“Urban renewal means Negro removal”

-James Baldwin, Interview on WNDT-TV, New York City, May 28, 1963.

The construction of the Central Freeway displaced thousands of Black San Franciscans. Tearing it down three decades later displaced many more. The role of city planning in enforcing stark inequalities is often glossed over, but the history of Hayes Valley offers a sharp illustration of these choices and impacts.

The 1940s saw a sharp climb in San Francisco’s Black population, growing almost ten times over from 4,846 in 1940 to 43,502 in 1950. The Western Addition, which includes Hayes Valley, went from 6% Black to 34% in that same time period, though these numbers are likely undercounts (Klein 13). As a bustling cultural hub, the Western Addition was known in the middle decades of the 20th century as the “Harlem of the West.” The district was also home to a large portion of the city’s Japanese Americans and immigrant communities.

As jobs and white residents fled cities nationwide post-WWII, San Francisco among them, tax revenue and blue collar jobs collapsed, resulting in high rates of poverty and unemployment. Due to practices of redlining and racist economic and social policies, residents of color were trapped in declining cities and bore the brunt of these hardships. In attempts to recover their depressed economies, cities took up the goal of modernizing and increasing their appeal via “urban renewal” (McDonald).

As a percentage of the city’s total population, San Francisco’s Black population was highest in 1970 at 13% (96,078 residents). This figure fell to 12% in 1980 and 11% in 1990. In 2000, this figure dropped to a mere 8% (Stewart). The city’s targeted urban renewal projects, which they also referred to as “slum clearance,” caused displacement within San Francisco beginning in the 1950s, which over time turned into people being pushed out of the city altogether. This was precisely the point of urban renewal: “As part of their case for action, the [city planners in 1966] point out that, based on population trends, by 1978 African Americans would make up 16.5 percent of the population, while a more desirable ‘target’ amount would be 13 percent (for whites, the trend was 71 percent and the target was 76)” (Klein 5-6).

As the number of people commuting into San Francisco skyrocketed in the 1950s, the city saw increased traffic congestion and responded with new infrastructure. City planners identified the predominantly Black Western Addition as a prime location for slum clearance and freeway construction. The construction of the Central Freeway in 1959 was one such urban renewal project. While San Francisco city planners characterized urban renewal plans as anti-poverty programs, this rhetoric fell short when they set out to relocate and hide poverty rather than eradicate it (Klein 8). As San Francisco’s legacy of urban renewal shows, the primary goal was to attract wealthy residents to the city at the expense of poorer ones, particularly poorer residents of color.

“One of the purposes of renewal when it was called slum clearance was not only to get rid of the people and the structures but to make sure those blighting influences didn’t come back. And so there was no intent to rebuild for the kind of people who were being displaced.”

-Gene Suttle, Former San Francisco Redevelopment Agency Deputy Executive Director and Western Addition Area Director

After damage in the 1989 earthquake and a sustained lobbying campaign by a group of neighborhood residents and business owners, the stretch of the Central Freeway north of Fell Street was demolished in 1991. In the freeway’s place came an influx of money, attention, development, and new residents and businesses, changing the makeup over the following decades so drastically that photos of the neighborhood in 1991 are almost unrecognizable next to today’s landscape. While some of these changes began to take shape in the years prior to the demolition with a handful of primarily art and design oriented shops moving in, the pace of change accelerated rapidly after the removal of the freeway.

Before the Central Freeway was ever built, city planners had chosen their targets

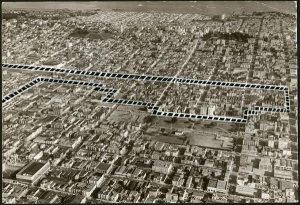

In 1947, city planner Mel Scott was hired by San Francisco to write a report on potential redevelopment of the Western Addition. This report highlighted the area’s high crime rates and unemployment as well as the condition of its housing as evidence of “blight,” which qualified it for “a clean sweep,” in Scott’s words (Klein 14). As part of this plan, Scott predicted a minority of the neighborhood’s current residents would be able to afford to remain there after redevelopment (Klein 16). The map above displays an area of the Western Addition that the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency selected in 1954 for the first of two phases of slum clearance in the district.

Does this shot remind you of any other maps you have seen? What are the complexities that come with drawing lines through communities?

1991 marked the highly anticipated demolition of a portion of the Central Freeway. At the start of 1992, City Hall Market, pictured here on the right, became Anna’s Market. New building projects sprung up in place of the freeway rubble and business began to boom in the neighborhood for the first time in decades. This boom was not felt positively by all Hayes Valley residents and business owners however, as many could not afford the rising rents in the following years and were forced to move or shut down.

What emotions do you feel when you look at this photo of the demolition next to the photo of the intact offramp? How might the day this second photo was taken have felt for residents of Hayes Valley or for the owner of City Hall Market?

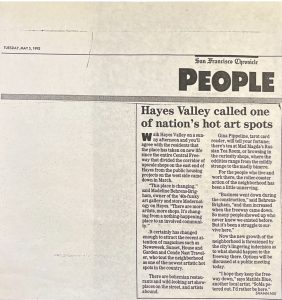

This clipping from the San Francisco Chronicle written by Shann Nix highlights the excitement of Hayes Valley merchants over the demolition of the Central Freeway section. Madeline Behrens-Brigham, a shop owner, declares that Hayes Valley “is changing from a nothing-happening place to an involved community.” Nix provides the reader with a sense of the neighborhood as a vibrant center of art. This piece appears to aim to inspire excitement in Chronicle readers about the changes afoot in Hayes Valley.

What other reactions may have existed alongside the ones that appear in this article? Why might alternate perspectives be left out here? Does this article feel similar or different from journalism you have read about neighborhood change today?

The above image is a Google StreetView photo from May of 2021 of the same spot as the previous photo of 1991’s freeway demolition, thirty years later. The same building remains at 424 Hayes St, though the paint is now forest green. In this photo, the storefront is for lease after Alternative Apparel closed, though their name is still seen here in the window. There have been at least three businesses at this address since the closure of City Hall Market, according to records from San Francisco’s Registered Business Locations open data set (https://data.sfgov.org/Economy-and-Community/Registered-Business-Locations-San-Francisco/g8m3-pdis/data).

What aspects of the past are visible in this photo? Walking down this block, what assumptions would you make about the neighborhood and its history?

With soaring levels of development and displacement in the section of the Western Addition now called Hayes Valley, the project of urban renewal appears to continue to this day, despite city officials condemning its damaging legacy.

Sources for Further Research:

San Francisco Public Library Digital Collections: https://digitalsf.org

“Western Addition: A Basic History” by Gary Kamiya https://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=Western_Addition:_A_Basic_History

“The Birth and Life of the Freeway in Hayes Valley” by Reginald McDonald https://hoodline.com/2015/08/hayes-valley-the-central-freeway/

Annotated Sources:

Klein, Jordan. “A Community Lost: Urban Renewal and Displacement in San Francisco’s Western Addition District,” 2008.

Relevance: Klein provides an in depth history of the Western Addition district and of urban renewal projects there. He also examines the history of urban renewal on the national scale, connecting local projects to national policy. Maintaining a city planning focus, Klein spends the second half of his thesis discussing attempts by the city to right the wrongs of urban renewal.

Schafran, Alex. The Road to Resegregation: Northern California and the Failure of Politics. University of California Press, 2019.

Relevance: Schafran thoroughly delves into multiple factors that have driven the relatively recent “resegregation” of the Bay Area. Of the sources on this list, Schafran’s book includes the largest focus on NIMBYism, which is essential in understanding San Francisco’s current housing affordability crisis. Mixing history and policy suggestions, Schafran both deepens and expands the scholarly and local conversations around gentrification, housing justice, and the racialized impacts of Northern California’s urban planning choices.

Shaw, Randy. Generation Priced Out: Who Gets to Live in the New Urban America. 1st ed., University of California Press, 2018, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctv5cgbsh.

Relevance: This book contains multiple chapters about gentrification in San Francisco and the Bay Area more broadly. Shaw provides a comprehensive overview of the forces behind the present state of displacement in various cities around the country. He focuses on various forms of resistance to gentrification and possible interventions that can be made by cities, illustrating that displacement is not an inevitability.

Bibliography:

Klein, Jordan. “A Community Lost: Urban Renewal and Displacement in San Francisco’s Western Addition District,” 2008.

McDonald, Reginald. “The Birth and Life of the Freeway in Hayes Valley.” Hoodline, October 23, 2020. https://hoodline.com/2015/08/hayes-valley-the-central-freeway/.

Schafran, Alex. The Road to Resegregation: Northern California and the Failure of Politics. University of California Press, 2019.

Shaw, Randy. Generation Priced Out: Who Gets to Live in the New Urban America. 1st ed., University of California Press, 2018, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctv5cgbsh.

Stewart, Juell. “San Francisco African American Reparations Advisory Committee Presentation.” San Francisco: Hayes Valley Neighborhood Association, September 2021.