Please read the full statement about the inherently racial nature of “housewife” as a term and occupation at the bottom of the page.

“There is no subject which should occupy the attention (…) comparable with that of food and its influence of human progress.”

Ellen Richards, as cited in Sarah Walden, Tasteful Domesticity: Women’s Rhetoric & the American Cookbook, 1790-1940 (Pittsburg: University of Pittsburg Press, 2018), 114.

6 October 1862

Mary Eulalie “Eula” Green, my great-great-great-grandmother, is born.

8 October 1863

Rosa Gilmour Arrington, my great-great-great-grandmother, is born.

27 November 1864

Irene Jones, my great-great-great-grandmother, is born.

1865: The End of the Civil War

The economy of the Civil War led to “new innovations in canning and preserving” through packaging food for both soldiers and civilians and the increasing availability of glass “mason jars.”1 Resourcefulness and “thrift” – making something out of very little – became a source of pride and accomplishment, instilling the notion in many middle-class women that domestic labor “had a certain dignity.”2 They were called upon to fulfill their “domestic duty”: to serve the nation through the family. This domesticity was espoused to white middle-class women who received this image alongside the ability to hire domestic servants; embracing this “duty” and the “primary responsibility of their sex” was therefore broken along class lines.3

Image: Crosse and Blackwell Advertisement Card, circa 1870-1900.4

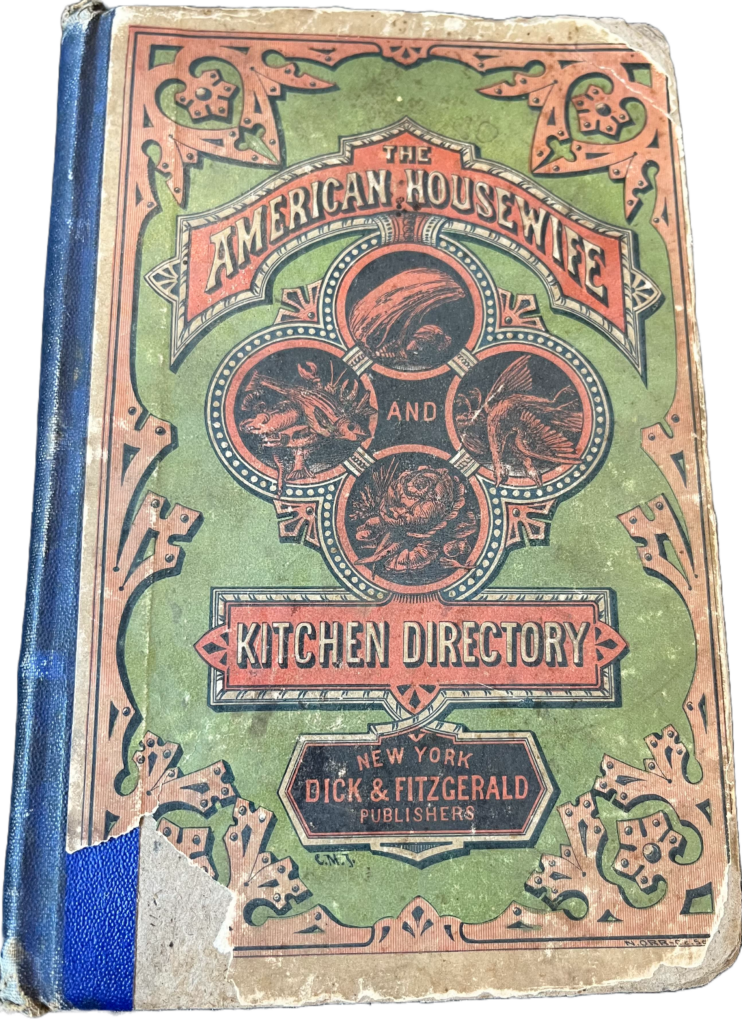

1869: The American Housewife and Kitchen Directory

“Containing the Most Valuable and Original Receipts, in All the Various Branches of Cookery; Together with a Collection of Miscellaneous Receipts and Directions Relative to Housewifery” completes the very long title of this book. The unnamed writer states that her goal is to “[produce] a Cook Book which shall commend itself to all persons of true taste – that’s to say, those whose taste has not been vitiated by a mode of cooking contrary to her own.”5 She makes several references to “good American housekeepers” to whom this book will be a welcome “practicality” as she bemoans the “inefficiency” of other publications. She also establishes her authority on the subjects contained therein by stating that she “has endeavored to combine both economy and that which will be agreeable to the palate (…) but has never suffered the former to supersede the latter.”6

1870s: The Arrival of Cooking Schools

This part of the “domestic science revolution” centered around the “intensifying concern of the middle and upper classes about urbanization and immigration”7. Informal teaching continued, but the need was identified for formalized culinary education. Cooking schools, often located in urban centers such as New York began offering cooking classes and domestic service training to both middle-class women and working-class women, although the two differed in what they focused on. Middle-class women “consulted cookbooks to assist them with more elaborate meals and attended fashionable cooking classes” while working-class women were targeted to reform their “food habits”; this was not an altruistic notion – it signified a goal to “Americanize” recent immigrants and “reform” different culinary traditions.8

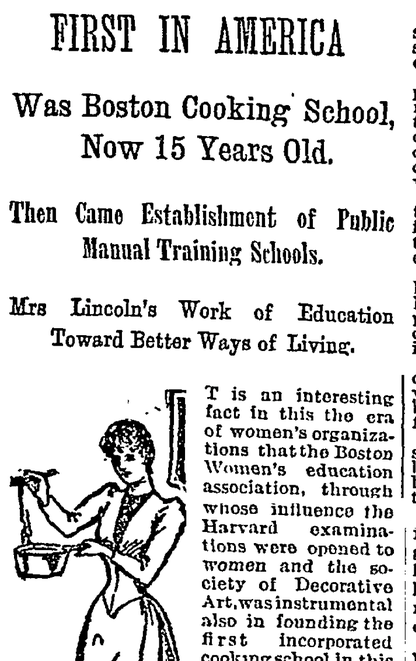

Image: “First in America was Boston Cooking School, Now 15 Years Old,” The Boston Globe, April 1, 1894.

“How did these women, generally viewed as maintaining a class and racial status quo, make their advice so appealing, so convincing, so natural, that women and men alike supported their depiction of domestic authority?”

Sarah Walden, Tasteful Domesticity, 3.

1880s: Changing Assumptions of Knowledge

Into the 1880s, the “proportional increase in the number of household servants” was larger than at any other point in U.S. History, but “demand far outstripped supply.”9 Working-class women, the original target of cooking schools meant to prepare them to work as domestic servants, instead found industry jobs in the growing urban centers. The end result was a much higher enrollment of middle and upper-class women seeking instruction to match the changing standards within the home. There was, in fact, “widespread concern” about the status of home cooking as an integral part of the emerging middle class; did these women actually know how to cook? The vague narrative of recipes of earlier generations was no longer up to par; it was now necessary to specify ingredients and instructions to assist the “middle-class kitchen novices” who were required to uphold new social ideals.10

Image: Gold Medal Flour advertisement, The Ladies’ Home Journal, (June 1907), 43.

26 April 1882

Irene Jones, my great-great-great-grandmother, marries Richard Davenport Gilliam, my great-great-great-grandfather.

7 September 1887

Eulalie Thornburg, my great-great-grandmother, is born.

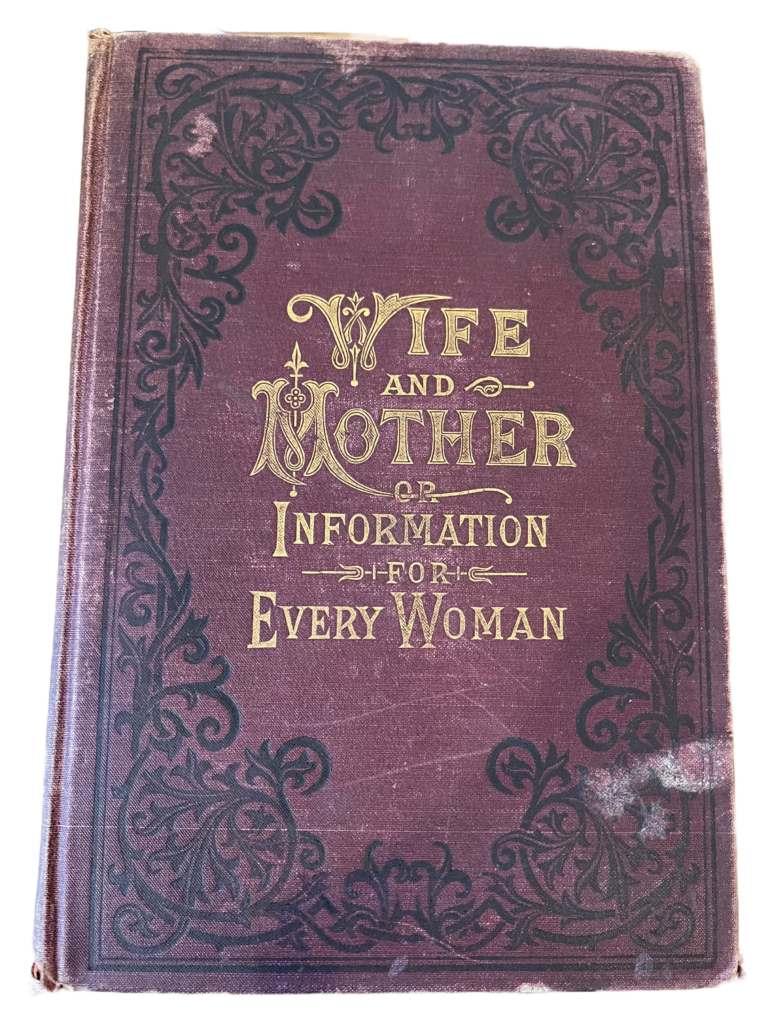

1888: Wife and Mother, or, Information for Every Woman

In its thirtieth edition, Wife and Mother was “adapted from the writings of Pye Henry Chavasse,” a “Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons,” and included an introduction by Sarah Hackett Stevenson, a “Professor of Obstetrics and late Professor of Physiology in the Women’s Medical College of Chicago.”11 The introduction lays out how “it is the duty of every one to know the laws of his own body, (…) but that does not imply the knowledge”; it is explicit that the authors will bestow this scientific knowledge on the poor women who do not know how to be a “good” wife and mother.12 Stevenson connects physical cleanliness to mental and moral sanity (“the temples of their [female patients] souls have probably never been cleansed”) and then to ignorance regarding healthy food habits, which is either “no work” or “all [the] work.” Idleness is just as harmful as overwork; the impossible balancing act of the duties of women in the home continued.13 She recommends to parents who are faced with “incurable” daughters to “discharge his cook and send [her] into the kitchen,” since the “gospel of work is full of cure for (…) invalid women.”14

1890s: The Progressive Era

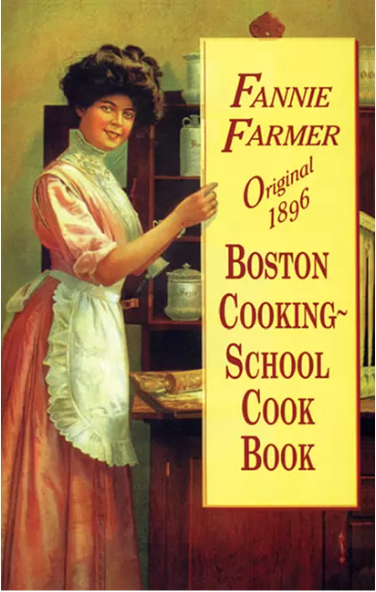

Combining “moral idealism” with new scientific and technological advances, the Progressive Era sought to “standardize” both home and work – effectively giving middle-class values and women’s domestic authority a “scientific backing.”15 The cookbook became a tool for public social reform and therefore needed to be revised to be available to the general public. Recipes now included a separate list of ingredients (previously integrated into the recipe narrative) as well as standardized measurements. The women of both the cooking school movement and the “home economics” movement “were in the business of creating knowledge and influencing taste.”16 Home economics had its foundation in the goal of “bettering the living of all people” and therefore promoted the kitchen as “the bedrock of the nation’s economy”; the nation’s cultural discourse and definition of taste were to be determined in the homes of middle-class women.17

Image: Cover of The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book18

1 November 1891

Emily Gordon Gilliam, my great-great-grandmother, is born.

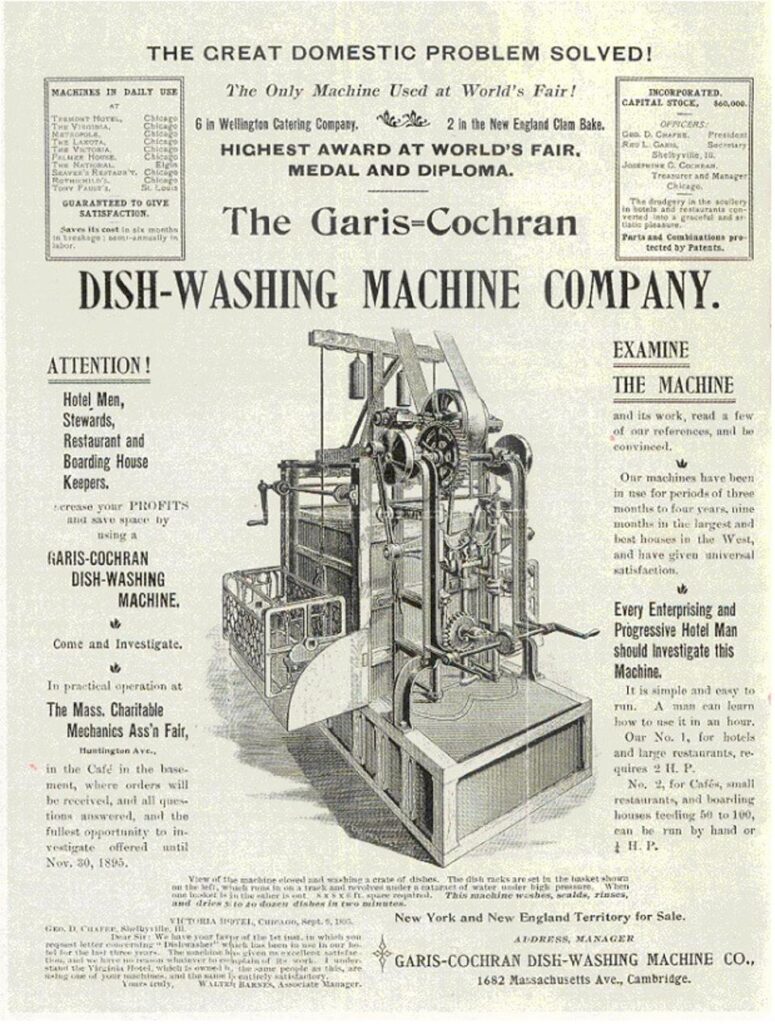

1893: Automation and Expectation

The arrival of automatic dishwashers as well as “the increased availability of processed and canned foods” further pushed domestic labor and its resulting food to become more standardized and “formulaic.”19 Limited due to cost, many new technologies only inhabited the homes of the elite, further shifting the ways in which domesticity was performed. The majority of physical domestic labor in middle and upper-class homes was performed by servants up until the end of the nineteenth century and they often prepared the steps within the cookbooks that touted the “moral value of the mother as a home manager.”20 The socially elite wife and mother, therefore, achieved her moral standing through the lack of physical labor that was a product of her tastes “informed by domestic literature.” Housework, and therefore the housewife, was rebranded in the name of science, combining “native intelligence, genuine familial love, and professional education” to attach professionalism to the “traditional associations” of the identity of wife and mother.21

Image: Advertisement for the “Garis-Cochran Dish-Washing Machine Company,” circa 1894. Public Domain.

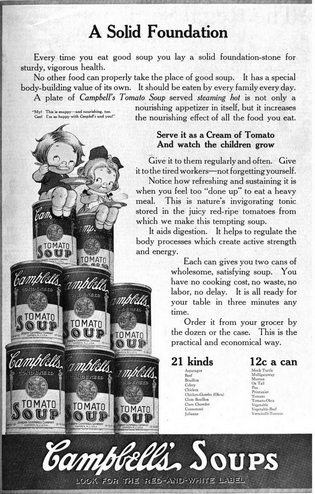

“Modernity’s blessings had limits, evidently, because the advertisements never once suggested that a man or child could heat up a can of soup. Advertisers tried to convince women that only they possessed the skill to cook in the modern world.”

Katharine Parkin, “Campbell’s Soup and the Long Shelf of Traditional Gender Roles,” in Kitchen Culture in America: Popular Representations of Food, Gender, and Race, ed. Sherrie A. Inness (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), 53.

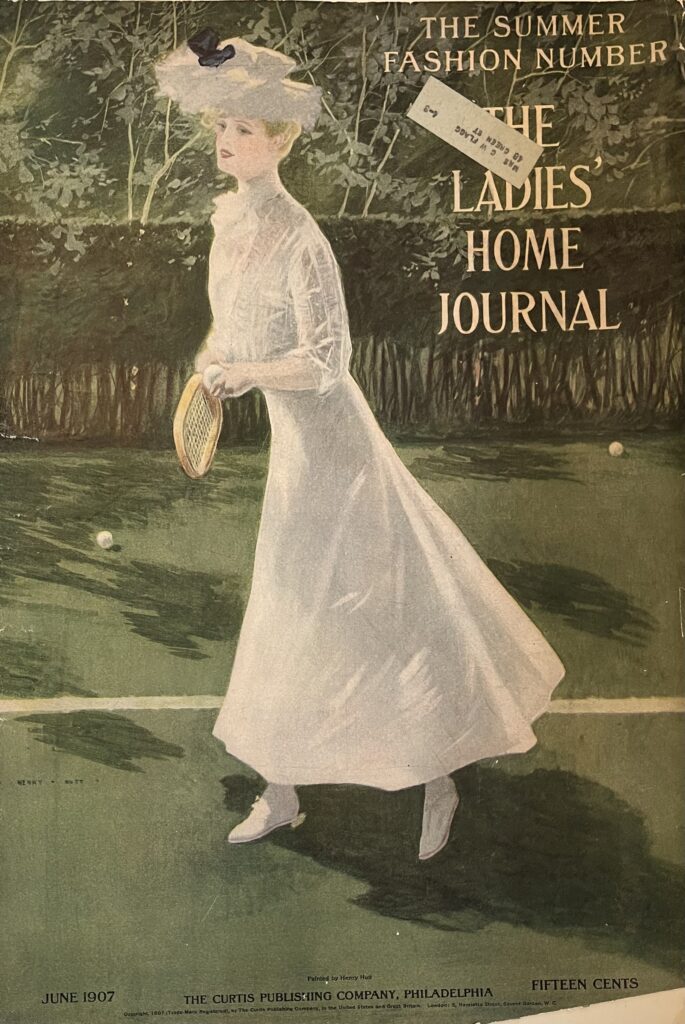

Early 1900s: Femininity in Food

The further removal of food from its “humble roots” allowed for a transformation within the home economics movement: food as a status symbol.22 “Progress” could only go so far in removing women from the kitchen; dainty food and fanciful dishes reassured American society that women were still ladies. Therefore, the standards for middle-class women and their relationship with food continued to expand in accordance with the availability of new technology; meals became increasingly elaborate and demanded purpose and preparation. If they were able to put the onus of washing dishes onto a servant or a machine, then they had time to “provide multicourse meals, dinner parties, hot lunches, (…) and tea parties.”23 Tea parties especially allowed the hostess to “display [her] feminine talents” and success as a housewife to peers of the same social class.24

Image: The Ladies’ Home Journal, (June 1907).

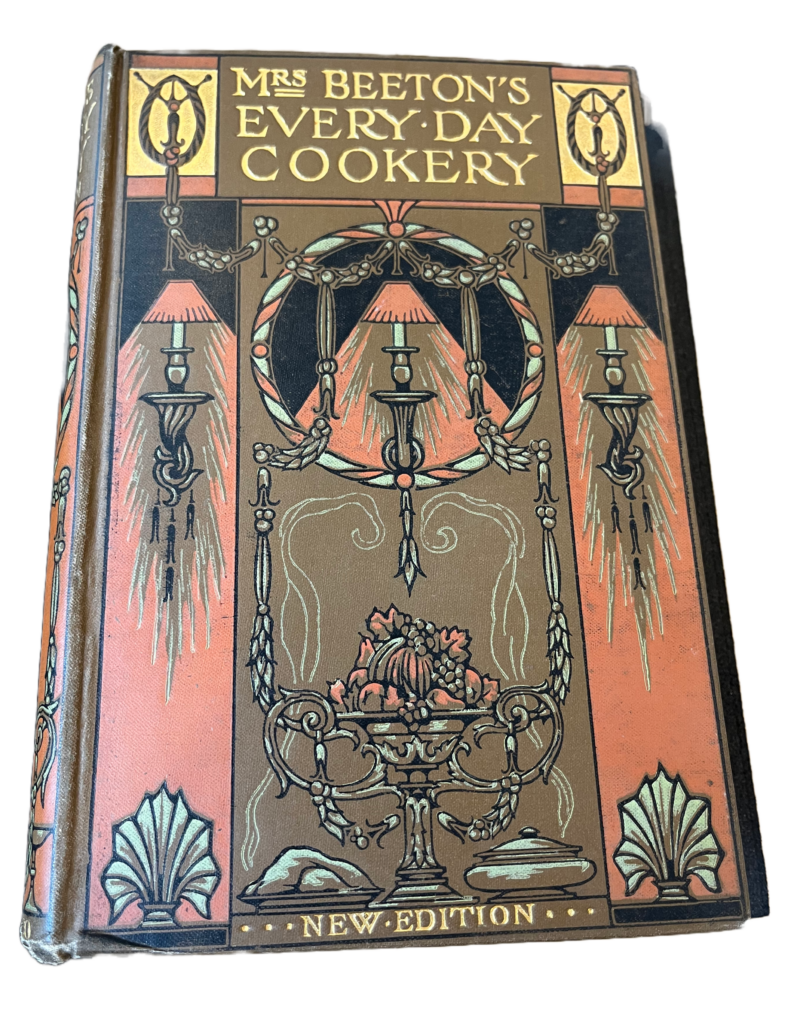

1907: Mrs. Beeton’s Every-Day Cookery

In stating the necessity for the book, the preface to Mrs. Beeton’s Every-Day Cookery mentions that “cookery schools and classes have (…) educated many mistresses to the possibilities of the art, and encouraged them to insist on more variety and delicacy in their daily fare.”25 There had been an expansion of tastes and awareness of cooking as more than a mother toiling in the kitchen, and Mrs. Beeton was there to provide a “comprehensive volume” to address these changes. Listed amongst the additions to this new issue are recipes “contributed by some of the most famous chefs and teachers of the art,” a reminder of the ancestral “practical knowledge” of carving, and “minute considerations” of the price of ingredients for “the housewife who gives the trouble [to know].”26 Cookery is further described as both an “art” and an “everyday science”; when listing the “reasons for cooking,” Mrs. Beeton specifically mentions “to combine the right foods in proper proportions for the needs of the body” (science) as well as “to make it agreeable to the palate and pleasing to the eye” (art).27 Food, far from being an endeavor for survival, had morphed into a scientific art meant to represent the best that modernity had to offer, and cookbooks, as well as home management literature, were the vehicles for its successful dissemination.

27 April 1911

Eulalie Thornburg, my great-great-grandmother, marries John Nathaniel Roper, my great-great-grandfather.

14 October 1914

Emily Gordon Gilliam, my great-great-grandmother, marries Jesse Hartwell Heath, my great-great-grandfather.

1915: Advertising “Smart, Strong, and Healthy”

The increased popularity and variety of periodicals that occurred in the first decade of the 1900s further responded to the heightened availability of branded, processed food by including advertisements alongside related articles. Cookbooks also adapted to these changes, including specifically named products or equipment, such as a Dover Egg Beater, as necessary for recipe success. Various kitchen appliances and equipment became more accessible to a greater number of consumers, including “toasters, chafing dishes, and waffle irons”; therefore, “the ties between domestic scientists and food, appliance, and utensil manufacturers” continued to strengthen.28 Companies like Campbell’s Soup specifically targeted young mothers and wives, “equating consumption of an article with social status and approval”; they appealed to the women’s sense of self as homemakers and accomplishment as mothers for their “desires for their children to be smart, strong, and healthy.”29 Leading into World War I, cookbooks increasingly paid more attention to nutrition, responding to the “pressing need to establish government standards for food production” and representing the advances in food science.30 The new message to housewives and homemakers? “Do Not Disappoint Your Own Children.”31

Image: Campbell’s Soups Advertisement, Woman’s Home Companion (1919). Public Domain.

13 February 1919

Sarah Fleming Heath, my great-grandmother, is born.

There is a need to address that “housewife,” as a term, was and is exclusionarily white. While white women were balancing the notion of conforming to new white middle-class ideals, the majority of African-American women were not included in any consideration of upward mobility, and in fact were often did the “basic” domestic labor for these white women. This dependence on the labor of others was, in fact, one of the factors that allowed white women to claim a higher class status. For generations, African-American women had been responsible for taking care of other people’s homes and other people’s children, and therefore, there are many culinary traditions that this country owes to them.

“Hired help” within middle and upper-class homes consisted of African-American women, working-class white women, and recent immigrants; the efforts to “standardize” food practices often directly correlated with “Americanizing” those who were under the employ of the upper classes and ensuring their conformity to the newly-established societal structures. The fact that the “American housewife” existed in this capacity in the post-Civil War era is precisely due to the exploitation and manipulation of non-white and non-socially-elite women. The related advances in domestic and food sciences were subsequently based on racist and classist foundations to “prove” how certain foods (and, therefore, the people who consumed them) might be superior as well as the want to improve white modernity. Unless otherwise stated, “middle class” refers to “white middle class,” as, during these periods, they were one and the same.

Further reading on this topic: Kitchen Culture in America: Popular Representations of Food, Gender, and Race (2001) and “Food and Nutrition through the 21st Century: Race, Class, Gender, and Food,” from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, accessed here: https://guides.lib.unc.edu/nutrition-history/race-class

- Jessamyn Neuhaus, Manly Meals: Cookbooks and Gender in Modern America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018), 17.

- Neuhaus, Manly Meals, 17.

- Neuhaus, Manly Meals, 17.

- Warshaw Collection of Business Americana: Food. Archives Center at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

- The American Housewife and Kitchen Directory, Preface.

- The American Housewife and Kitchen Directory, Preface.

- Neuhaus, Manly Meals, 18.

- Neuhaus, Manly Meals, 19.

- Neuhaus, Manly Meals, 19.

- Neuhaus, Manly Meals, 20-21.

- Pye Henry Chavasse, Wife and Mother, or, Information for Every Woman (Chicago: H. J. Smith & Co., 1888), i.

- Sarah Hackett Stevenson, Wife and Mother, iii.

- Sarah Hackett Stevenson, Wife and Mother, v.

- Sarah Hackett Stevenson, Wife and Mother, vi.

- Sarah Walden, Tasteful Domesticity: Women's Rhetoric and the American Cookbook, 1790-1940 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2018), 114.

- Walden, Tasteful Domesticity, 115.

- Walden, Tasteful Domesticity, 116.

- Fannie Merritt Farmer, "The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book." Mineola: Republication by Dover Publications, Inc., 1997.

- Walden, Tasteful Domesticity, 119.

- Walden, Tasteful Domesticity, 119.

- Walden, Tasteful Domesticity, 120.

- Sherrie A. Inness, Dinner Roles: American Women and Culinary Culture (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2001), 56.

- Neuhaus, Manly Meals, 19.

- Sherrie A. Inness, Dinner Roles, 58.

- Mrs. Beeton's Every-Day Cookery (London: Ward, Lock & Co., Limited, 1907), 6

- Mrs. Beetons, 6-7.

- Mrs. Beeton's, 17.

- Neuhaus, Manly Meals, 24

- Parkin, "Campbell's Soup and the Long Shelf of Traditional Gender Roles," in Kitchen Culture in America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), 53-54.

- Neuhaus, Manly Meals, 24.

- Parkin, "Campbell's Soup" in Kitchen Culture in America, 54.