https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.20366.html.

The Project

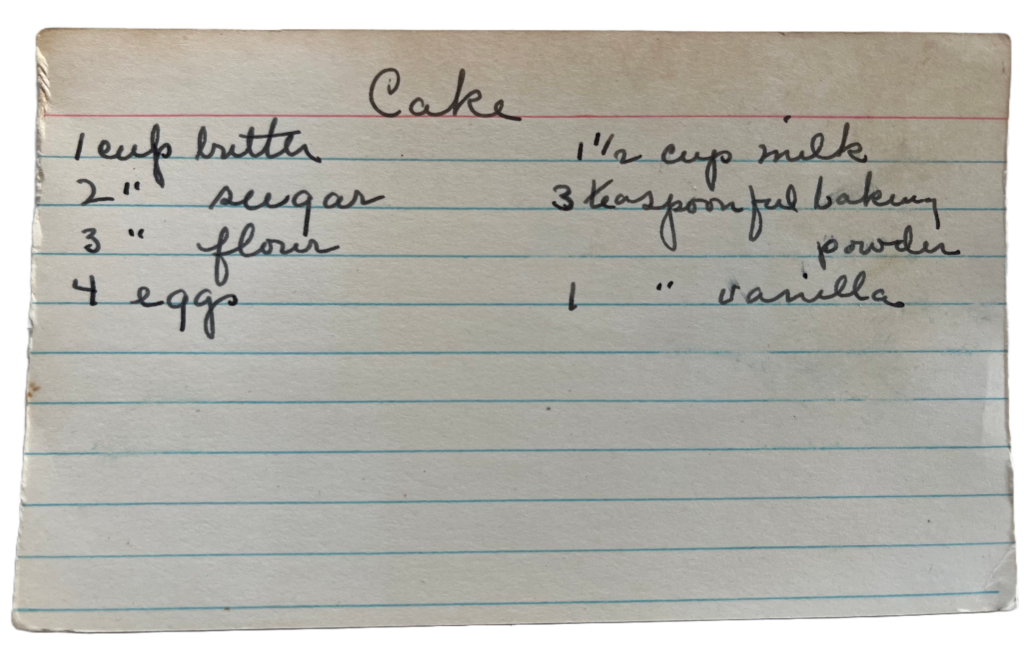

This project was born out of my curiosity for the women of the past – how did they live their lives and what were their experiences? It links the women within my own family to the social, political, and economic changes that occurred between 1865 and 1915 regarding the domestic sphere and “women’s work”. What drove my research was the interest in what my relatives and other women like them thought about during their day-to-day activities and how they perceived their own place in the world. What threads could I find that linked them to me – the answer to that lay in my family’s collection of recipe cards, dating back to my great-great-great-grandmothers, all of whom were born during the Civil War. As they came of age in the 1880s and created households of their own, often with, in my opinion, way too many children, did they think back to how their mothers had been, the food they had made, and the customs they followed? By tracing the creation of the American housewife, we see the concentration of thought regarding gender, race, and the socio-political economy distilled into the women who ran their houses from their kitchens and inhabited a yet-unexplored space: the middle class.

The women of my family who embody the lived experiences of this history represent a fraction of the stories that exist and are by no means meant to be taken as an all-encompassing example. They were part of both middle to upper-middle-class households, and as such, had the opportunity to create their own histories and leave evidence behind. It is essential to remember that this white, middle-class generation of women that came of age following the Civil War often could and did hire a variety of help, despite the fact that working-class young women were increasingly seeking employment elsewhere. As such, the principle of “the American housewife” is a racialized ideal that was not extended to African American women, Native women, or any ethnic minority; “household management” literature catered to this class of white women learning to navigate a new socio-economic status that relied on them performing the duties of wife, mother, and manager of those employed in her home.

That food was a vehicle for these changes centers my project within home kitchens and with the women who had the privilege and ability to record their lives through the food they both prepared and consumed. The recipes of my family most likely have complicated histories involving labor and from whom, but the tradition of passing culinary knowledge from one generation to another remained. It is this direct line of domestic ideology that I am interested in – how were these women understanding their work within the home, and how was that transposed upon their daughters, if it was at all? The formation of the American Housewife, therefore, required some necessary ingredients: a burgeoning white middle-class, concerns about urbanization and maintenance of cultural knowledge, and a new understanding of what it meant to be a woman that was directly connected to her ability to sustain her home through food.

The Curator

Clare McElhaney

Smith College Class of 2023

This website and its accompanying exhibition, located at the Nielson Library on the Smith College campus from April to August 2023, are my Senior Capstone Project for my Archives Concentration.

I have always loved history, particularly finding and bringing to light stories and people previously overlooked, obscured, or otherwise unknown. This project fits well within my focus on Women’s History and fulfills my nagging desire to know more about the women in my family and their lives in comparison to my own.

“Semi-Rural Kitchen and Dining Room, 1910.” Perkins Harnly, c. 1935-1942. National Gallery of Art.

Citation for Home Screen Image

Sources

Works Cited

Chavasse, Pye Henry, and Sarah Hackett Stevenson. Wife and Mother, or, Information for Every Woman. Chicago: H. J. Smith & Co., 1888. SSC-MS-00391, Box 5, Families Collection. Sophia Smith Collection of Women’s History, Smith College.

Inness, Sherrie A. Dinner Roles: American Women and Culinary Culture. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2001.

Inness, Sherrie A., ed. Kitchen Culture in America: Popular Representations of Food, Gender, and Race. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

Neuhaus, Jessamyn. Manly Meals and Mom’s Home Cooking: Cookbooks and Gender in Modern America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003.

Walden, Sarah. Tasteful Domesticity: Women’s Rhetoric & The American Cookbook, 1790-1940. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2018.

Mrs. Beeton’s Every-Day Cookery, London: Ward, Lock & Co., Limited, 1907. SSC-MS-00392, Box 3, Folder 5, Miscellaneous Subjects Collection: Cookery. Sophia Smith Collection of Women’s History, Smith College.

The American Housewife and Kitchen Directory, New York: Dick and Fitzgerald, Publishers, 1869. SSC-MS-00392, Box 3, Folder 3, Miscellaneous Subjects Collection: Cookery. Sophia Smith Collection of Women’s History, Smith College.

Works Consulted

Deutsch, Tracey. “Home, Cooking: Why Gender Matters to Food Politics.” In How History Matters to Contemporary Food Debates, edited by Charles C. Ludington and Matthew Morse Booker, 208-227. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

Folbre, Nancy. “The Unproductive Housewife: Her Evolution in Nineteenth-Century Economic Thought.” Signs 16, no. 2 (Spring 1991): 463-484.

Goodsell, Willystine. “The American Family in the Nineteenth Century.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 160, no. 1 (March 1932): 13-22.

Parloa, Maria. First Principles of Household Management and Cookery: a Text-Book for Schools and Families. Cambridge: H. O. Houghton and Company, 1879.

Shapiro, Laura. Perfection Salad: Women and Cooking at the Turn of the Century. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1986.

Sharpless, Rebecca. “Cookbooks as Resources for Rural Research.” Agricultural History 90, no. 2 (Spring 2016): 195-208.

Theopano, Janet. Eat My Words: Reading Women’s Lives through the Cookbooks They Wrote. New York: Palgrave, 2002.