In this essay, Lily Weber examines environmental injustice through the lense of democratic precarity. Weber swiftly employs the use of the Flint water crisis as the central case study for her piece, in order to demonstrate how the mismanagement of emerging environmental disasters can undermine democracy and the rights of Americans. While dissecting many scientific studies on the Flint crisis, Weber paints a clear picture of the government’s failure to act in a timely, effective manner, while highlighting the importance of protecting the people’s agency. –Nell Adkins ‘23, editorial assistant

The Flint Water Crisis: Environmental Injustice under a Flawed Democracy

Lily Weber ’25

Hair loss, rashes, bacterial infections, miscarriages, low birth weights—these are the symptoms that citizens of Flint, Michigan endured from using water contaminated with lead and other pollutants for 18 months (Pauli 5). This public health disaster became known as the Flint water crisis. The crisis occurred between April 2014 and October 2015, when Flint obtained water from the Flint River; prior to this period, Flint had been getting pretreated water from the Detroit Water and Sewer Department, or the DWSD (Davis, Appendix V). The improperly treated water from the Flint River corroded Flint’s pipes, leaching lead into the water supply (Stanley 1). The switch to the Flint River resulted from a series of decisions made by Flint’s emergency managers, appointed by governor Rick Snyder in response to Flint’s budgetary deficits (Fasenfest 37). Between December 2011 and April 2015, Flint had four emergency managers, who had the power to override the city council (Fasenfest 39; Jacobson et al. 569). Because residents of Flint had a limited voice in government under emergency management, this system violates the fundamental principles of democracy.

Merriam–Webster’s dictionary defines democracy as “an organization or situation in which everyone is treated equally and has equal rights.” Environmental justice is an application of democratic principles with regard to environmental decision-making. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race… with respect to environmental laws, regulations, and policies.” The foundation of democracy is the right of all citizens to have a voice in their government. Michigan’s government not only denied this right to many citizens, but disproportionately restricted democracy in Black communities—an infringement on democracy and environmental justice. The Flint water crisis resulted from a failure of the democratic process because the people did not have a say in the decisions that impacted their health.

The lead contamination in the Flint water supply happened needlessly because the government subverted democracy. Flint’s Black communities, in particular, suffered from the lack of a voice in government. Flint is a majority Black city, with Black people accounting for 54% of the population as of 2019 (“Flint, MI”). Citizens were denied a voice because Flint was governed undemocratically by emergency managers. Although the emergency managers are directly at fault for the crisis, the fundamental reason why Flint’s citizens were poisoned is because of the broader problem of environmental injustice, exemplified by the system of emergency management that betrayed the public interest.

How did water from the Flint River cause lead contamination? The river water is corrosive, meaning it wears away metals through chemical reactions (Chang and Goldsby). When corrosive water makes contact with pipes containing lead, the lead is released into the water (Clark et al. 714). Galvanized steel pipes are coated with a layer of zinc, which protects the steel from corrosion, and the zinc layer contains lead (Clark et al. 713). If copper pipes are upstream from galvanized steel, chemical reactions increase the amount of lead released (Clark et al. 714). Researchers Clark et al. showed that galvanized steel pipes can be a significant source of lead, with lead composing as much as 1.8% of the surface of the pipes (716). For reference, the EPA deems pipes used for potable water to be unsafe if the lead levels exceed 0.25% (Clark et al. 713). This Clark et al. study showed that concentrations of lead above the EPA’s action level can be released from galvanized steel pipes for years until the zinc coating is fully corroded (714). Benjamin Pauli of Kettering University in Flint notes that in summer 2014, corrosion caused lead in Flint’s water to exceed the action level by 5–6.5 times (2).

Corrosion released not only lead but also bacteria into the water supply (Pauli 2). To counteract the bacteria, Flint added excess chlorine to the water, which reacted with organic matter to produce carcinogenic trihalomethanes, or THMs (Pauli 2). In late 2014, the THM levels exceeded the standards set by the federal Safe Drinking Water Act. Corrosion control, such as chemicals called orthophosphates used to coat pipes, could have prevented this contamination (Pauli 2). Lead poisoning occurred because the government placed financial concerns over the needs of the citizens. In violation of the EPA’s Lead and Copper Rule, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) failed to implement corrosion control, perhaps because of the high cost; corrosion control would have cost Flint $140 per day (Jacobson et al. 556). Despite the water chemistry of the Flint River, lead exposure was not inevitable, but a symptom of a broader problem.

The lead crisis exemplifies the danger of a system that allows one individual to make decisions for a whole city. The crisis resulted from a series of poor decisions by Flint’s emergency managers. Before the crisis, from 1967 to 2014, Flint had obtained its water from the DWSD (Paine and Kushma 3), but in 2013, the city council of Flint voted to switch from the DWSD to the Karegnondi Water Authority (KWA), predicting a 25% decrease in cost (Stanley 34–35). The DWSD canceled its contract with Flint, but the Karegnondi pipeline would not be completed until 2016 (Paine & Kushma 3). Flint needed a temporary water source from 2014 to 2016, and Flint’s emergency managers, without approval from city council, chose the Flint River (Paine and Kushma 3).

Emergency manager Ed Kurtz authorized the switch, and his successor, Darnell Earley, allowed the decision to go through (Flint Water Advisory Task Force 40). Earley sold nine feet of the DWSD pipeline, despite city council’s vote against its sale (Fasenfest 40). Even after a year of lead-contaminated water, emergency manager Jerry Ambrose, Earley’s successor, entered into a loan agreement under the conditions that Flint could not return to DWSD water, citing reasons of affordability (Flint Water Advisory Task Force 40–41). Flint’s emergency managers bypassed democracy and reduced Flint’s city council to a figurehead. While the job of city council is to protect the citizens’ best interest, the emergency managers were allowed to disregard the citizens in favor of economic concerns. In this way, emergency management prevented Flint’s residents from having a voice in government.

While Flint’s individual emergency managers are at fault for switching to the Flint River, Michigan’s system of emergency management is also to blame for granting them disproportionate power. Researchers Jacobson et al. from the University of Michigan School of Public Health analyzed Michigan’s complex legal framework that allows the state government to displace local democracy. Their study reveals how emergency management overrides democracy. Under this system, the governor of Michigan can appoint an emergency manager to control a city’s finances if the governor determines that the city is in a financial crisis (569). This emergency manager is not elected by the people and thus has little incentive to act in the people’s interest (570).

Emergency management concentrates power at the state level instead of the local level, because the emergency manager reports to the governor rather than city officials (Jacobson et al. 569). An emergency manager’s decisions do not need to go through the city’s mayor or city council, and the people are powerless under an emergency manager, with no laws that allow them to appeal the emergency manager’s decisions (Flint Water Advisory Task Force 42). The emergency manager laws assume that local elected officials are incapable of remedying their city’s financial situation (Flint Water Advisory Task Force 41). While the emergency managers did not violate a specific law in jeopardizing public health (Jacobson et al. 569), morally, they should have considered the health impacts of obtaining water from the Flint River. A democracy should protect not only the economy but, more importantly, environmental justice.

Governor Snyder, who vowed to take a businesslike approach to government (Paine & Kushma 4), allowed his emergency managers to run Flint like a business rather than a democracy. In his piece The Emergency Manager: Strategic Racism, Technocracy, and the Poisoning of Flint’s Children, Jason Stanley, Professor of Philosophy at Yale University, argues that Snyder and his emergency managers used Flint to accomplish one of their main business goals: privatization (37). All of Flint’s emergency managers made decisions that favored private corporations over the public (Fasenfest 40–41). These decisions included a 50% tax break to General Motors in contrast with a reduction in the salaries and retirement benefits of city employees (Fasenfest 41). This sympathy toward corporations and disdain for the public eventually contributed to the lead crisis.

Stanley argues that besides the supposed cost-effectiveness, an underlying motive for switching Flint’s water away from the DWSD was the hope that losing Flint as a customer would push the DWSD into debt (38). Weakening the DWSD would open it up for purchase by a private company, such as the transnational water management corporation Veolia (Stanley 38). Once Flint had left the DWSD, Veolia was hired to analyze Flint’s water quality (Stanley 38). Veolia, however, had a conflict of interests: to keep the DWSD in a vulnerable position, Veolia had a motivation to prevent Flint from returning as the DWSD’s customer (Stanley 38). Veolia, therefore, manipulated its analysis and deemed Flint’s water to be safe (Stanley 38). By ordering residents’ taps to be shut off if they could not afford the water, Kevyn Orr, emergency manager of Detroit, had already primed Detroit’s citizens to think of water as a commodity rather than a public good, and thus to accept the privatization of the DWSD (Stanley 37). Orr’s economic philosophy outweighed the cruelty of denying citizens a life-sustaining resource, an action contrary to the values of environmental justice. A functioning democracy prioritizes the welfare of the people, whereas Michigan’s government prioritized its business interests.

Like Orr, Flint’s emergency managers also made water a less accessible resource. According to Stanley, during Flint’s period of emergency management, water rates increased dramatically (34). Between 2005 and 2009, Flint’s residents paid, on average, $27.17 per month for water (Stanley 34). In 2013, after rate increases under emergency managers Michael Brown and Ed Kurtz, Flint’s monthly water rates more than doubled to $59.37 (Stanley 34). In comparison, Ann Arbor, MI, similar in size to Flint, experienced water rates of only $13.76 per month in 2016 (Stanley 34). Rather than serving the needs of the citizens, these rate increases made water inaccessible to those who can’t afford it, cutting off their access to this essential resource.

Flint’s decision to switch to the KWA was likely impacted by a conflict of interests (Stanley 36). In an email to state and local officials, emergency manager Kurtz, intentionally vague, said “he felt like” the KWA pipeline would cost less than the DWSD, but a report by the engineering firm Tucker, Young, Jackson, Tull, Inc. proved that even at the astronomical water rates, staying with the DWSD would have been cheaper (Stanley 35–36). Kurtz had likely been influenced by Jeff Wright, the CEO of the KWA, and Rowe Engineering, the company in charge of building the pipeline (Stanley 35–36). Kurtz advocated for the KWA without considering health impacts, and he sidelined the public interest. Flint’s emergency managers burdened the citizens with exorbitant water bills, and manipulated the city into an agreement with the KWA that would lead to lead exposure. Notably, these decisions were made behind the scenes without involvement of the citizens.

Emergency management disproportionately affected Michigan’s majority Black cities. From 2009 to 2017, only 10% of Michigan’s white population—but 50% of the Black population—lived under emergency management (Fasenfest 35; Jacobson et al. 571). Between 2008 and 2013, nine Michigan cities were placed under emergency management: five majority Black cities and four majority white (Stanley 24). This distribution seems equitable, but the populations of the five majority Black cities, and the proportions by which Black people are in the majority, are much greater than the populations of the four majority white cities and the proportions by which white people are in the majority (Stanley 24).

Lead contamination, high water rates, and a limited voice under emergency management are only some of the hardships faced by Flint’s residents, particularly the Black population. Another example is the systematic dismantling of Black neighborhoods, like St. John’s on the north side of Flint, which has been an ongoing problem (The Black/Land Project 15). Residents of St. John’s endured water pollution caused by the General Motors factory, housing regulations that denied them mortgages, and a decline in housing value—yet more ways the citizens have been denied a voice (The Black/Land Project 15).

In the spirit of democracy, the citizens of St. John’s petitioned officials about their grievances, but after a decade of complaints, the government only responded by putting resources into housing elsewhere in Flint and building the highway I-475 to choke St. John’s off from the rest of the city (The Black/Land Project 15). Through these actions, combined with the installation of emergency managers in Flint and other majority Black cities, the government ignored the needs and voices of Black communities.

Emergency management denied agency to Michigan’s Black population not only at the municipal level through displacing city democracy but also at the individual level through cutting government jobs. To reduce spending, Flint’s first emergency manager, Michael Brown (predecessor of Ed Kurtz), fired almost 1 out of every 6 city employees (Fasenfest 40). These cuts disproportionately affected Flint’s Black population; in Michigan, 1 in 5 Black people works in a government position, 30% more than the amount of white government employees (Fasenfest 42). This decision follows the pattern of emergency management prioritizing finances over the welfare of the citizens. Clearly, the water crisis is not an isolated example of the government disregarding the needs of the people, or of Black communities bearing the majority of the suffering.

Emergency management kept Flint’s Black community in a disadvantaged position. Researchers Julie Sze and Jonathan London argue that governments are responsible for environmental injustice through distributing environmental risks and resources unevenly based on race (1332). For example, Native Americans disproportionately live near military bases and other polluted areas because of forced relocation by the government (Sze and London 1341). Similarly, Michigan’s uneven distribution of emergency management in majority Black cities follows the pattern of restricting the autonomy of underprivileged groups, which can lead to public health problems, as demonstrated by the water crisis.

Stanley argues that under fair circumstances, Flint never should have required emergency management (33). Michigan fabricated the financial distress in Flint and other cities by cutting state revenue sharing (Stanley 33). Between 2006 and 2012, Michigan reduced the revenue it gave to Flint from $20 million to $7.9 million—a decrease of 61%—so that the governor could justify installing an emergency manager (Stanley 33). The Michigan government took advantage of the existing vulnerability of Black communities to achieve its business goals. When local democracy might interfere with the governor’s plans—for example, to privatize the DWSD—the governor might find it convenient to override democracy, and democracy is most easily subverted in a majority Black city whose citizens have been historically underprivileged. The state’s takeover of Flint via emergency management exemplifies environmental injustice because the government denied democracy to Black communities.

The Flint lead crisis resulted from many layers of fault. The direct blame falls on the emergency managers, who made the decision to switch Flint’s water source from the Detroit Water and Sewer Department to the Flint River. To place all the blame on Brown, Kurtz, Earley, and Ambrose, however, would be to overlook the corruption and racism of the system that granted these emergency managers their power. Flint’s citizens drank and bathed with lead-contaminated water because the state government stripped Flint of its democracy. Governor Snyder and his emergency managers betrayed their duty to the public good in favor of their business interests, and made decisions that unevenly impacted Black communities. Michigan has ample freshwater—the Great Lakes contain 21% of the world’s supply (Stanley 10)—but that resource is useless if not protected by a functioning democracy. The system of government in Flint deprioritized the citizens’ health. The lead crisis occurred because Flint’s flawed democracy prevented citizens from advocating for their needs. As climate change exacerbates environmental problems, it becomes more critical that all people have the agency to make informed decisions about environmental resources—and governments must protect that agency.

Works Cited

Barera, Michael. “The Flint River in Flint, Michigan (United States.” Wikimedia Commons, 2 July 2018, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flint_July_2018_22_(Flint_River).jpg. 27 Sept 2022.

Black/Land Project. Beyond Fields and Factories: Black Relationships to Land and Place in Flint. Black/Land Project, 2012.

Chang, Raymond, and Kenneth A. Goldsby. Chemistry. McGraw Hill Education, 2016.

Clark, Brandi N., et al. “Lead Release to Drinking Water from Galvanized Steel Pipe Coatings.” Environmental Engineering Science, vol. 32, no. 8, 13 Aug 2015, 713–21, https://doi.org/10.1089/ees.2015.0073. 27 Sept 2022.

Davis, Matthew M., et al. Final Report. Flint Water Advisory Task Force, 21 Mar 2016, 39–42.

Fasenfest, David. “A Neoliberal Response to an Urban Crisis: Emergency Management in Flint, MI.” Critical Sociology, vol. 45, no. 1, 28 Aug 2017, 33–47, https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920517718039. 27 Sept 2022.

“Flint, Michigan Population 2020 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs).” World Population Review, https://www.worldpopulationreview.com/us-cities/flint-mi-population. 27 Sept 2022.

Jacobson, Peter D., et al. “The Role of the Legal System in the Flint Water Crisis.” The Milbank Quarterly, vol. 98, no. 2, 28 Apr 2020, 554–80, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12457. 27 Sept 2022.

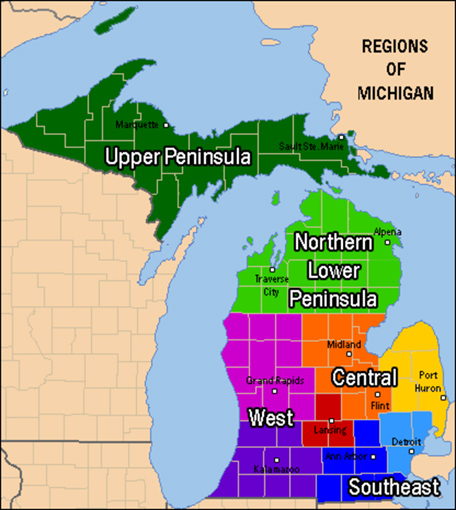

Michi906 (wikimedia commons user). “Regions in Michigan.” Wikimedia Commons, 16 Feb 2014, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Flint_Water_Crisis.jpg. 27 Sept 2022. 27 Sept 2022.

Nobles, Shannon. “Flint residents protest outside of the Michigan State Capital in January 2016.” Wikimedia Commons, 26 Jan 2016, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Michi906#/media/File:Michigan_Regions.png. 27 Sept 2022.

Paine, Mark, and Jane A. Kushma. “The Flint Water Crisis and the Role of Professional Emergency Managers in Risk Mitigation.” Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, vol. 14, no. 3, 28 Nov 2017, https://doi.org/10.1515/jhsem-2017-0009. 27 Sept 2022.

Pauli, Benjamin J. “The Flint Water Crisis.” WIREs Water, vol. 7, no. 3, 12 Mar 2020, https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1420. 27 Sept 2022.

Stanley, Jason. “The Emergency Manager: Strategic Racism, Technocracy, and the Poisoning of Flint’s Children.” The Good Society, vol. 25, no. 1, 1 May 2017, 1–45, https://doi.org/10.5325/goodsociety.25.1.0001. 27 Sept 2022.

Sze, Julie, and Jonathan K. London. “Environmental Justice at the Crossroads.” Sociology Compass, vol. 2, no. 4, July 2008, 1331–54, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2008.00131.x. 27 Sept 2022.

US EPA. “Environmental Justice.” 6 Feb. 2019, https://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice. 27 Sept 2022.

Recent Comments