; they could also see and desire things that were of no use apart from the pleasure they produced,” writes Kincaid in “The Disturbances of the Garden” (6). Seeing agriculture for its beauty is often a privilege afforded to those who delegate the labor to others. While Mariah looks out the window on freshly plowed fields and expresses her love for them, Lucy looks upon them and immediately connects them to someone’s labor: “Well, thank God I didn’t have to do that” (33). Lucy’s ancestors, some of whom were enslaved Africans, may have had to, and Lucy carries their suffering in her reaction to nature; European-American Mariah can afford to ignore this history in favor of aesthetics.

While this exoticism gives her a momentary power, it ultimately prohibits her from belonging to her environment, from being fully human. Kincaid shows that exoticization is the perverse appreciation of another’s appearance, valuing the aesthetically pleasing without acknowledging or allowing concealed trauma. Like Mariah and the fields in the previous paragraph, Kincaid’s image of the plants, trained in blue light, implies an insidious tidying-up of history to exclude slave labour and colonialist trauma from the dominant cultural narrative.

Though Kincaid uses plant imagery to bring a colonialist history into the present, she also seeks a postcolonial understanding of engagement with nature. Acknowledging the oppressive and painful colonial significance of plants and the garden, Kincaid uses Lucy to explore an alternative, where the title character can relate to plants on her own terms, and through her own senses. Kincaid writes in “The Disturbances of the Garden,” referring to the Biblical story of the garden of Eden, that horticulture is represented by the Tree of Knowledge, the tree of the forbidden fruit. In Lucy, we see the title character begin to engage with plants in an intuitive way, exploring her sexuality in a manner henceforth forbidden to her. In the process, she begins to reclaim both plants and herself from the narrative of domination previously discussed in this essay.

In Lucy, Kincaid develops a connection between fruit and sexuality which supports a metaphor of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. When Lucy tells the story of Myrna and Mr. Thomas, she describes their sexual encounters as taking place beneath a breadfruit tree. Breadfruit, as Kincaid writes in “The Disturbances of the Garden,” was planted in the West Indies by colonizers who “were concerned with the amount of time it took enslaved people to grow food to sustain themselves” (7). For Kincaid, then, this plant can be read as a symbol of the colonizer’s influence, an effort on their behalf to rob enslaved people of their time. That Myrna and Mr. Thomas seek shelter under the colonizer’s tree, stealing time to pursue their desires, is subversive in this context: Under the umbrella of a colonial system, individuals continue to evolve.

Throughout the novel, Kincaid develops this metaphor regarding the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, by arguing that colonized peoples have not been able to mature in their intellectual or sexual development. Early on in the novel, Lucy tells the story of Sylvie, a woman whose face is scarred from “a human-teeth bite… as if her cheek were a half-ripe fruit and someone had bitten into it, meaning to eat it, then realized it wasn’t ripe enough” (24). That same scar is described later as “a dark, purple plum” (25). From this point on, Lucy begins to associate coming of age with this secretive woman and her “forbidden fruit,” her scar a symbol of passion and violence. Sylvie, who Lucy admires for her mysterious sexuality, is only “half-ripe,” implying that she has not had the opportunity to develop herself to her fullest potential. Through the image of a plum representing sexuality, Kincaid returns to the Edenic concept of the “forbidden fruit,” which one must eat to achieve the knowledge of good and evil.

In Lucy, Kincaid also connects the plum image to another kind of knowledge. Returning later in the novel to the plum, Lucy remembers the plum tree that was cut down in her childhood yard “because one of my brothers had almost choked to death swallowing whole a plum he picked up from the ground” (131). The plum tree here may be seen as a metaphor for Lucy’s own education and development, which was cut short by the birth of her brothers. In the novel, Kincaid imagines the plum as the fruit from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, the “Knowledge of Good” represented by Lucy’s curtailed education, and the “Knowledge of Evil” by Sylvie’s “half-ripe” sexuality. Through these characters, Kincaid imagines an Eden in which Eve was never allowed the opportunity to discover “good” or “evil,” implying that the women in Lucy’s West Indies community were never allowed the opportunity to mature.

If the plum is seen as a metaphor for “the Knowledge of Good and Evil,” it is bitten while “half-ripe” or “swallowed whole,” never savored. A free exploration of one’s sexuality or self-exploration, like the freedom to plant and cultivate a garden of flowers, rests on an abundance of leisure not available to Lucy’s community under a colonialist system. Lucy later describes “bad sex” as “like wanting a sugar apple and getting a spoiled one,” evoking the horrible surprise of a fruit whose interior does not match its desirable exterior (114). Her struggle to fulfill her own sexuality, thereby partaking of the Tree of Knowledge, represents her effort to transcend the sexual repression and embedded gender roles of the colonialist society into which she was born. Lucy reclaims the imagery and experience of plants in service of this transcendence. In doing so, Lucy is repossessing the Garden, defining her own relationship with plants beyond what her colonial education has offered her.

Lucy also discovers a sensuality in the deconstruction of plants, loving their recklessness and celebrating her own. When Lucy sees the peonies which Mariah has put in a vase, she notes that she would like to “lie down naked and cover [her] body with these petals so [she] could smell this way forever.” This is a startlingly sensual response, starkly different from her reaction to the daffodils earlier in the novel. She comments that she “did not know a climate like this could produce flowers that bloomed… with such abandon,” implying both that the flowers, on some level, remind her of her home climate, and that she admires their wantonness (60). Unlike the daffodils, which her colonial education prepared her to admire in sterility, Lucy is able to admire the peonies authentically, celebrating their “abandon,” which is like her own. Lucy wishes to deconstruct the peonies, as she did the daffodils earlier in the novel. However, instead of destroying them, she wishes to bathe herself in their scent. Though this new sensuality regarding plants does not erase Lucy’s sense of a colonialist history, it liberates her as an individual to engage the world around her on her own terms.

In Lucy, we see that for Kincaid, the garden contains oppression and liberation at once. Kincaid shows the reader how plants present in our environment are informed by a colonialist history, one of forced migration and international trade, and also by the ethos of colonialism, wherein a gardener decides what is “valuable” versus what is considered a weed. Plants give Lucy (sometimes unwanted) access to her memory, “that haunting, invisible wisp that is steadily part of our being,” and to her inherited trauma (“Disturbances” 4). However, it is also through plants that Lucy begins to construct a new narrative, carving an empowered sexuality out of an undesired history. In this way, she begins to repossess her personal Garden of Eden, developing an understanding of self which is informed, but not inhibited, by her ancestors. Through her writing, Kincaid illuminates the garden as a microcosm of human history, and a gateway for individual growth.

Works Cited

Clark, William. A Mill Yard, On Gamble’s Estate, Antigua. 1823. Print. Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora. www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/1142. Accessed 10 May 2021.

Courbet, Gustav. Young Ladies of the Village. 1851–52. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/438820. Accessed 10 May 2021.

Ehret, George. Plantae Selectae: No. 37 – Yucca. 1735. Engraving. The Cleveland Museum of Art. www.clevelandart.org/art/1957.192. Accessed 10 May 2021.

Gauguin, Paul. Femmes de Tahiti, ou Sur la Plage. 1891. Oil on canvas. Wikimedia Commons www.commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Paul_Gauguin_056.jpg. Accessed 10 May 2021.

Kincaid, Jamaica. Lucy. Era, 2010.

Kincaid, Jamaica. “The Disturbances of the Garden.” The New Yorker, 31 August 2020, www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/09/07/the-disturbances-of-the-garden. Accessed 14 October 2020.

Köhler, Franz. Köhlers Medizinal-Pflanzen: Cassava. 1897. Wikimedia Commons, 26 January 2007, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Koeh-090.jpg. Accessed 10 May 2021.

Kratochvil, Paul. “Keukenhof Flower Gardens”. Photograph. Publicdomainpictures.net, https://www.publicdomainpictures.net/en/view-image.php?image=16460&picture=keukenhof-flower-gardens. Accessed 10 May 2021.

Woolmington, Robert E. Jamaica Kincaid in her Garden. Photograph. 1999. Andrea Gibbons, May 25 2020, http://www.writingcities.com/2020/05/25/jamaica-kincaid-breadfruit-gardens-empire/. Accessed 10 May 2021. © Robert E. Woolmington. Used with permission of the artist.

Recent Comments