By Alina Yildirim ’26

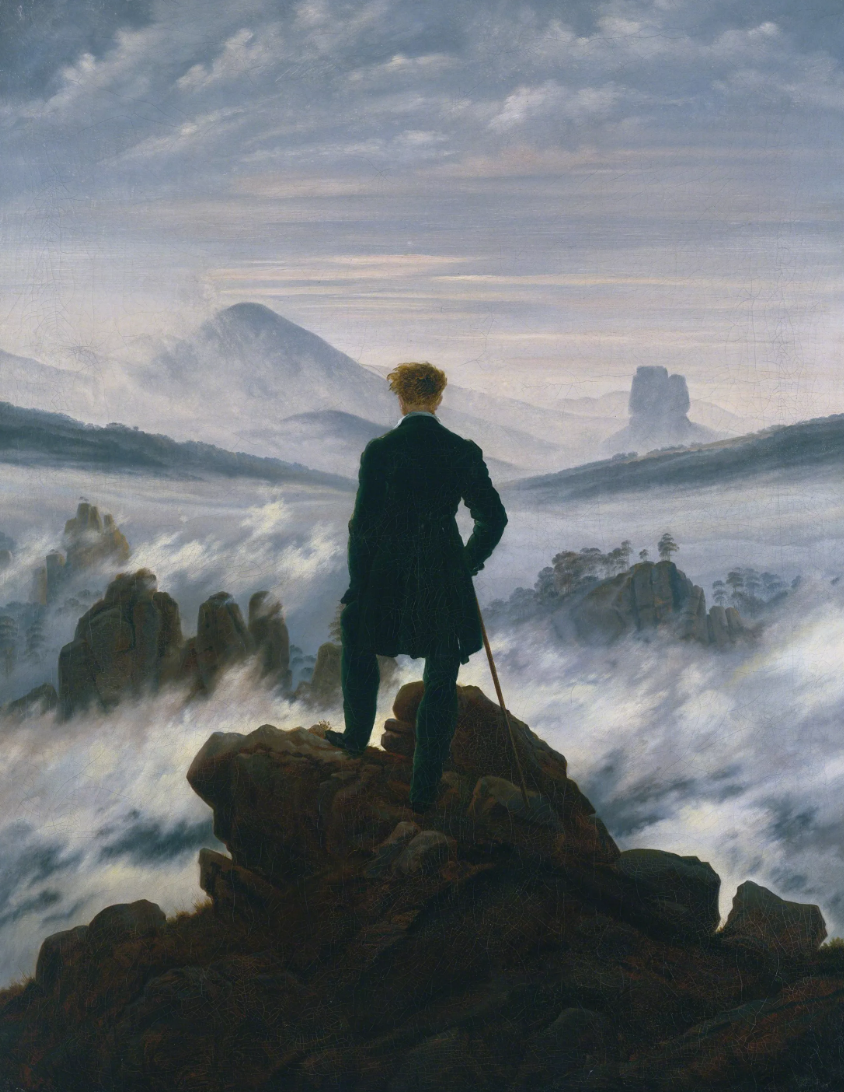

Imagine being asked to analyze a painting, not for its colors, composition, or the immediate feelings it evokes, but to unravel its hidden messages and symbolic meanings. This was often the case when interpreting Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, a painting that became a subject of study in combination with Four Sea Interludes by Benjamin Britten in German music classes. Instead of allowing the viewer to appreciate the dramatic contrast between the lone figure and the surrounding fog, the focus shifted to what the fog might symbolize or how the figure’s posture represented some deeper human struggle. In such moments, the raw, emotional power of the artwork seemed to fade, overshadowed by layers of analysis. This aligns with Susan Sontag’s argument in Against Interpretation, where she states that art’s true value lies in its sensory and visual impact rather than hidden meanings (Sontag 5). Friedrich’s painting exemplifies this idea, offering a profound experience that resonates deeply when it is allowed to speak for itself, free from the burden of over-interpretation.

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog draws viewers in through its striking perspective, offering a view that places them alongside the lone figure overlooking a sea of fog. The viewer stands with the figure, feeling the weight of the landscape stretching out before them, a scene that is both peaceful and inspiring. From this point of view, the painting creates a sense of being on the edge of something vast and mysterious, where the sky and fog blend into each other. The contrast between the dark figure and the light background highlights this reflective moment, as if the whole world stops for a breath. The experience is not about uncovering what the fog might represent or what the figure’s posture means; rather, it is about the quiet power of the scene itself—the feeling of standing above the world. This aligns with Sontag’s idea that art should be appreciated for its immediate, visual presence. As she notes, “What matters in Marienbad is the pure, untranslatable, sensuous immediacy of some of its images” (Sontag 6), emphasizing that art’s true value lies in its ability to create a direct, sensory response in the viewer. In Sontag’s view, art is most powerful when it affects us through its form and surface, without being overanalyzed. In Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, the viewer is invited to engage directly with what they see—to feel the mood of the scene, without needing to interpret every element. Sontag’s perspective suggests that this type of direct engagement allows the painting to speak for itself, offering an experience that resonates deeply through its visual power alone.

Some argue that interpreting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog for hidden meaning enriches its appreciation, making it more intellectually engaging. As part of my music studies in high school, I was required to interpret this piece because it is associated with Four Sea Interludes by Benjamin Britten. The fog could symbolize uncertainty, or the lone figure could represent humanity’s journey through the unknown. While this approach can add a layer of intellectual depth, it often distracts from the direct, sensory experience of the painting, which I found frustrating. The painting has a powerful presence that should be appreciated for what it is—its colors, its mood, its composition—rather than looking for meanings that may not have been intended. Susan Sontag criticizes such over-interpretation, stating, “Interpretation is the revenge of the intellect upon art” (Sontag 4). Focusing on potential symbolism takes attention away from the painting’s immediate impact, turning the experience into an intellectual exercise rather than a sensory one. Instead of feeling the scale and atmosphere of the scene, viewers get caught up in decoding possible meanings, missing the opportunity to experience the painting’s true visual power.

Friedrich’s painting invites viewers to engage with it through sight and emotion, perfectly aligning with Sontag’s idea that art should be felt through the senses, not overanalyzed. Sontag emphasizes, “Our task is not to find the maximum amount of content in a work of art, much less to squeeze more content out of the work than is already there” (Sontag 10). The simplicity of the scene—the lone figure standing quietly against the fog—creates an immediate connection with the viewer. It evokes feelings of awe and wonder simply through its serene composition, without needing complex interpretation. The vast, open landscape invites viewers to feel the scale and atmosphere of the painting, to get lost in the fog and sky, and to experience the isolation and calm that the scene offers. This sensory experience draws attention to the present moment, allowing viewers to absorb the quiet beauty of the scene without the distraction of searching for deeper meanings. The straightforward presentation of the figure and the fog encourages viewers to connect with the scene on a purely emotional level. Sontag’s perspective supports this approach, suggesting that art should be an encounter with what is right in front of us, rather than an intellectual puzzle to solve. In Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, the focus is not on interpreting symbols but on experiencing the painting’s mood, its colors, and its quiet majesty. This direct engagement allows the painting to resonate more deeply, offering a moment of calm reflection as the viewer stands metaphorically beside the lone figure, facing the vast unknown. By appreciating the simplicity of Friedrich’s scene, viewers can connect more deeply with the artwork itself. It is in this simplicity that the painting’s true impact is found—not in deciphering hidden meanings but in feeling the atmosphere it creates.

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog exemplifies the power of art to resonate through its form and sensory impact alone, without the need for symbolic interpretation. Reflecting on my own experience, the requirement to analyze the painting during my music studies often distracted from the simple pleasure of viewing the artwork and experiencing its emotional impact directly. Susan Sontag encourages us to enjoy art for its immediate, sensory experience instead of thinking about it too much. This method not only enhances our engagement with art but also preserves its intrinsic beauty. By focusing on the visual and emotional qualities of art, rather than searching for hidden meanings, we open ourselves to more profound experiences of awe, wonder, and emotional connection. In doing so, we allow art to truly speak for itself, demonstrating that sometimes, the most profound engagement comes from simply experiencing art as it is.