Whitin’s essay unflinchingly considers the current restoration work the Seminole Tribe of Florida is doing on the Florida Everglades as a tribe that was forced off of their original land, forced to inherit the Everglades, and is now being forced to work on said restoration work alongside the White Settlers who are destroying the Everglades. Bolstered by extensive research, Whitin offers an informed take on the essentiality of the Everglades to the Seminole who consider the wellbeing of the land and its wildlife as integral to the wellbeing of the Seminole themselves. This is all framed by an outspokenly self-reflective note at the start of the essay that situates the author as a White Settler both raised and living on Indigenous land, and encourages readers to consider how their own perspective may impact the way in which they read the essay. –Mars Sell ‘26

The Impact of Seminole and Settler “Inheritance” in the Everglades and the Future of South Florida, Humankind, and the World

Whitin ’27

Note: For clarity, I am a White settler who grew up on Seminole and Timucua lands. I now live on Nonotuck ancestral homelands. After listening to Indigenous people, I better understand that no paper can be free of bias, since no human can. I hope the reader takes the time to consider how my and their own perspective affect the experience of reading this paper. While we cannot be free of bias, we can be as reflective as possible: please visit the bibliography to this paper to find sources written by indigenous persons, aside from learning from your own research.

The word “Inheritance” is not a perfect word for this title. It can imply purposeful and comfortable passing along. However, the story of how the Seminole found a home in the Everglades is one of centuries of violence. The word also implies an element of choice. The first people to inhabit the Everglades did not choose who got to inherit their niche in the ecosystem, or to leave their niche at all. “Inheritance” also implies the common colonial concept of ownership, a value which, when projected on the Everglades, has caused the ecosystem an unfathomable amount of trouble. This is why I make the distinction that modern humans have taken on a niche rather than inheriting the Everglades itself. A niche is a term in ecology that describes the specific role an organism, in this case, humans, plays in its environment, the Everglades. This word places humans as just one part, or in ecological terms, one functional group, of the overall community and greater ecosystem.

“Inheritance”, however, is a useful word for this title. It implies that what is being passed down is of value. The term also effectively encapsulates the grief that ties to the past and the hope that ties to the future.

Inheritance is a process that illuminates how human history in the Everglades has resulted in our modern struggles. The process of inheritance is complicated, as the human niche is shared between all humans in South Florida. Particularly, inheritance has been uniquely different for indigenous peoples and white settlers, resulting in the parallel inheritance of distinctly different perspectives. In order to make effective change in South Florida, settler colonizers must acknowledge the history of the distinct and tumultuous processes of inheritance, how this creates both the ongoing colonial assumption that the Everglades are conquerable without consequence, and the Seminole views of the Everglades that they are a vital aspect of their cultural identity and an advantage in resisting colonialism. As a result, Seminole authority in decisions over environmental issues plays a driving role in the popular movement to “Save the Everglades.” In order to take on this task, one that many might deem to be impossible, the Seminole’s demands must be valued as unique and vital results of the overall processes of inheritance of the human niche.

Emerging Perspectives through Inheritance

The Everglades is home to a variety of ecosystems, has incredibly high biodiversity, and provides clean drinking water and protection from hurricanes for almost 10 million Floridians. It is a place Homo sapiens are lucky to have been a part of for millenia. The effects of the role, or “niche,” that Homo sapiens play in the Everglades has changed as the inheritors of the niche have changed. The first humans in the Everglades built canals, reservoirs, shell mounds, seawalls, dams, and fish traps, and therefore directly and indirectly influenced their ecosystem (Grunwald 18-22). Unlike today, they did not transform them enough to make them completely unrecognizable. Although most of these indigenous peoples had been wiped out from war, violence, and disease in the early 16th century, especially by Spanish colonizers, in the modern day, new inheritors of the human niche have changed how Homo sapiens take on their ecological roles in the Everglades. Importantly, these inheritors include the Seminole, who are descendants of many, including the early indigenous people in Florida, as well as from other tribes in the southeast (The Seminole Tribe of Florida, b).

The differing processes of inheritance are highlighted in the Seminole Wars. The Seminole Tribe of Florida explains how the Seminole identity, including the name, was developed as colonialism in the US developed: “it became something more, a common identity that united people from disparate backgrounds, but who had a common cause and faced a common invading enemy. It was with pride they then called themselves Seminole” (The Seminole Tribe of Florida, b).

Although the tribe first mostly lived in South Georgia, this changed with the Seminole Wars–brutal, devastating conflicts that took place from 1817 to 1858 (Dixon). While the US government considers there to be three wars, many Seminole believe there was only one, drawn-out conflict (The Seminole Tribe of Florida, b). The First Seminole War resulted in the U.S. military pushing the Seminole people to live nearer the Everglades, an area they had previously used for hunting (Dixon).

The Second Seminole War was instigated by Andrew Jackson’s signature on the Indian Removal Act. The act was created with the goal of forcing all remaining indigenous people in the eastern United States to the west, including the Seminole (Dixon). To the Seminole, the west, being the direction of the setting sun, was also the direction of death; they refused to be pushed around by colonizers and they were fiercely determined to keep their adopted home (Grunwald 37-38). With far less manpower and resources, they fought the U.S. by using both their inherited knowledge of the Everglades and the inherited strength in their identity to their advantage (The Seminole Tribe of Florida, b).

The third war consisted of more continued violence by the US military, including the implementation of concentration camps (The Seminole Tribe of Florida, b). One of these camps was located on Egmont Key, which is now disappearing due to environmental change. “It’s one of many examples of the pain and suffering we had to endure just to be here today,” says Quenton Cypress of the Wind Clan (“Egmont Key”). By the end of the wars, which the Seminole proudly never signed a peace treaty to end, about 300 Seminole people were left to take refuge in the Everglades, where they would remain until today, eventually becoming a federally recognized tribe in 1957 (Dussias 235). Despite their frequent relocations forced by industry and the government’s various drainage projects and highway constructions cutting through Seminole land, the Seminole population grew exponentially throughout this time (Knight 271).

The Seminole Wars mark an early example of how both groups of people inherited different views of the Everglades, a difference that would complicate the inherited relationship between Homo sapiens and the Everglades and entangle humans in the fate of South Florida. The Seminole’s process of inheritance first allowed them to use the Everglades as bountiful hunting grounds, then a sanctuary, and then an advantage in war. For hundreds of years, a healthy Everglades gave the Seminole sustenance, resilience, and identity. Today’s Seminole people understand themselves as closely related to the “other-than-human” parts of South Florida and many view direct impacts on the health of the Everglades as impacts on the tribe itself (LaDuke 47-64). So, as the Seminole inherited their role as humans in the Everglades, the way in which they occupy this role is heavily influenced by their inherited interpretation of the Everglades.

In contrast, the Everglades have always been an enemy to the White settlers. A government report issued a decade before the First Seminole War described the Everglades as “suitable only for the haunt of noxious vermin, or the resort of pestilent reptiles” (Grunwald 4). Colonizers fought for the Everglades simply because they believed they had a right to the land and only found “use” for the Everglades once they had transformed it (Grunwald 39). In a way, they viewed the Seminole people and the Everglades similarly: as dark, foreboding entities to tame and conquer (Grunwald 35-39). As settler colonizers inherited the human niche in the Everglades, their continuing destruction of the landscape is fueled by their inherited disdain for the Everglades as an unfarmable, unnavigable, and unlivable landscape (Grunwald 35-39). To colonizers, the “other-than-human” world is separate from them. Their ability to take control is what signifies their power and health. Simultaneously, white settlers and the Seminole inherited the shared human niche in the everglades while inheriting distinct perspectives. These inherited beliefs influence modern perspectives greatly and therefore impact how Homo sapiens, as a functional group, are willing and able to make change in their environment.

Modern involvement of the Seminole: Expressions of Inheritance

The processes of inheritance are ongoing, and the Seminole people’s inherited perspectives of the Everglades are seen in their actions today. The Seminole are composed of three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Tribe of Florida, the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians in Florida, and the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma (“Seminole Nation …”). The Seminole people also compose themselves of eight clans, each of which shares characteristics with a unique non-human being including Panther, Bear, Deer, Wind, Bigtown, Bird, Snake, and Otter (“Seminole Nation …”). It is important to remember that all Seminole individuals have their own opinions, as well as each group.

The Independent Traditional Seminole are people of Miccosukee and Seminole heritage that are not enrolled in either federally recognized tribe of Florida, but are “the traditional Seminole governing body” that challenge the US and local government with their “open land claim” that they had their lands illegally taken from them so they have all rights to use Florida land as the see “fit for their people” (“Independent Traditional Seminole Nation of Florida Letter”). They make powerful assertions that the government and corporate exploitation of the Everglades must cease (LaDuke). The Panther Clan of the Independent Traditional Seminole, in particular, draw parallels between their struggles and the decline of the panther population, stressing the interconnectedness of their cultural preservation and the well-being of the panther (LaDuke 63). Winona LaDuke (Ojibwe) writes that “Both the panther and the Seminole have fought for their land, and they intend to remain there” (47). The Panther Clan criticizes human interventions aimed at studying panthers, advocating for non-interference to allow natural regeneration. Its members argue that environmental degradation, caused by urban development and pollution, adversely affects both panthers and their community’s health. Bobby Billie of the Panther Clan says, “It’s no different with our people. Our natural world is disappearing. Our habitat, our foods” (LaDuke 64). The Independent Traditional Seminole see themselves in the panther in this way too: both would have been better without the White Man’s destructive inventions (LaDuke 63-4). This sentiment reflects a broader concern about the disappearance of the Everglades, which highlights the interconnectedness between the Seminoles’ cultural preservation and the well-being of the Everglades ecosystem.

When it comes to the panther, the Panther Clan states, “the cat’s fate will likely depend on the goodwill of the orange growers and ranchers in southwestern Florida” (LaDuke 64). However, the corporations in South Florida will not stop or help with restoration unless they, or the government that regulates them, listens to the Seminole and takes action. Much like the Seminole Tribe of Florida, the Independent Traditional Seminole struggle with being perceived as corrupt, since the Seminole Tribe’s casinos stain the colonial imagination that pictures a morally pure Indigenous person (LaDuke 57). This way of thinking, that requires indigenous peoples to fit certain stereotypes to be viewed as valid by White people is one of the many ways colonial narratives attempt to take power from or erase indigenous identities. So, while it needs to be made clear that the Seminole tribes are not responsible solely for the restoration of an ecosystem they are forced to share their niche of, it is necessary that the broad movement to “Save the Everglades” needs to center Seminole concern, first, out of respect for the Seminole identity and, second, if the movement has any chance to be successful. The views on panther population restoration between both the Panther Clan of the Independent Traditional Seminole and the very same government who played a significant role in endangering the animal are just one example of how the ways in which the human niche in the Everglades is inherited leads to consequential tensions.

The Seminole Tribe of Florida is also involved in Everglades conservation, facing challenges as their waterways have been drained and polluted, hunting grounds taken, and homes affected by the actions of the White settlers (Dussias 234-235). The tribe has several “task forces, working groups, and commissions” that are dedicated to the preservation and restoration of the broader Everglades ecosystem (The Seminole Tribe of Florida, d). This conservation work is vital as it is done both as a result, in spite of, and in collaboration with the White settlers the Seminole people share the niche with. The Seminole people have inherited their perspectives, as seen by the processes of their inheritance of their niche in Florida. This means for the Seminole, broadly, the Everglades is a part of their identity as it is deeply tied to their history, and they are able to accomplish pivotal work because of their unique perspective. Water, in particular, is integral to both the identity and health of the tribe and the wetlands. Issues around water have spurred major legal pursuits for protection since the 1980s (Dussias 239). Water quality standards at the Big Cypress and Brighton Reservations resulted from these pursuits and are vital measures to ensure the protection of surface and groundwater quality (Dussias 240). The Director of Water Resources of the Seminole Tribe explains that the tribe’s efforts to maintain traditional practices are also threatened by Everglades disappearance and climate change impacts (Swiersz 53).

The Seminole Tribe views their Everglades restoration projects as means of preserving their tribe, since their livelihoods are deeply connected: “if the land dies, so will the Tribe” (Dussias 240). To protect and restore natural resources, the Seminole have partnered with federal, state, and regional agencies, often the exact same agencies that have been actively taking land from the Seminole tribes in order to harm the Everglades. For instance, the Seminole Everglades Restoration Initiative, a collaboration between the tribe and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), is a multi-year program aimed at improving water quality (The Seminole Tribe of Florida, e). Despite collaboration with agencies like the USACE, however, challenges persist, as seen in disputes over collaborative projects and water management (Staletovich). The Seminole Tribe of Florida’s efforts to restore natural hydrology, protect water quality, and engage in intergovernmental initiatives underscore the importance of tribal involvement in environmental conservation for the benefit of both the tribe and the broader ecosystem. This relates not only to how inheritors conflict over environmental resources, but also how this inherited conflict results in resources being allocated now in a courtroom–what the Seminole Tribe of Florida views as its current battleground, where they are vigorous defenders for their sovereignty (The Seminole Tribe of Florida, b). Homo sapiens in South Florida all simultaneously inherited their conflicts over the same niche and their perspectives that are a product of ongoing violence. If we cannot understand our struggles to be a sustainable functional group in South Florida as a product of our personally unique inheritances, we will never be able to move forward with lasting and impactful change. The Seminole Tribe of Florida names their goal to repair “a broken system of relationships, and healing the land and ecosystems we depend on” (“Services”). To understand this goal, understand the history that contextualizes the tension between our species and between our species and our environment.

Impacts of Inheritance

As important inheritors of the human niche, the Seminole Tribes of Florida live in an Everglades forever changed by setter exploitation. The patterns that the processes of inheritance take throughout history continue today. The same government that has continuously threatened the Everglades and the Seminole people’s relationship to the Everglades is the same government that attempts to take on restoration projects. As stated by the Seminole Tribal Historic Preservation Office, “We have learned from our forefathers about the losses of our people in the Seminole War, and during recent years have witnessed the coming of the White man into the last remnant of our homeland” (Dussias 234). The Seminole are forced to partner with the very same people that “drain our lakes and waterways, cultivate our fields, harvest our forests, kill our game, and take possession of our hunting grounds and homes” in order to “Save the Everglades” (Dussias 234-5). All the while, despite a long history of their own disregard of the Everglades, White settlers still ignore the Seminole people’s necessary perspective. It is an issue of settlers not understanding or caring why they will always make impossibly inadequate saviors.

The relationship between humankind and the Everglades began when the ecological niche was first occupied by humans before Spanish colonization. These first human occupants maintained themselves as a part of their ecosystem at sustainable levels of impact while manipulating their surroundings. Their Traditional Ecological Knowledge, TEK, of the Everglades is not gone, it lives on in the inheritance of modern humans. The Seminole Tribe of Florida intends to create a sustainable future by creating strategies that harness both western methods of science and TEK (“Services”). Despite this, the Seminole are still often excluded from decision-making on the Everglades.

In the Second Seminole War, the colonizers nearly lost to the Seminole, despite having far more resources, because they underestimated the power of TEK. Then, the colonizers waged war against the Everglades, and they are close to losing again. As mentioned in Grunwald’s book, “The Everglades is a test…. If we pass, we may get to keep the planet” (8). If colonizers continue to ignore TEK, and their lack of it as a result of their inherited perspective, they are close to losing this test, and this war. “It is our responsibility to uphold knowledge about the original stewards of this land,” said Mitzi Carter during a speech at Florida International University, where she encouraged supporters of restoration projects in the Everglades to take into account indigenous perspectives (Ramos). The Everglades is a “test” because it will show if we can achieve Robin Wall Kimmerer’s (Potawatomi) dream of giving more than we take from ecosystems, so that “when we rise to give thanks to the forest, we may hear the echo in return, the forest giving thanks to the people” (Kimmerer, 150).

The state of the Everglades challenges us to understand the dark and violent history of our inheritances. Homo sapiens inherited their niche in the invaluable ecosystem of the Everglades, an ecosystem that provides necessary water, biodiversity, and wonder. If we, as White settlers, understand there are people before us that influence us and people after us that we will influence, as inheritance is designed, how would that change our treatment of our environment, including the Everglades? If we, as Homo sapiens, understand that the processes of inheritance in South Florida matter, we are forced to collectively realize our hopes for the future relationship between the Everglades and humankind. If this relationship is preserved, humanity may also be.

Works Cited

Cammauf, Rodney. “Florida Panther.” NPGallery, November 24, 2022, 17afa03e-845a-4ac8-bd7c-6902129ff13f.

Chimney, Michael J., and Gary Goforth. “History and Description of the Everglades Nutrient Removal Project, a Subtropical Constructed Wetland in South Florida (USA).” Ecological Engineering 27, no. 4, 31 October, 2006: pp. 268–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2006.05.015.

Cooper, Brittany. Cromwell Day Speech. Given at Smith College on 2 November, 2023.

Dixon, Letticia. “Seminole: People.” Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Seminole-people Accessed 13 December, 2023.

Dussias, Allison M. “The Seminole Tribe of Florida and the Everglades Ecosystem: Refuge and resource.” FIU Law Review, vol. 9, no. 2, 2014, https://doi.org/10.25148/lawrev.9.2.7.

“Egmont Key.” Seminole Tribal Historic Preservation Office, The Seminole Tribe of Florida, stofthpo.com/egmont-key/. Accessed 3 October 2024.

Florida State Parks. “Mound Key Archeological State Park: History”. FloridaStateParks. https://www.floridastateparks.org/parks-and-trails/mound-key-archaeological-state-park/history#:~:text=Mound%20Key%20is%20rich%20in,food%20was%20easy%20to%20find. Accessed December 2, 2023.

Grunwald, Michael. The Swamp: The Everglades, Florida, and the Politics of Paradise. Simon & Schuster, 2007.

“Independent Traditional Seminole Nation of Florida Letter.” https://Parkplanning.nps.gov/Document.cfm?DocumentID=29997, National Park Service.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall, Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses. Corvallis, OR, Oregon State University Press, 2003.

Knight, Henry. “‘Savages of Southern Sunshine’: Racial realignment of the Seminoles in the selling of Jim Crow Florida.” Journal of American Studies, vol. 48, no. 1, Feb. 2014, pp. 251–273, https://doi.org/10.1163/2468-1733_shafr_sim080200047.

LaDuke, Winona. “Seminoles: At the Heart of the Everglades.” All Our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life, Haymarket Books, United States, 2017, pp. 45–71.

Liestman, Jim. “Sunset at 10,000 Lakes NWR, Florida.” Flickr, August 8, 2019, www.flickr.com/photos/gods-art/47938143993/in/dateposted/.

Link, Reinhard. “Big Cypress National Preserve, South-Florida.” Flickr, December 29, 2015, https://www.flickr.com/photos/129472585@N03/16138305182/in/photostream/.

National Wildlife Federation. “Protecting the Everglades.” National Wildlife Federation, https://www.nwf.org/Our-Work/Waters/Great-Waters-Restoration/Everglades#:~:text=The%20Everglades%20are%20essential%20for,Florida%27s%20%241.2%20billion%20fishing%20industry. Accessed December 14, 2024.

Ramos, Laura Lopez. “The Land We Are On.” FIU News, Florida International University, 6 Oct. 2022, news.fiu.edu/2022/the-land-we-are-on.

The Seminole Tribe of Florida a. “Government: How We Operate.” Semtribe, www.semtribe.com/government/introduction. Accessed 2 October 2024.

The Seminole Tribe of Florida b. “History” Semtribe, www.semtribe.com/history/introduction. Accessed 2 October 2024.

The Seminole Tribe of Florida c. “Seminole Tribe of Florida: Home.” Semtribe, www.semtribe.com/stof. Accessed 25 October 2023.

The Seminole Tribe of Florida d. “Services: What We Provide: Environmental Resource Department.” Semtribe, semtribe.com/services/environmental-resource-management-department. Accessed 2 October 2024.

The Seminole Tribe of Florida e. “Tribal Water Code of the Seminole Tribe of Florida.” Tribal Water Code, January 1995.

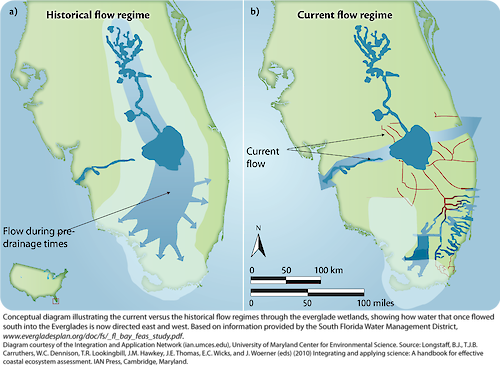

Thomas, Jane. “Historical versus current flow regime through the Everglades wetlands: A comparison of the current water flow in the Everglades (East to West), versus the historically North-South flow.” Integration and Application Network, January 1, 2010, historical-versus-current-flow-regime-through-the-everglades-wetlands.

“Seminole Nation: The Unconquered People.” Blog.nativehope.org, Native Hope, 23 Oct. 2023, blog.nativehope.org/seminole-nation-the-unconquered-people.

“Services” Heritage and Environment Resources Office – Sustaining Tribal Legacies, Seminole Tribe of Florida Heritage and Environment Resources Office, Apr. 2020, stofhero.com/hero-services/. Accessed 3 Oct. 2024.

South Florida Water Management District. “Everglades”. SFWMD. https://www.sfwmd.gov/our-work/everglades#:~:text=Because%20of%20efforts%20to%20drain,rich%20plant%20and%20wildlife%20community. Accessed 17 December 2023.

Staletovich, Jenny. “Stand-off between Indian Tribes and Army Engineers Threatening to Derail Everglades Restoration Work.” WGCU PBS & NPR for Southwest Florida, WGCU, 11 May 2020, news.wgcu.org/2019-10-30/stand-off-between-indian-tribes-and-army-engineers-threatening-to-derail-everglades-restoration-work.

Swiersz, Sarah. “Sea-Level Rise and Climate Justice for Native Americans and Indigenous Peoples: An Analysis of the United States’ Response and Responsibilities.” STARS, University of Central Florida, stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/805/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2023.

Weisiger, Marsha. “Indigenous peoples and the environment since 1890.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.1104.

Recent Comments