Who cleans your house? Maybe you do, maybe the people you live with—your roommates, your family. If you live in a Smith College house, it is almost certainly a Smith college housekeeper, a member of the Local 211 housekeeping and dining workers’ union, who is part of a long line of (mostly women) workers that stretches back to 1895. Imagine your Smith housekeeper. What are they wearing? Does it look comfortable? Does it have pockets? Does it bear a Smith College logo on it? Where did these clothes come from? To understand how housekeepers’ uniforms have developed over time, it is necessary to understand how the jobs of Smith housekeepers have changed.

The earliest housekeepers were heads of houses, or house mothers. They were well-educated and respectable women who were tasked not only with cooking and cleaning for Smith students, but also providing them with academic and moral counsel. These women were not assigned a uniform, but instead dressed just as fashionably as their charges. They would also have donned aprons for cleaning, which they provided themselves. Because heads of houses were respectable women, they were not required to do the most arduous of tasks. There were laundresses, cooks, maids who assisted in the dining room and maids who cleaned the house, and many other people who made day-to-day operations possible.

What aspects of this Smith laundress’ clothing might set her apart from the students, faculty, or other staff?

The role of the head of house in Smith campus life remained strong throughout the first half of the 20th century, but as the campus grew they began to share more and more their duties with cooks and maids. Maids, like heads of houses, were integral parts of Smith students’ daily lives. They knew what food each student enjoyed, asked after the young women’s boyfriends, and developed friendships with the students. Not all students were close to the maids, one recalls barely noticing their presence even though they lived on the same floor in Chapin House. In 1941, the student publication The Tattler published an article titled “Maids We Have Known and Loved,” complaining that all the best maids would be drawn away to work in the war effort, and their replacements would be second-rate. Though students claimed the article was satirical, it caused a firestorm both on and off campus, with many people citing it as evidence that Smith students had a dismissive and snobbish view of their maids.

What does this cartoon imply about maids’ demeanors and their relationships with the students? How would the cartoon be different if the maid was depicted in the type of apron depicted in the photo?

Like many women spurred by their increased presence in the workforce during World War II, the all-female staff of Smith housekeepers unionized in 1941. Local 211, the housekeeping and dining workers’ union, negotiated with Smith administrators for better hours, better pay, more benefits, and more transparency. However, there was still a lot of fluidity in the job. Workers shifted between housekeeping and dining, often working under multiple supervisors. The job of a housekeeper was not very standardized at this time, as is evidenced from the fact that each woman in this photo wears a different uniform. They were likely given guidelines and instructed to buy their own garments to fit those specifics.

What are the elements that differ in each maid’s uniform? What elements are the same? From these comparisons, can you guess what the uniform requirements may have been?

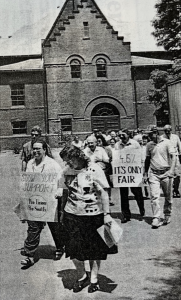

In 1972, the job of head of house was transformed into head resident and the housekeeping and dining staff were restructured, giving rise to the job of Smith housekeeper as it is known today. Local 211 was active in redefining the role housekeepers and continues to hold Smith accountable for fair treatment today.

Examine the slogans on the signs (SHOW YOUR SUPPORT Pro Union Pro Smith; 4.6% IT’S ONLY FAIR). What could these slogans refer to? What do they imply about housekeepers’ place in the Smith community?

Uniforms are a method of control. They transform individual workers into an identically-clad mass. However, uniforms also create solidarity. They help workers recognize each other as members of the same group, and in the case of current Smith housekeepers, provide opportunities to organize. In fall 2021, Smith housekeepers learned that instead of buying their own uniforms to meet a certain standard and being reimbursed (like the housekeepers in the photo from 1973), they were newly required to purchase uniforms provided by a specific company. The uniforms offered were ill-fitting and did not offer large enough sizes. Housekeepers felt humiliated and disrespected at the prospect of not being able to dress with dignity to perform their jobs. The issue is ongoing, but it has brought members of the housekeeping staff together, as well as students who have allied themselves with their cause.

For further research:

Patel, Mikayla, “‘We get treated like crap’; Housekeepers React to Change in Policy Under New Management.” The Sophian, 13 December, 2021. https://thesophian.com/we-get-treated-like-crap-housekeepers-react-to-change-in-policy-under-new-management/

Smith College Archives, Buildings and Grounds Files. https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/4/archival_objects/170468

Smith College Historic Clothing Collection on Jstor. https://www.jstor.org/site/smith/historic-dress/

Annotated Sources:

Crain, Marion, “Feminizing Unions: Challenging the Gendered Structure of Wage Labor,” Michigan Law Review, Vol 89, No. 5, March 1991.

This article situates Local 211 in the broader history of unions, especially because Smith’s housekeepers have been primarily women throughout history.

Godson, Lisa & Tynan, Jane &, Uniform: Clothing and Discipline in the Modern World (Bloomsbury, 2019)

This book examines all sorts of uniforms, from schools to religious institutions to workplaces. It provides an overview of both different types of uniforms and theoretical thinking about uniforms. It is the most contemporary of these texts, so it will give me the best sense of where scholarship on this topic is today.

Gutiérrez Rodríguez, Encarnación, Migration, domestic work and affect: a decolonial approach on value and the feminization of labor (Routledge 2010)

This book will help me situate my research in the broader context of the issues faced by domestic workers, as many Smith housekeepers throughout history have been immigrants from countries such as Ireland and Poland.