In this essay, Annika Galvin critically utilizes an environmental justice framework to bring attention to the ways in which climate change compounds the harms of the prison industrial complex upon frontline communities. They crucially examine the ways in which this structural violence is intentionally enacted, for example, how prisons are often deliberately placed near toxic waste facilities. Galvin then advocates for solutions that center themselves around the concept of “prison ecology,” emphasizing an approach that is both intersectional and abolitionist in its vision. With urgency and insightfulness, Galvin dares us to dream of a better world—one based in communal care and solidarity, rather than carcerality and exploitation. –Yena Perice ‘26J

Mass Incarceration, Toxic Waste, and Systemic Injustice: An Underexplored Intersection

Annika Galvin ’27

In the United States, our criminal justice system relies upon mass incarceration as the predominant strategy for managing societal violence—a strategy deeply intertwined with the history of slavery and systemic racism. Historically and presently, our laws and policies disproportionately target marginalized and minority communities, facilitating their entry into the prison system for offenses that are often deemed minor or nonviolent. But mass incarceration is not only a racial justice issue, but an environmental one as well.

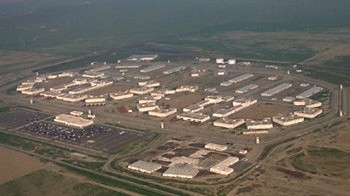

The environmental problem traces back to industrialization and the subsequent rise of capitalism, during which a disproportionate number of industrial and toxic waste sites were situated in communities of color and low-income neighborhoods (Taylor 34). This sequence of intentional malpractice further expands when considering the placement of prisons. Mounting evidence highlights systemic bias when penitentiaries are sited and constructed near federal Superfund and other hazardous sites, exposing incarcerated individuals to environmental injustices (Bradshaw 7). The intertwined nature of environmental injustice and the prison system has notably expanded since the prison boom of the 1980s (Davis 17). Proposed solutions have often revolved around the concept of “prison ecology” within anti-prison environmental movements, which emphasizes an intersectional and abolitionist approach to address both environmental and social injustices. Envisioning a future without mass incarceration provides the opportunity to reimagine society as more community-oriented, less driven by capitalist imperatives, and more focused on restoring justice for marginalized communities and incarcerated individuals. This abolitionist perspective not only offers insights into reshaping approaches to environmental justice, but also fosters a deeper connection between society and the environment, emphasizing the importance of communal harmony with the natural world.

The framework of environmental justice (EJ) brings attention to the disproportionate harm done to marginalized communities. Social and criminal justice advocate Elizabeth A. Bradshaw defines EJ as “the fair treatment and meaningful inclusion of all groups of people, particularly minority, low-income and indigenous populations, in the environmental decision-making process” (Bradshaw 4). The injustices committed against these populations become clearer than ever when viewing the US prison system through the lens of EJ, since systemic inequalities affect both the communities around prisons and the inmates themselves. Using an EJ framework to analyze prisons forces us to confront the intersection of white supremacist and capitalist systems, helping us corroborate the findings of social scientists who describe jails as “melting pots where these oppressive forces meet” (Ahmad 7). Racial minority populations are particularly affected by mass incarceration, which is made more noticeable by the growing number of jails and prisons. These communities are constantly caught in the center of systemic injustice.

Recognizing the long history of violence perpetrated in the US against people of color is crucial, because the glaring realities of systemic discrimination and the lingering effects of previous policies persist, despite strides toward legal equality (Kaba 48). This is felt especially strongly when it comes to the siting of industrial plants, waste processing facilities, and other environmentally hazardous institutions. Wealthy, majority white neighborhoods wield influence to strongly oppose these hazardous facilities being close to their homes; an occurrence known as the “Not in my backyard” (NIMBY) effect (Merriam-Webster 1). As a result, lower-income neighborhoods that are predominately made up of people of color bear the brunt of these burdens. Partly due to this, race emerges as the “strongest predictor” of the locations of toxic waste sites, which starkly exposes environmental injustices—or, perhaps more appropriately, environmental racism. Studies conducted as far back as 1987 reveal the startling prevalence of toxic waste sites in neighborhoods populated mainly by Black or Hispanic residents (Taylor 36). Living near such environmental dangers has significant consequences on all facets of communal life, from contaminated food and water to tainted air.

The siting of prisons in the United States mirrors this pattern of environmental injustice. The 1980s to 2000s saw a rise in the construction of prisons, most of which are located, like toxic waste sites, in rural areas with marginalized populations; these facilities disproportionately target communities of color, especially Black men in Southern states and Latino men in California (Eason 4). Paradoxically, the establishment of prisons was first embraced by these rural towns as a way to boost the local economy. But the wealth that was promised turned out to be short-lived, sending these communities into a downward spiral of reliance on the prison business. During the prison boom, social services helping low-income rural America drastically decreased while prison construction increased (Huling 3). While AFDC (Aid to Families with Dependent Children) spending was reduced by over $2 billion, government spending on corrections increased by almost $8 billion nationally. States thus started allocating 42% more of their funds to incarceration than to income assistance for low-income families (Huling 5). This only exacerbated the cycles of poverty and incarceration. The troubling association between jail sites and low-income, predominately BIPOC communities highlights a pattern of systemic injustice that has persisted throughout US history. The intersection of environmental and carceral injustices further exposes a complicated network of intertwined oppressions that keep vulnerable populations in cycles of poverty, pollution, and incarceration, all while denying them access to resources.

The inherent connection between siting prisons and siting toxic waste facilities comes down to the common, yet complicated hydra heads of systemic racism. These two factors compound when we consider the combination of prisons being placed near toxic waste or industrial disposal sites—a much more common occurrence than one might think. Examples of these environmental injustices range from mild issues to life threatening. The Abolitionist Law Center and the Human Rights Coalition uncovered concerning rates of severe health issues at the Fayette State Correctional Institution in Labelle, PA. These health problems are largely attributed to the presence of a nearby toxic coal waste dump, comprising approximately 40 million tons of waste, two coal slurry ponds, and millions of cubic yards of coal combustion waste (Dannenberg 2). A growing number of inmates have reported declining health, exhibiting symptoms consistent with exposure to toxic coal waste, including respiratory, throat, and sinus conditions; skin irritation and rashes; gastrointestinal tract problems; pre-cancerous growths and cancer; thyroid disorders; as well as other symptoms such as eye irritation, blurred vision, headaches, etc. (Russell 24). Incarcerated individuals in the US are already deprived of a number of their legal and human rights: inmates are forced into labor with minimal to no pay, stripped of their privacy, free speech, voting rights, and much of their individuality (Davis 24). It shouldn’t come as a surprise that the EPA’s environmental justice policies tend to ignore the plight that prisoners face. Despite the stark reality that most prisoners are predominantly people of color and low-income across all 50 states, and constitute the most vulnerable and burdened demographic in the nation, the Human Rights Defense Center (HRDC) has identified no indications of the EPA acknowledging this population or intending to address their unique circumstances (Bradshaw 4).

On top of this, despite the previously mentioned reallocation of funds from social services to prisons, prisons remain severely underfunded, further exacerbating issues with pollution, health problems, and unjust conditions. This leads to environmental health problems being created as a result of improper prison management—not only affecting inmates, but also the communities surrounding correctional facilities. The renowned legal news website, Prison Legal News, routinely notes how “crumbling, overcrowded prisons and jails nationwide are bursting at the seams—literally—leaking environmentally dangerous effluents not just inside prisons, but also into local rivers, water tables and community water supplies” (Dannenberg 1). This further emphasizes the inherent and complicated intersection between prisons and inmates, toxic waste sites, and the communities that surround them.

Prison abolition, or the general abolitionist movement, has a real and powerful ability to address these problems within our carceral system. An abolition ecology method envisions alternatives by facilitating the discovery and examination of harms inflicted or aggravated by racist carceral regimes to ecosystems, humans, and non-humans alike (Stephens‐Griffin 6). For instance, we can gain a deeper understanding of the connections between environmental issues and the current justice system by looking at the effects of our mass-imprisonment system, and the part it currently plays in environmental degradation and supporting harmful systemic practices (Tsolkas 3). Understanding this intersection makes the connection between systemic inequalities and environmental problems more obvious, highlighting the stark injustice that was previously shrouded by our current justice system.

But prison abolition is more than just a movement to dismantle the system. It has a more comprehensive plan for changing society: fundamentally, abolitionism aims to eliminate oppressive institutions and systems while also imagining and constructing alternatives that are based on equality, justice, and liberation. This unique approach allows everyone to have a say and form institutions that are mutually fair and beneficial for all. Abolition itself comes with an environmentalist lens; dismantling the state and its systems inherently means to dismantle not just our current justice system, but also our current capitalist economy and the government that encourages it. For the wellbeing of all living things, an abolitionist ecology understands that resolving the systemic injustices and inequalities that the carceral system perpetuates is necessary to achieve environmental justice. Abolitionist ecology provides a way forward for social change and environmental sustainability by elevating the perspectives and experiences of disadvantaged communities and promoting comprehensive, restorative approaches to justice (Stephens‐Griffin 4). Going hand in hand with environmentalism as a concept, we must understand that abolition calls for a communal society based on mutual respect and relations with each other, as well as with the natural world around us.

Dismantling the current system means actively recognizing how harmful it is to societal systems and natural systems alike; an abolitionist imagination gives us the ability to see how to operate outside these current systems (Kaba 158). If done thoughtfully enough, by including perspectives of all who live and operate within our country, we can create a new society that operates within environmentally sustainable limits, all while making a justice system based on accountability rather than carceral punishment. This not only can solve the problem of hazardous waste facilities and prisons being disproportionately sited in marginalized communities, but nearly all of the social, environmental, and economic problems that arise from it. Building an abolitionist society that is environmentally sustainable is essential. By eliminating oppressive structures and placing a higher priority on sustainability, justice, and equity, abolition ecology leads to a more fair, just, and sustainable future for everybody by embracing environmental stewardship, responsibility, and mutual respect.

Works Cited

Ahmad, Nadia. “The Cliodynamics of Mass Incarceration, Climate Change, and ‘Chains on Our Feet.’” Fordham Urban Law Journal, vol. 49, no. 2, Feb. 2022, pp. 371–400.

Bradshaw, Elizabeth A. “Tombstone Towns and Toxic Prisons: Prison Ecology and the Necessity of an Anti-Prison Environmental Movement.” Critical Criminology, vol. 26, no. 3, July 2018, pp. 407–22, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-018-9399-6.

Dannenberg, John. “Prison Drinking Water and Wastewater Pollution Threaten Environmental Safety Nationwide | Prison Legal News.” www.prisonlegalnews.org, 15 Nov. 007, www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2007/nov/15/prison-drinking-water-and-wastewater-pollution-threaten-environmental-safety-nationwide/.

Davis, Angela. Are Prisons Obsolete? Seven Stories Press, 2003.

Eason, John. “Understanding the Effects of the U.S. Prison Boom on Rural Communities.” Institute for Research on Poverty, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Nov. 2019, www.irp.wisc.edu/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Focus-35-3c.pdf. Accessed 16 Apr. 2024.

Huling, Tracy. “Prisons as a Growth Industry in Rural America.” Static.prisonpolicy.org, 16 Apr. 1999, static.prisonpolicy.org/scans/prisons_as_rural_growth.shtml. Accessed 16 Apr. 2024.

Kaba, Mariame, and Andrea J. Ritchie. No More Police. The New Press, 2022.

Merriam-Webster. “NIMBY.” Www.merriam-Webster.com, www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/NIMBY. Accessed 2 Sept. 2024.

Russell, Kelsey. “Cruel and Unusual Construction: The Eighth Amendment as a Limit on Building Prisons on Toxic Waste Sites.” University of Pennsylvania Law Review, vol. 165, no. 3, Feb. 2017, pp. 741–83.

Stephens-Griffin, Nathan. “Embracing ‘Abolition Ecology’: A Green Criminological Rejoinder.” Critical Criminology, vol. 31, Nov. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007 /s10612-022-09672-7.

Taylor, Dorceta E. Toxic Communities : Environmental Racism, Industrial Pollution, and Residential Mobility. New York University Press, 2014.

Tsolkas, Panagioti. “The Ecology of a Prison Nation.” Proquest.com, Earth First, June 2015, www.proquest.com/docview/1692912030?accountid=13911&sourcetype=Magazines. Accessed 16 Apr. 2024.

Recent Comments