Humans flow through the criminal justice system everyday — what about humanity?

When Lynne Sullivan was a young girl, she “wanted to be everything.” An archeologist, a chef, a lawyer. The exact “everything” has shifted with time, but the ambition remains. Sullivan has finished cosmetology school and worked as a hairdresser, trained and served as a paralegal, has a drug and alcohol counseling license, and earned a Master’s degree in Criminal Justice from Boston University.

Before all this, she also had a decade-and-a-half long tenure in prison. In 1999, Lynne Sullivan was found guilty of second-degree murder after fatally stabbing her friend. She was admitted to the Massachusetts Correctional Institution (MCI) in Framingham and set to serve a life sentence.

At the beginning of her sentence, Sullivan had trouble adjusting. “Let’s just say the first five years was a lot of going back and forth to solitary confinement and trying to integrate into a society that I really didn’t know.”

Each time she finished a stint in solitary, her friend, who she nicknamed “Wiggles,” would be waiting for her. And each time, Wiggles would ask her if she was ready to go back to school.

Eventually, she was. Sullivan worked for and received her GED, and with mentorship from the Partakers Program — a nonprofit working on providing mentorship to people who are incarcerated — she took courses from Bunker Hill Community College, whose credits made her eligible to enter the Boston University Prison Education Program.

Wiggles, Sullivan described, “always had this contentment,” and Sullivan soon learned why. Education helped Sullivan and her fellow classmates develop a renewed identity.

“When you’re incarcerated and you go to school, you’re a student,” Sullivan explained. “Even if you’re in gangs or you have issues with certain people, when you’re in that classroom, you’re just a student. You’re not my enemy. You’re not that one I don’t like. All that gets put to the side, and our professors and teachers that come in treat us like human beings.”

Compassion and resources helped Sullivan change the trajectory of her path. She took on a guiding role for newcomers and would try to set them straight, whether through the “Listen, Learn, Change” program she launched or with a guard-sanctioned smack upside the head. Now, 24 years later, she has since been paroled. She recently purchased her first home, where she lives with her dog and two cats, and for the past six years, she has been a regional manager for the Petey Greene Program, a nonprofit that provides tutoring services to incarcerated people.

“And right now, this is what I love to do,” she said. “I get to inform people on the outside about the fact that you have human beings on the inside, against what everything society says. They’re not the number that you put on. They’re not the crime that you are labeling them with. They’re human beings that are behind that wall.”

THE PROBLEM, QUANTITATIVELY: TAKING STOCK

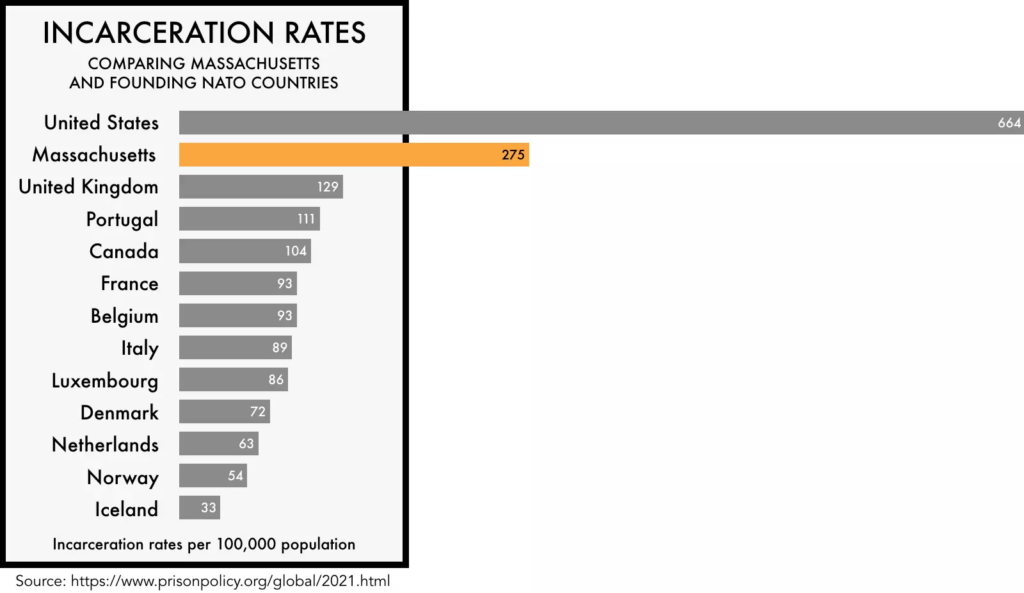

An analysis by the Prison Policy Initiative revealed that as of 2021, Massachusetts had the lowest incarceration rate of all of the United States at 275 incarcerated individuals per 100,000 people. But this rate, compared to other nations, would rank 17th in the world, higher than Iran, Colombia, and all the founding NATO nations.

Sheer volume isn’t the only concern. The criminal justice system imprisons Black and Latino people at rates 7.9 and 4.9 times higher than those of white people, according to a 2020 report from Harvard Law’s Criminal Justice Policy Program. In 2017, the Sentencing Project published a report highlighting central causes within the criminal justice system of these disparities. They named criminal justice policies that have disparate racial and economic impacts, implicit racial biases, and resource allocation decisions. These factors, the author notes, exist on top of “conditions of socioeconomic inequality [that] contribute to higher rates of certain violent and property crimes among people of color.” That is, the cards are stacked against people of color, and the criminal justice system compounds that fact.

“We have criminalized black and brown skin,” said Molly Ryan Strehorn, a defense attorney based in Northampton. She noted the difference in baseline levels of suspicion held by officers’ based on their perception of a person’s skin tone as well as the speed with which force escalates. “Police are able to [safely] arrest a white shooter who admitted to killing and shooting people. And at the same time, we have somebody [of color] who has a wallet or doesn’t want to get out of a car, and they lose their life.”

These numbers also don’t capture the full picture since the punitive system isn’t just contained within prisons and jails. “We also have a nation of supervision,” Ryan Strehorn noted.

And when somebody’s on probation, they kind of live in constant fear.

Molly Ryan Strehorn, attorney

A 2023 Prison Policy Initiative report states that there are 38,000 people in Massachusetts on probation: more than twice as many people as the number of people in local jails, state prisons, and federal prisons in Massachusetts combined.

“And when somebody’s on probation, they kind of live in constant fear,” Ryan Strehorn explained. If on probation due to substance-related offenses, “You have to wake up and call a phone number to find out if you’re going to need to get [drug] tested that day. And you do this every day. So how do you have a job? How do you be reliable for your family? How do you attend other social functions when you have to, in the middle of the day, go and provide a urine sample?”

From what Ryan Strehorn has seen, despite changing narratives around criminal justice, the enforcement of “tough on crime” sentiments are still pervasive. Ryan Strehorn says that if a person fails a drug test, “It’s not like, ‘It was to be expected because it’s a recurrence of a medical condition.’ It’s like, ‘They violate, and they’re criminalized, and let’s lock them up.’”

…AND QUALITATIVELY: WALLS TALKING

“You’re being screamed at by staff,” Sullivan described. “You have a window that a male officer can look in while you’re using the bathroom or changing your clothes.” She noted officers “walking through a shower stall while you’re taking a shower” and rooms getting torn up and personal items getting thrown away during searches. “So these are things that just re-traumatize on a daily basis, especially any woman that has been affected by any kind of abuse.”

In addition to daily occurrences like these, traumas from conditions like solitary confinement – which can also be a daily occurrence – have lasting effects.

Ellen Kaplan started experiencing serious health complications in her 40s. Eventually her mental health also suffered: “During one of my million operations and bed rests and inability to walk, I started getting so depressed. I think I was having a mastectomy and a hip replacement, one after the other. So I felt like I was the most depressed person in the world.”

Kaplan expressed these feelings to a friend who was working with the Innocence Project. “Well,” Kaplan recalls her friend responding, “I can introduce you to people who are more depressed than you.”

We take in what the world says about us. ‘I’m loathsome. I’m terrible. I cannot be with other human beings.’

Ellen Kaplan, Emerita Professor

Slowly, Kaplan began corresponding with several men on death row. Dr. Robert L. Cook, AKA “Cush,” had been on death row in Pennsylvania and spent 29 years in solitary confinement. He and Kaplan had become good friends, and he introduced her to different people to write to. And as she got to know these men, she developed an idea: to bring together their writings and put them into a play.

The work culminated in a piece called Someone is Sure to Come, which features writings from Cush, Jarvis Jay Masters, and other men on death row. It has since been published in Tacenda Literary Magazine and performed on-stage.

Kaplan wrestled with her own position in the writing process and how working with the people on death row affected her. “How could it not?” she asked. “And so there’s a character that evolved that is really the writer.”

The character is called Girl with Braid. “It’s me, and it’s a young girl. She’s seeing spots and hearing voices and getting panicked and thinking there’s somebody out there, she thinks she’s floating on an iceberg, and there’s somebody out there that’s going to come and save her.”

The character is experiencing sensory deprivation, which can contribute to psychosis and damage “brain structure and function,” according to an article in Scientific American. Kaplan spent three days in solitary when she was 16 years old and described it as a “horror”: on top of sensory deprivation and the claustrophobia, Kaplan noted, “We take in what the world says about us.” The walls told her, “I’m loathsome. I’m terrible. I cannot be with other human beings.”

Kaplan related this feeling to when she visited the Holocaust Museum in Washington D.C. for research. By the end of her visit, she said, “I had a fever. I was sick. It was so horrifying. There was no way around it. The very presence of those walls, the elevators like enclosed chutes.” At the core of it, she said, “We are — all of us — deeply affected by our history and our histories. And my history is with Jews, but not only with Jews: it’s with women, it’s with the world, it’s with anybody who hurts. And I am hurt about that. I mean, physically, really, we all are.”

…AND FISCALLY: FINANCIAL BURDENS

As a lifer, Lynne Sullivan always got the “best,” or highest paying, job at MCI-Framingham: cleaning in the Health Services Unit. That job earned her $14 per week.

Lifers receive their full paychecks, but for others, half of their income goes into savings where they can’t access it. “So that would mean that I would be living on seven dollars a week if I wasn’t a lifer. There’s not much you can buy for seven bucks.”

According to a report by the Lifer’s Group, a group of people serving life sentences at MCI-Norfolk, during the 2022 fiscal year, the Massachusetts Department of Corrections (DOC) spent an average of $127,736 per incarcerated person. (This number seems to be corroborated by a report by the DOC.) But when the government laments the cost of housing an incarcerated person, Lynne Sullivan laughs, “You forgot to add about how much you’re getting for us!”

Despite this cost per person, there’s a lot that incarcerated people need to buy. For example, hygiene products — “they give you this half a bar of soap and a little teeny bottle of shampoo,” Sullivan said, holding her fingers a couple inches apart — including menstruation supplies. “The most humiliating thing is when you’ve got to walk into an office where a 20 year old boy is sitting with a uniform on saying, ‘Hey, can I have a few pads?’ And he hands you two, and he thinks that’s good. They don’t get it, but it’s humiliating and embarrassing.”

Sullivan also described the need to purchase food to supplement limited portions, clothing to supplement poorly fitting and climate-inappropriate uniforms, electric fans and blankets to supplement building conditions, and communication with loved ones.

In addition to making their own wages, Sullivan describes family members who might have “a second job just so you can be halfway comfortable in a prison system that treats you like shame.”

However, the Massachusetts tides may be changing: in November, Governor Maura Healey signed a bill into law that makes phone calls free for incarcerated people. The law went into effect on December 1st, making Massachusetts the fifth state to provide such services.

Gov. Healey additionally approved a policy capping the inflation of commissary prices to three percent of purchase cost in the 2024 fiscal year budget.

Prisoners Legal Services Senior Attorney Bonita Tenneriello, quoted in the Boston Herald, noted that, nationally, prices can be inflated 20-50% nationally. Site commissions, she said, are “basically the consumer paying to subsidize the correctional agency.”

In addition to funding DOC programs, the work of incarcerated people raises profits for private corporations. “Prison labor is as close to slavery as we can get to under the 13th amendment,” wrote Terry-Ann Craigie, a labor economist and professor at Smith College. “Numerous corporations such as McDonalds, Walmart, and Victoria’s Secret, are able to boost profits simply by using prison labor, which has negligible wage costs.”

Craigie also compared carceral systems across similarly developed countries, stating that the United States’ system is “largely punitive with little investment in rehabilitation of people who are incarcerated. Without rehabilitation, former prisoners are left devoid of the skills they need to properly reintegrate into society, leading to a decline in the welfare of our society as a whole.”

In other words, the system “throws people away,” said Lynne Sullivan. “And we say they’re not safe for society, but, it’s not that they’re not safe for society. For the most part, society failed them, and you’re continuing to fail them by retraumatizing them on a daily basis instead of giving them the tools that they need to heal and then to grow and then to thrive.”

There’s no such thing as a ‘trauma-informed’ prison because prison is inherently traumatic.

Jo Comerford, MA Senator

In 2021, the Department of Corrections proposed new plans for a new “trauma-informed” women’s prison to replace the aging facility in Framingham. But a number of voices have pointed out a paradox here: “There’s no such thing as a ‘trauma-informed’ prison because prison is inherently traumatic.” State Senator Jo Comerford is among these voices.

“The insidious thing about prison construction,” Comerford said, “is that we often couch it like, ‘Oh, the women who are incarcerated can’t live like that! Therefore we have to help them and get them a newer place.’” Comerford and the women who are incarcerated think we should change our focus. She says, “The women who are incarcerated are like, ‘Uh, get me out of here. I don’t need to be here. Don’t make it a ‘nicer place’ for me to be away from my family. That doesn’t matter. I’m away from my family. My life is stopped.’”

Spurred by these construction plans, Families for Justice as Healing, a Boston-based nonprofit centered around formerly and currently incarcerated women and their family members, approached Comerford, and working together, they proposed Bill S.2030, “An Act establishing a jail and prison construction moratorium.” As the name suggests, the bill would prevent the building of any new jails or prisons within Massachusetts with an expiration of five years.

Comerford presented the bill during the 2021-2022 session. It was approved by both the House of Representatives and the Senate but was vetoed by then-Governor Charlie Baker. His stated opposition was in support of the sheriff’s office’s concerns that the act would disallow maintenance and repair of already existing buildings. While the bill was not intended to prevent these actions, it is being revised during the 2022-2023 session to explicitly state so.

There is little other opposition, according to Comerford. “The bill has been around now, and when bills are around for a number of years, and if you’re doing your job, the opposition decreases because you’ve done enough education around the bill.”

PEOPLE TALKING: CHANGING NARRATIVES

Katie Talbot was “pretty aggravated and pissed off and angry” after her first incarceration. She recalled, “I had always been someone who thought that the system was blind and if someone was hemmed up, they did something to get hemmed up, and people who had the same crime did the same amount of time.” Having gone through the system, she realized that as a white woman, she “benefitted,” and was outraged by the injustice.

This was in 2010 or 2011. Around the same time, Talbot learned about a community organization called Neighbor to Neighbor doing work in prison reform. She got involved, and now, she’s the lead organizer for them, working in Springfield and Holyoke.

“I think we’re not gonna get anywhere until we change that stuff. It’s changing, but there’s still this sense of ‘not me, not my family’ — that the people who go to jail are bad people.”

Katie Talbot, Neighbor to Neighbor

One major component of their work is to discuss the “narrative of who gets incarcerated and why people get incarcerated and really what life is like because of incarceration,” Talbot said of the work at Neighbor to Neighbor. “I think we’re not gonna get anywhere until we change that stuff. It’s changing, but there’s still this sense of ‘not me, not my family’ — that the people who go to jail are bad people.”

Challenging this sentiment, a nonprofit called We Are All Criminals highlights the statistics: “One in four people has a criminal record; four in four have a criminal history.” Their website features dozens of stories from graduate students, teachers, legal and medical professionals, public safety officers, and first responders: criminals who have smuggled drugs, drunk from open containers, and driven recklessly and while intoxicated.

The testimonials describe how they hadn’t been caught or had been reprimanded or had paid fines and had gone to counseling but ultimately having no criminal record and therefore no lasting repercussions. Many of these criminals also reflect on the roles their race, economic status, and other life situations likely played in these outcomes.

One in four people has a criminal record; four in four have a criminal history.

We are all criminals

Neighbor to Neighbor’s works along similar lines, creating dialogue around incarceration and the circumstances leading up to it. “I think there needs to be a level of humanity that’s added to it,” Talbot said. Part of this is “really leaning into conversations that are like, ‘You’re telling me you’ve never sped?’ Just acknowledging that the law doesn’t always line up with morality and the changing of society.”

Comerford and Families for Justice as Healing hope that, on the way to changing policy, their bill will also encourage conversations to challenge the current narratives and focuses of the system.

“Can you imagine what the world would look like in the Commonwealth [of Massachusetts],” Comerford asked, “if there wasn’t a constant conversation about whether we need a new facility? What if we didn’t even have this conversation?”

Instead, Comerford invites a couple of new discussions. For one, she suggests exploring and addressing the root causes of incarceration like “lack of access to education or childcare or transportation,” particularly for incarcerated women.

Talbot echoed these factors when discussing “real safety”: one of the tenets of the criminal justice system. She named “access to good quality housing, clean water and fresh air and good education and access to healthcare, community support and opportunity for engagement in whatever sphere that looks like. Jobs that make people feel purposeful and spaces that make people feel connected” as starting points.

Comerford also hopes to turn attention to the importance of creating different, more effective paths for those who do commit crimes. “We understand that prison as a social mechanism is not the most effective way to deal with those root causes of incarceration,” she said, “so why don’t we try to go to programs that are more effective and happen to be cheaper?”

To make these changes happen, Talbot points to policies that will redistribute resources, like participatory budgeting. Participatory budgeting would allow voters to give input on municipal spending, which is currently only decided by the mayor with feedback from city council. “Everybody has a budget,” she reasons. “Even if you have ten dollars, you still figure out how to budget it. You align how you spend your money with your values.”

Massachusetts recently approved funding for MassReconnect, a scholarship program that covers all tuition, fees, books and supplies for community college students 25 years and older without a postsecondary degree. In the 2024 fiscal year, this program costs Massachusetts $20 million. The often-quoted sticker price for the new prison is $50 million dollars.

Comerford, in addition to thinking that the sticker price is a lowball, points out that the costs wouldn’t stop there. “We’re gonna want to fill that facility,” she said, which then requires additional funding for hiring staff and contracts for cleaning and food. “It’s never ending.”

…AND MAKING CONNECTIONS: MEETING (AS) PEOPLE

A trial case is to triaging in the emergency room as an appeal case is to performing an autopsy, Molly Ryan Strehorn described. In a trial case, “People need help immediately. People have been sleeping in their bed or somewhere that they chose, and now they’re incarcerated.” The time between living as they chose and being “in a cage” is short, which can elicit a lot of different reactions from clients.

In contrast, appeals clients have sometimes been incarcerated for years, and Ryan Strehorn has to piece together their history. Time has also taken its toll by the time she begins her work. “I have one client who’s been incarcerated for decades, and they’re much more emotionally muted,” Ryan Strehorn described. “They’ve gotten used to the sound of the doors clanking closed, the look of prison bars, not wearing their own clothes, not choosing their own food.” Despite the difference in condition and sense of urgency, the underlying humanity remains.

“I’ve been in prison and had full-on belly laughs with people,” Ryan Strehorn recalled, “and it’s not unexpected because we’re all still human, even in our worst circumstances. Even during a sentence for something that’s horrible. I’ve met some people who I really thought, ‘My God, your family must miss you every day.’”

For years, Jarvis Jay Masters was on death row for years in San Quentin State Prison. The prison has since vacated their death row, but Masters remains incarcerated. There has been a campaign, backed by Oprah Winfrey, to free him, and Ellen Kaplan said, “He’s the one person I really fully, a hundred percent believe is innocent. And I don’t care, but I do believe that.”

We’re all still human, even in our worst circumstances.

Molly Ryan Strehorn, Attorney

She began corresponding with Masters around the time her father passed away. “Jarvis was more loving, more caring, more wise,” she said, “he just offered so much, which, on some level of me, surprised [me because he was] a man who spent his life from foster care into prison, into life in prison. And I hated that I was surprised, but I was.”

Unless directly in contact with incarcerated populations, such as through work, as in Ryan Strehorn’s case, specific personal interest, as with Kaplan, or due to a personal connection, most people will not interact with or pay mind to those who are incarcerated. There are, however, a few programs intent on changing that.

There’s a “Prison Exchange Program” out of Temple University in Philadelphia called Inside-Out, which trains higher education instructors to join their classes with students in carceral facilities. Kaplan received said training, and says, “I taught a class that was probably the best class I’ve ever taught, not because of how brilliant I was, but because [the experience of] teaching was amazing.”

Kaplan’s course was about women and violence, which she ironically titled “Weaker Vessels.” The class discussed “concentric circles of violence, all the way from inner — how we do violence to ourselves, to our family, our peer groups, our neighborhoods — onto the educational system, to the larger systems ultimately leading to the carceral system itself.” The class consisted of about 14 or 15 students from Smith College, who had class meetings on campus and also weekly meetings “inside” with the students in the medium security prison in Chicopee.

Kaplan attributes the same type of revelation that she experienced with Jarvis Jay Masters to what made her later work with students so powerful.

“First, there’s this barrier. [With my Smith students,] there was kind of an, ‘Oh, you’ve suffered so much,’ which is just not a way to approach people. It sucks. And on the other hand, many of the incarcerated young women put up an ‘I don’t care’ kind of an armor. I mean, both sides were ridiculous.” Turning the focus on “creative projects and honest discussion” allowed the students to see past the “barrier.”

We don’t know into the hearts of other people. All we can do is stay open and listen.

Ellen Kaplan, Emerita Professor

During one of their discussions, Kaplan remembers a student saying, “‘My father taught me: Somebody hits me? Hit back 50 times harder.’ And I’m like, I get it,” Kaplan said. “I don’t agree, but my life circumstances are different. I’m not here to tell you how to think. I am here to ask you to think about it.”

This intentional thoughtfulness and consideration for how we are and why we are that way is the key to “overcoming that really false distinction” between people in different places. “On a basic level, our experiences may differ,” Kaplan says, “but we don’t know into the hearts of other people. All we can do is stay open and listen.”

Lynne Sullivan of the Petey Greene Program has seen similar developments and connections in the tutors she coordinates. She’s seen former volunteers become lawyers and teachers, inspired by their work tutoring incarcerated folks.

“And what really gets me the most,” she said, “is when I have a young student, and they say, ‘I never really looked at [incarcerated people] that way before. But they’re just like me. Society portrays them as this and that. But, oh my God, they’re human. They’re just like me.’”

To Sullivan, this epiphany is the “the best thing” she can hear. “Because when you start looking at someone as a human being, you’re less apt to treat them as poorly as you do.”

And what really gets me the most is when I have a young student, and they say, ‘I never really looked at [incarcerated people] that way before. But they’re just like me. Society portrays them as this and that. But, oh my God, they’re human. They’re just like me.’”

Lynne Sullivan, The Petey Greene Program

RESTORING JUSTICE — AND HUMANITY

Kaplan and Sullivan have found and facilitated a number of ways for those to affect those in the criminal justice system from the outside-in. Becky Michaels is working fully on the inside.

Michaels is Assistant District Attorney and Director of Community Prosecution Projects in the Northwestern District of Massachusetts, which is composed of Hampshire and Franklin Counties and the town of Athol. Under her direction, Hampshire County launched a restorative justice program for adults in January 2021.

The restorative justice program is an alternative to typical prosecution. The defendant, now deemed “responsible party,” sits “in circle” with a facilitator and, often, the victim to examine the harm caused. Together, the group determines any future actions the responsible party might take to rectify the situation.

“For a restorative justice program to have integrity, it has to be separate from the criminal justice system and, really, separate from any system,” Michaels explained. “Ideally, it arose from the community because the purpose of restorative justice is to repair the harm caused to the community.” With this in mind, Michaels sought out a community partner and found Communities for Restorative Justice (C4RJ).

The purpose of restorative justice is to repair the harm caused to the community.

Becky Michaels, ADA

C4RJ is a nonprofit based in Boston that also collaborates with Suffolk and Middlesex DAs offices’ juvenile work. For Michaels, part of C4RJ’s draw was that they partner with police departments directly. As a result, if the police departments determine a case’s eligibility quickly enough, the case will never appear in the DA’s office or, therefore, the responsible party’s criminal record.

While specific restorative justice practices vary, in Hampshire County, the work in circle is entirely confidential, so while the responsible party admits to the harm they caused, this is different from admitting to a crime. (Successful prosecution of a crime requires the verification that various conditions composing a crime were all satisfied.)

Throughout the process, C4RJ volunteers can refer the case back to the DA’s office if they feel that the responsible party isn’t engaging, but otherwise the DA’s office is uninvolved. After sitting in circle — a process that often takes six to nine months — the case is resolved.

A Vox article describes some of the promises of restorative justice as practiced broadly in the US. Some research, including one meta-analysis (whose authors are hesitant to claim broad reliability due to some limitations of the studies) and one experimental study, suggest that restorative justice processes can reduce recidivism rates. The article also points to a study suggesting high rates of satisfaction from victims: 91% said they would participate again and recommend the process to a friend.

However, restorative justice doesn’t claim to be a panacea for all wrongdoings. In fact, the scope of cases for which it’s an option is quite limited for a number of factors.

The Vox article also notes some limitations, such as expectations of forgiveness, especially in close, fraught relationships. The DA’s office and C4RJ are mindful of this, excluding cases of domestic violence or with a victim who’s disabled or elderly could connote “issues of power and control.”

Other cases that they may deem inappropriate for the restorative justice program could include ones that don’t have a specific victim, e.g. driving under the influence, or ones involving someone who “poses a danger to the community or to a particular person,” Michaels explained.

Additionally, cases eligible for the restorative justice program can’t involve substance abuse. Instead, they’ll because these cases will be diverted to their Drug Diversion and Treatment Program, which is directed by Maria Sotolongo.

The Drug Diversion and Treatment program began in 2016 and can receive any person whose charges involve substance abuse. “Whatever the crime is — whether it’s shoplifting, possession, breaking, entering — whatever it is, [Sotolongo] ends up diverting, referring them to one of the local community providers of treatment,” said Michaels. While in the program, the DA’s office gets a monthly update but takes no action. As long as the person is in compliance with the program, they continue until achieving six consecutive months in compliance, at which point their case is dismissed.

There were two equal parties in this: not equal in terms of fault, but we’re two people who each bring to this moment in time our own stories and our own complexities.

Becky Michaels, ADA

The restorative justice program is currently somewhat limited by both personpower (the program launched with 10 volunteers, and circles are time- and energy-intensive) and case eligibility. As of October 2023, Michaels said the program diverted about 80 cases since launching while prosecuting about 5,000 per year.

However, the realm of possibilities for restorative justice cases is growing. “As we’re getting more comfortable with seeing the results of it, and as defense attorneys are getting more comfortable with it, we’re starting to expand the kinds of cases we can imagine sending.”

Restorative justice doesn’t match the image of “justice” that most people have in their heads. “I think people who have not been through the system at all have a vision of what it means to have justice be done,” said Michaels, mentioning examples of incarceration and probation. “And I don’t think that either of those two outcomes is necessarily helpful in a lot of cases for prevention, rehabilitation, or making a victim feel whole.”

Restorative justice might sound like an easy way out, but Michaels says, “It’s much harder to sit in a room across from a person you’ve harmed and have to look them in the eye and hear from them than to be checking into probation every now and then for a year.” It also allows greater mutual understanding: “There were two equal parties in this: not equal in terms of fault, but we’re two people who each bring to this moment in time our own stories and our own complexities.”

QUICK REMINDER, BEFORE YOU GO

“We forgot that people don’t just want to go to jail,” Lynne Sullivan mused. “They weren’t just born to go to prison. They didn’t wake up and say, ‘I want to go to prison. I’m going to go do this crime so I can go to prison.’ No, there is an underlying pathway, whether it’s our system structures, personal challenges, economic, racial — there’s all a foundation that led into that pathway.”