From its start in early 1973, Olivia Records sought to create change in the music industry and in the world. The early 1970s saw the emergence of the lesbian community in conjunction with the women’s movement as a newly visible political force, eager to make their voices heard and see themselves represented. Bringing together their varied backgrounds as activists, political theorists, and folk performers, a group of ten women formed Olivia Records as a lesbian feminist record label based in Washington, D.C. (Morris, Smithsonian). As one of the foremost women’s music record companies operating at the national level, Olivia created and distributed music for women–especially lesbian women–and by women. Their aim was twofold: to create music celebrating queer women, and to create opportunities for women‘s employment.

Olivia Records was a key part of the emerging genre of what would come to be called women’s music, music that centered women and women’s experiences. As a genre, women’s music drew lessons from the civil rights movement and the significance of Black freedom songs and protest music to the movement (Morris, Disappearing L 25-26). In the coalescing efforts of the Olivia founders in the early 1970s, music that spoke to women’s experiences and realities was a natural point of intersection between the lesbian feminist activism of women like Ginny Berson and the musical artistry of Meg Christian–both key figures in establishing Olivia (Berson 59). Through the powerful medium of song, the women of Olivia built up a national network of communities of women united in celebrating and supporting women.

In a recent memoir of the Olivia Records years, Ginny Berson described how she saw the Olivia vision in the broader workings of the women’s movement:

“…there was a part of the women’s movement of the 1970s that was visionary, revolutionary, anti-racist, and very grounded in women’s real needs and aspirations. We understood that culture and politics were not separate, that each was informed by the other and, when consciously united, created a much more powerful force for change. We were going for hearts and minds. We did not want a piece of the ‘the pie,’ which we considered poisoned, contaminated by greed and the need to dominate. We wanted a whole new pie, filled with love and justice and with enough for everybody,” (Berson 15).

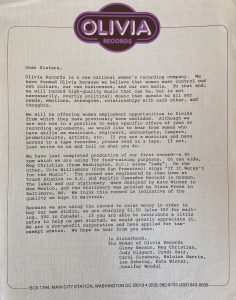

In an era before the internet, reaching people and getting the word out about small companies like Olivia Records was much more challenging. This letter introducing Olivia Records was sent to the mailing list the Olivia women were compiling, a list of all the women they could think of who might be supportive, willing to donate some funds, and whose addresses they had (Berson 82). With this letter, the founding Olivia women laid out a brief statement of their mission and the kind of skilled women they were looking to bring in. The first record produced by Olivia, a 45 rpm (a single), had Meg Christian’s version of Carole King’s “Lady” on one side, and Cris Williamson, a folk singer from California, singing her own song, “If It Weren’t for the Music,” on the other–performances that both women donated. The 45 was intended to be used as a fundraiser, a sample of the Olivia vision that would be sent out to women in the music industry who might be interested, but ultimately to meet their financial goals the Olivia women turned to selling the record to the public (Berson 78, 87).

The women behind Olivia were essentially starting from ground zero. With little to no starting funds or knowledge of how to run a record company, they took classes on recording engineering and taught themselves how to produce records and concerts, how to distribute albums and handle sales, all with the goal of taking control of all aspects of record production and setting their own terms in a notoriously paternalistic industry, (Berson 89; Morris, Smithsonian). In this September 1974 letter from Ginny Berson to Cris Williamson, Berson gives the costs and sales figures of the 45 rpm, bookkeeping that she learned how to do and keep track of herself. Having been released in May 1974, by September 6 they had sold 828 records, earning a total of $1056.45–a few hundred shy of their total expenses for the record ($1442.93).

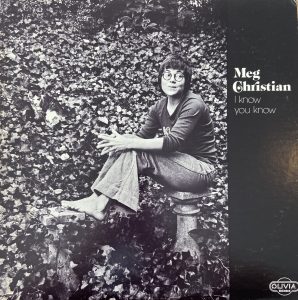

The first full-length record Olivia produced was Meg Christian’s album, I Know You Know. The photograph on the album cover above was shot by Joan E. Biren, or JEB, a feminist photographer whose work centrally documented queer life (Berson 106). Released in 1974, the album included both touching and humorous songs about lesbian life, including “Valentine Song” and “Ode to a Gym Teacher,” and was one of the earliest albums celebrating lesbian identity (Morris and Withers, 108). I Know You Know was a resounding success for Olivia, selling thousands of copies in its first year and proving that there was an audience and an appetite for this music.

Questions:

- Does the language of the first letter suggest any specific targeted audience or demographic? Who might the women of Olivia have been envisioning when writing this letter?

- What would it have meant for women in this time period to have control over and the ability to learn the skills for all the varying aspects of record production?

- What role does music play in social movements? Can you think of other contexts/examples in which music or song has been integral to movements for change?

Secondary sources:

Lula, Chloé. “12 Essential Songs From the Lesbian Label Olivia Records.” The New York Times. June, 23, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/23/arts/music/olivia-records-lesbian-playlist.html

Through a selection of songs from Olivia-produced albums, Lula highlights the diverse sounds and stories of Olivia Records and the impact many of these songs had on their audiences.

Morris, Bonnie J. and D-M Withers. The Feminist Revolution: The Struggle for Women’s Liberation. London: Elephant Publishing Company Limited, 2018.

The Feminist Revolution is a broader study of late-twenthieth century women’s rights campaigns, and gives helpful contextualization of lesbian feminism and culture in the wider span of the women’s liberation movement.

Morris, Bonnie J. “How Should We Archive the Soundtrack to 1970s Feminism?” Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Magazine, March 30, 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/how-should-we-archive-soundtrack-1970s-feminism-180968637/

In this Smithsonian Magazine piece, Morris thinks about the legacy of Olivia Records–how the record label should be remembered, collected, and exhibited–and about the urgency of preserving these stories while much of the original community is still alive.

For further research:

Matthews, Crys. “Love In Abundance: A Guide to Women’s Music.” NPR. June 17, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/06/17/877383217/love-in-abundance-a-guide-to-womens-music

“Women’s Music Index.” Queer Music Heritage. http://www.queermusicheritage.com/women.html?fbclid=IwAR2DWC7SRRVijKX30uU_QIQ1C7GzjpYmynUJ1ZuYgKURm7FFqTvgVp-yuvQ

Smith College Archives, Ginny Berson papers. https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/2/resources/1659

Smith College Archives, Women’s Music Archives records and collected music. https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/2/resources/891

Bibliography

Morris, Bonnie J., “How Should We Archive the Soundtrack to 1970s Feminism?” Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Magazine, March 30, 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/how-should-we-archive-soundtrack-1970s-feminism-180968637/

Morris, Bonnie J. The Disappearing L: Erasure of Lesbian Spaces and Culture. Albany: Suny Press, 2016.

Berson, Ginny Z. Olivia on the Record: A Radical Experiment in Women’s Music. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 2020.

Morris, Bonnie J. and D-M Withers. The Feminist Revolution: The Struggle for Women’s Liberation. London: Elephant Publishing Company Limited, 2018.