Imagine there was a farm lived by animals and they were oppressed by their human owner, they all gathered to reach a resolution that they will overthrow their human leader. They succeeded in their coup d’etat mission and they overthrew him. It was time for the animals to appoint their new leader within the farm. There were two prominent pigs, Snowball and Napoleon, and they started to represent their ideas to the animals so that they could be voted for. Snowball was in favor of reducing labor, generating electricity, and overall improving the farm conditions, while Napoleon opposed this plan. It was the election day as Snowball was about to win, nine terrifying dogs sent by Napoleon started chasing him off of the farm. Since Snowball got expelled, Napoleon was appointed as the head of the farm.

Though this story may appear to be just a simple tale, it is actually a reflection of real events from the Russian Revolution and the rise of the Soviet Union. The key characters symbolize significant political figures from that period, bringing history to life through allegory. Therefore, can we truly understand the depth of a story if we strip away its meaning in pursuit of pure experience? Animal Farm is a political allegory that reflects the events of the Bolshevik Revolution and the subsequent betrayal by Joseph Stalin. Instead of directly addressing key political figures and crises at that time, Orwell uses animals- most notably pigs-as alternatives for the central characters in the Union Soviet Socialist Republican (USSR). Through this creative approach, the story explores themes of power, corruption, and betrayal, using the farm and its inhabitants to represent the larger political landscape in a way that is both subtle and deeply symbolic. An example that both supports and challenges Sontag’s thesis is Animal Farm, a satirical allegorical novella. The story’s allegory, along with the emotional and sensory experience it evokes requires interpretation of both its form and content to fully grasp its meaning.

Furthermore, focusing too much on Animal Farm’s political meaning might take away the direct experience and emotions we might have with the book. It may diminish the empathy, the feeling of sadness, and exasperation for those oppressed animals. Therefore sometimes in “a place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art”(Sontag, 10). Directing attention excessively on the allegory of the Russian Revolution and Stalinism may cause us to overlook the story’s emotional depth and sensory experience. Instead we need “an erotics of art”, connecting with the sensation, deep feeling and affection of the story. For example, rather than seeing Boxer (a loyal hard working horse in the farm), as the exploited proletariat or the working class, “an erotics of art” invites us feel the tragedy of this used innocent horse and the feeling of agitation of Napoleon’s betrayal and brutal actions.

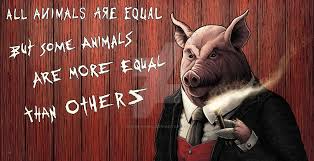

However, Animal Farm highlights how content and allegory are fundamental and crucial to the work’s meaning. The content of the story- animals overthrowing and rebelling against their human oppressor in hope for equality mirrors- the subvert of the Russian revolution and also the rise of the Soviet Union. Thus, it is the allegorical form that gives the story a powerful multi-layered impact. At times, it’s essential to uncover the deeper meaning and fullest context within a story, unlike Sontag’s argument that we need to “cut back all content”(Sontag, 10), and enjoy the sensory experience of the work to the fullest. However, Animal Farm asserts that the story’s meaning is inextricably linked to its political symbolism. The rebellion of the animals is not just an emotional narrative, but a reflection of real historical events—the overthrow of the Russian leader Tsar Nicholas II symbolizing Mr. John, and the prominent leaders of the ascent of the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin and Leon Trostsky representing Napoleon and Snowball. This perspective emphasizes that the story’s multi-layered impact comes specifically from its allegorical structure, where content (political meaning) is very essential. Therefore comprehending the allegory is crucial for grasping the full significance of the story, and the meaning lies in the fusion of the political content with the animal characters’ struggles.

Moreover, George Orwell exemplifies how satire, through a careful balance of “form” and “content” creates a powerful critique of political ideologies . We must both rely on the form and content of the tale, creating a seamless interplay that enhances the depth and effectiveness of Orwell’s satirical message. If readers didn’t dig “behind the text”, how would we “find a sub-text which is the true one””(Sontag, 4). George Orwell’s use of satire in Animal Farm demonstrates how form and content combine efforts to complete the full meaning of a work. Orwell’s satire isn’t just a stylistic choice but a way to deliver a criticism message of political ideologies, making it mix humor with biting social commentary allows readers to engage with complex political issues in a more accessible and impactful way.

In Conclusion, Without interpretation, we may lose the opportunity to engage deeply with art that challenges us to think critically about society, power, and human behavior. And a lot of times authors write about their identity and the situation they have lived through. In Orwell’s case, he couldn’t freely express in writings about his political views or beliefs, due the political censorship of his time. Using allegory and satire was a way for Orwell to freely express what he wanted people to know but not in an explicit way. By crafting narratives that resonate on multiple levels, Orwell found a way to convey the urgency of his message without facing the dire consequences of overt dissent. Therefore as readers it’s our duty to dig behind, think beyond, and outside of the box to ‘find [the] subtext which is the true one”(Sontag, 4). This process not only enriches our understanding of the work but also fosters critical thinking that encourages us to question and analyze thoughtfully of the world around us. Engaging with literature in this way transforms reading into an active dialogue, where we can grapple with the complexities of existence and the pressing issues that shape our societies. If art could provide both alluring pleasure and moral insights, how can we balance between both experiences?

Work Cited

Sontag, Susan. “Against Interpretation.” Against Interpretation, Picador, 1966, pp. 1-

10.