INTRODUCTION

W. E. B. Du Bois’s legacy touches nearly everything, but he is almost never explicitly recognized. His 95 years of scholarship and activism between 1868 and 1963 continue to inspire those who engage with his ideas. Du Bois’s body of work includes fiction and nonfiction, articles, essays, speeches, and books. Readers today are still guided by his ideas of “double consciousness” and the “talented tenth,” and insights about race, economics, diaspora, democracy, history, and sociology, even though some of these ideas are now over a hundred years old. (“Du Bois Papers”)

In addition to his published writing, he also wrote letters. Dr. Du Bois amassed a huge archive which is now located at the UMass Amherst Library named for him. For this project, I’ve selected just 15 letters written by Du Bois from the collection of 8,086 pieces of correspondence UMass has digitized. These 15 letters are paired with the fifteen Sorrow Songs that Du Bois chose to begin each chapter of The Souls of Black Folk (1903). The content of each letter relates to the lyrics of the song.

Three categories organize the letters in my project: those written as a family member, as a friend, and as a professional. I’ve chosen one letter from each of these categories to share here.

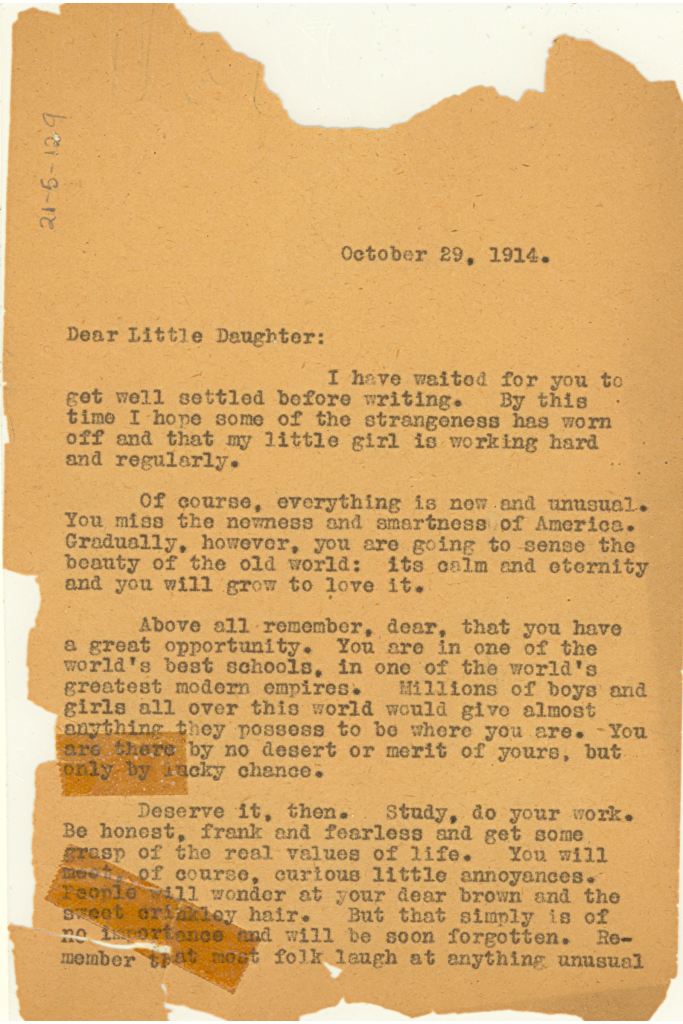

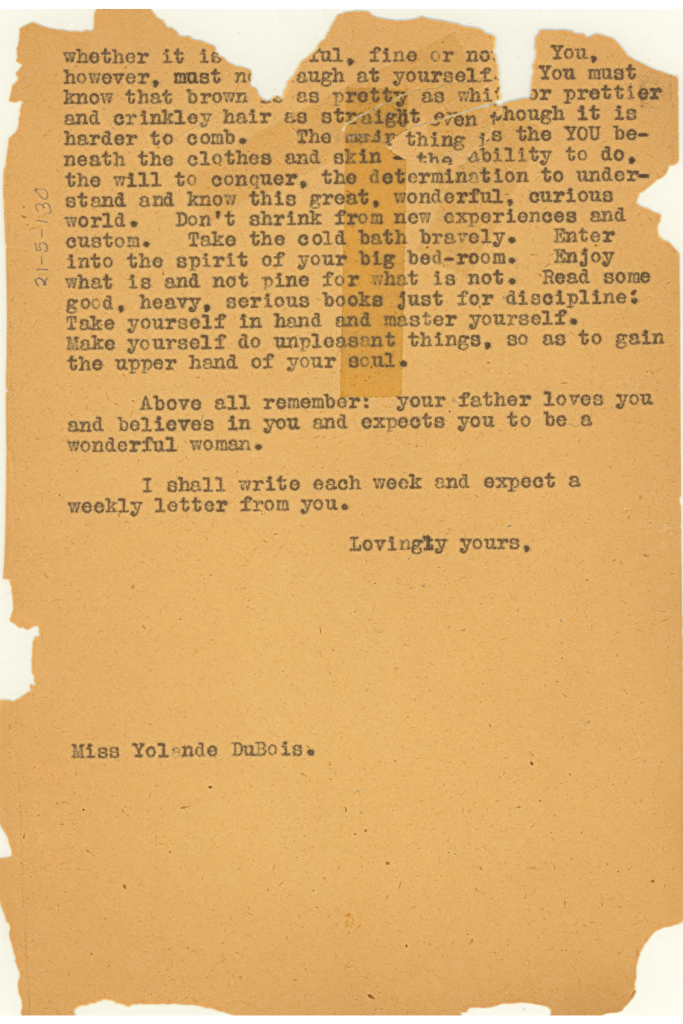

Family: To his daughter Yolande Nina Du Bois

Du Bois wrote this letter to his thirteen-year-old daughter Yolande while she was in Europe during World War I. Yolande had started at the Bedales School, an experimental boarding school that was the first in the United Kingdom to become co-ed. (Lewis 2009, 297) Even before Yolande went to study abroad, Du Bois was often absent during Yolande’s childhood while working away from home. (Lewis 2009, 289) So letters like these to his “Dear Little Daughter,” were all the more meaningful.

I’ve paired Yolande’s letter with the song “Bright Sparkles in the Churchyard.”

Oh, mother, don’t you love your darling child,

Oh, rock me in the cra-dle all the day. (Sundquist 1993, 508-09)

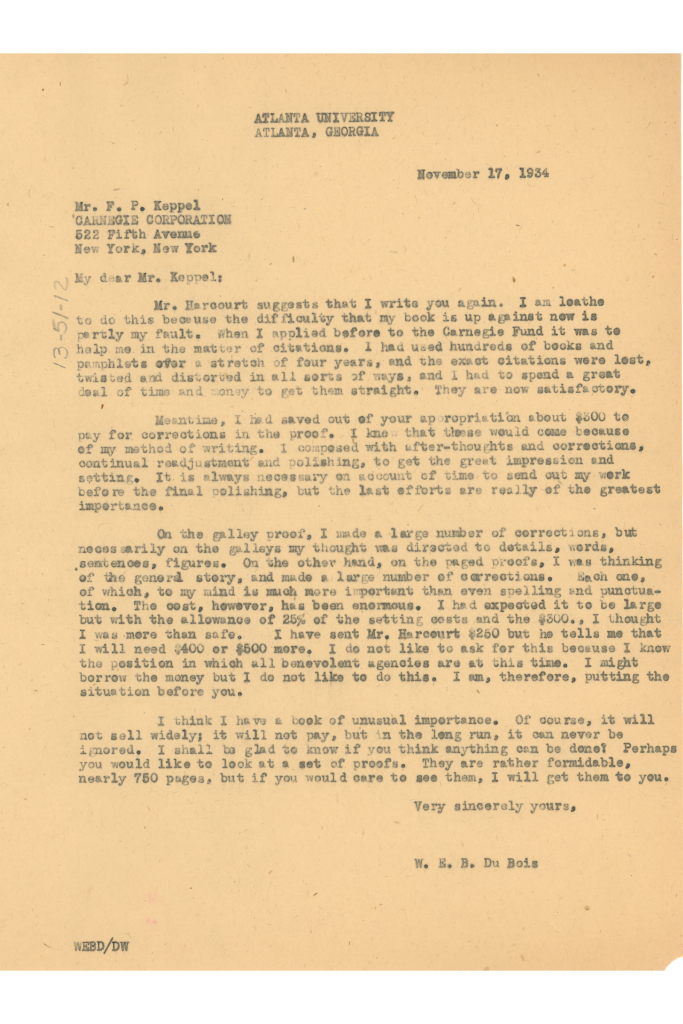

Professional: To F. P. Keppel of the Carnegie Corporation

This letter concerns Du Bois’s nearly 800-page book, Black Reconstruction in America, which was published a year later in 1935. (“Du Bois Papers”) He is asking the Carnegie Corporation for “$400 or $500 more” to finish editing. The request reveals some about how Du Bois conducted research. He tells Keppel that he previously applied for funding to help with citations which included “hundreds of books and pamphlets over a stretch of four years, and the exact citations were lost.” Why go through all this headache? Du Bois thinks he has “a book of unusual importance.”

I have paired this letter to Keppel with the song “I’m a Rolling.”

Won’t you help me in the service of the Lord? (Sundquist 1993, 505)

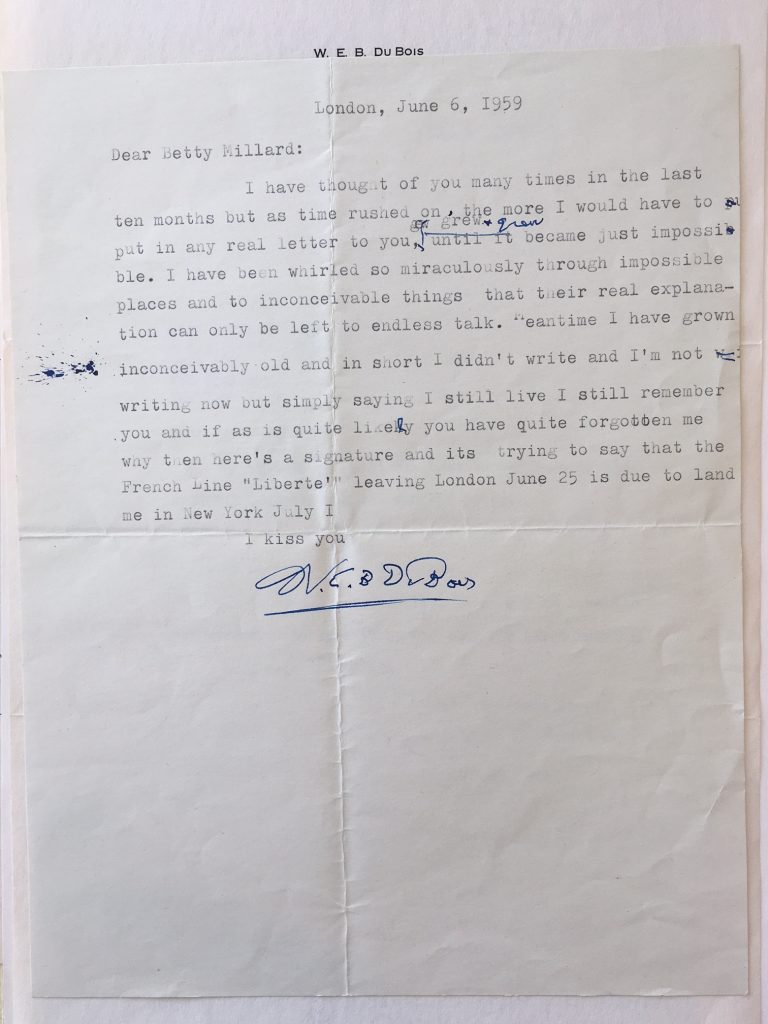

Friend: To Betty Millard

At the end of his life, Du Bois, at 91 years old, wrote this letter to Betty Millard. Millard was in the next generation of activists, 43 years younger than Du Bois. Among their common interests was Communism. Millard joined the Communist party in 1940 but then left it in the early 1950s. (“Millard Papers”) Du Bois started engaging with Marxism in his writing in the 1930s, (“Du Bois Papers”) but did not apply for membership to the US Communist party until the very end of his life in 1961, two years after this letter. (Lewis 2009, 709) Both Du Bois and Millard were investigated by the American government during the 1950s. (“Du Bois Papers,” “Millard Papers”)

This letter serves as a marker of Du Bois’s evolution of thought over time. At the beginning of his career, he would not have had much of a reason to write such a loving letter to a former member of the Communist party.

I have paired Millard’s letter with “I’ll hear the Trumpet Sound.”

You may bury me in the East,

You may bury me in the West,

But I’ll hear that trumpet sound

In that morning. (Sundquist 1993, 522)

CONCLUSION

These letters, as much archival material does, shows the work that took place behind Du Bois’s public persona. Here we see Du Bois as a father, a husband, a friend, a grant applicant, and in private correspondence with the likes of Albert Einstein (Weinberg 2012, 6) and Zora Neale Hurston. (“Du Bois Papers”)

Compared with his published works, Du Bois’s letters present a more personal type of writing, foregrounding his humor and thoughtfulness. He puts a remarkable amount of care in composing a letter theoretically only one other person would read. These glimpses behind the curtain help us feel closer to understanding who he was as a person. As it is for everyone else, Du Bois’s identity and experiences affected how he interacted with and wrote about the world. Ultimately, these letters, which give us a better understanding of Du Bois, help us better understand the grand ideas that Du Bois shares in his public writing and trace their evolution over time.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- Is there a difference in the way Du Bois writes letters to his family, friends, and professionals? Did his writing style change over time?

- Why might the paper of the letter to Yolande look so much more beat up than the other letters?

- Do any ideas in these letters feel dated? What ideas, if any, feel modern?

ANNOTATED SECONDARY SOURCES

Itzigsohn, José and Karida L. Brown. The Sociology of W. E. B. Du Bois: Racialized Modernity and the Global Color Line. New York University Press, 2020.

Itzigsohn and Brown’s book provides insight into the main ideas in Du Bois’s writing, and how they apply to the present moment. It also discusses how Du Bois’s work has largely been left out of sociology classrooms. The authors make a case for why Du Bois should be taught much more widely.

Lewis, David Levering. W.E.B. Du Bois: a Biography. New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2009.

David Levering Lewis’s 2009 biography of Du Bois is an abridged version of his early 2000s two-volume biography of Du Bois. It holds a wealth of information on the life of Du Bois and his family. Lewis and his team won the Pulitzer Prize for the first edition of this book.

Weinberg, Meyer, ed. The World of W.E.B. Du Bois: A Quotation Sourcebook. Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012.

This collection of quotes serves as an approachable entry point for learning about Du Bois. In twenty themed chapters, it organizes short, punchy quotes from throughout his life from all forms of his writing, including his letters. Weinberg’s introduction echoes Itzigsohn and Brown’s, as he laments that the average college student in the US barely knows the name of Du Bois. He explains that that is a great loss and emphasizes Du Bois’s relevance.

FURTHER RESEARCH

I recommend exploring the completely digitized Du Bois Papers through the UMass Amherst Archives. It’s also more than worth the PVTA trip to the UMass Special Collections & University Archives to see some of the collection in person.

The Du Bois Center at UMass Amherst is another great resource for research help and Du Bois-related programming.

REFERENCE LIST

“Betty Millard Papers.” Smith College Libraries. https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/2/resources/1179.

Lewis, David Levering. 2009. W.E.B. Du Bois: a Biography. New York: Holt Paperbacks.

Sundquist, Eric J. 1993. To Wake the Nations: Race in the Making of American Literature. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

“W.E.B. Du Bois Papers: Collection Overview.” UMass Amherst Libraries, Special Collections and University Archives. http://findingaids.library.umass.edu/ead/mums312.

Weinberg, Meyer, ed. 2012. The World of W.E.B. Du Bois: A Quotation Sourcebook. Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press.