Self-Portrait with Easel (1930)

Sher-Gil painted nineteen self-portraits while she was in Paris, most likely as a way of exploring and expressing her identity as well as honing her artistic skill. For example, “Self-Portrait with Easel” seems to focus on Sher-Gil’s identity as a painter. Her somber expression, when compared with that of other self portraits, speaks to her serious attitude about her work; it is clear that art is not merely a frivolous pastime, as was often assumed of female art at this time, and evokes the melancholy undertones found in much of her later work. The use of the color red in her garment and her lips, suggesting passion and sensuality, is also a recurring element throughout her artistic career. The force with which Sher-Gil draws attention to her dark brow and strong features in this painting seems a statement about both her femininity and ethnic identity; this choice may be interpreted as Sher-Gil struggling to find and assert her place in the art world, as can be seen in other paintings from this time such as “Self-Portrait as Tahitian.”

Professional Model (1933)

During her time in Paris, Sher-Gil often used figures from the busy nightlife of the city as subjects in her paintings, portraying both the allure of the Paris lifestyle and its sordid underbelly. Both are showcased in this work. The painting’s title suggests a symbol of glamour and sophistication; yet, the woman in the painting is hunched in shadow. Her pale skin, which in another context might be seen as an aspect of beauty, appears sickly against the dark background, and her nude body, in its limp, wilted position, suggests vulnerability rather than any sort of sexual appeal. The painting seems to suggest that the flashy appearance of such fashionable figures in the social world of Paris conceals dissatisfaction. This painting also foreshadows Sher-Gil’s later attempts to separate the female nude from catering to the male sexual gaze by portraying it in non-sexual scenes, where the subject is turned away from the viewer.

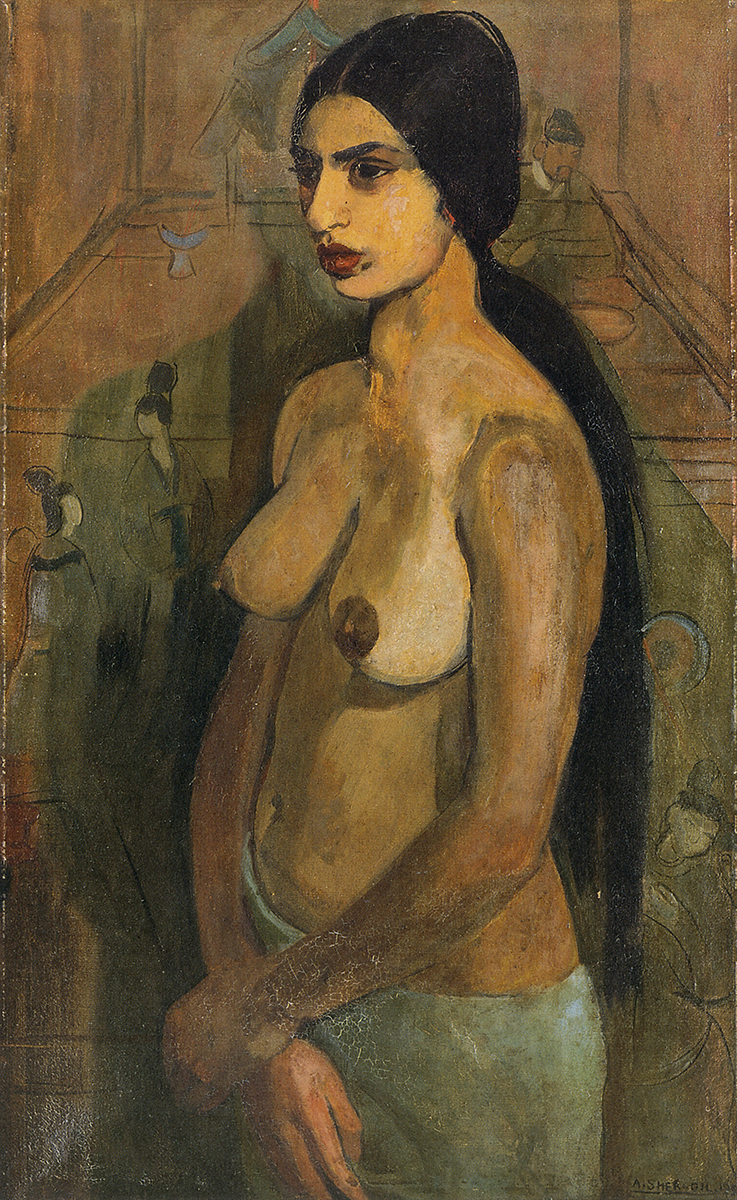

Self-Portrait as Tahitian (1934)

Sher-Gil’s Self-Portrait as Tahitian, one of several self portraits that Sher-Gil completed while in Paris, explores her struggles to come to terms with her mixed racial identity and femininity within the art world of the Modernist period, which was conceived as essentially white and male. Her decision to paint herself as one of Paul Gauguin’s “Tahitian” women reflects the conflict between the influence she drew from his technique and her feelings about his artistic treatment of the non-white woman as an uncivilized, sexually available and submissive object. Thus, while the subject is partially nude, her body and gaze are turned away from the viewer, not in a state of display. The shadow in the background, who mimics a common figure in some of Gauguin’s paintings, represents the male gaze, both in the sense of male artists objectifying the non-western female and the critical eye of the male-dominated art world upon Sher-Gil and her work. Sher-Gil’s reappropriation of modernist technique and tradition for her own purposes connects with her later works, in which she combines Western styles with Indian subjects and artistic tradition to create uniquely Indian works of modernism.

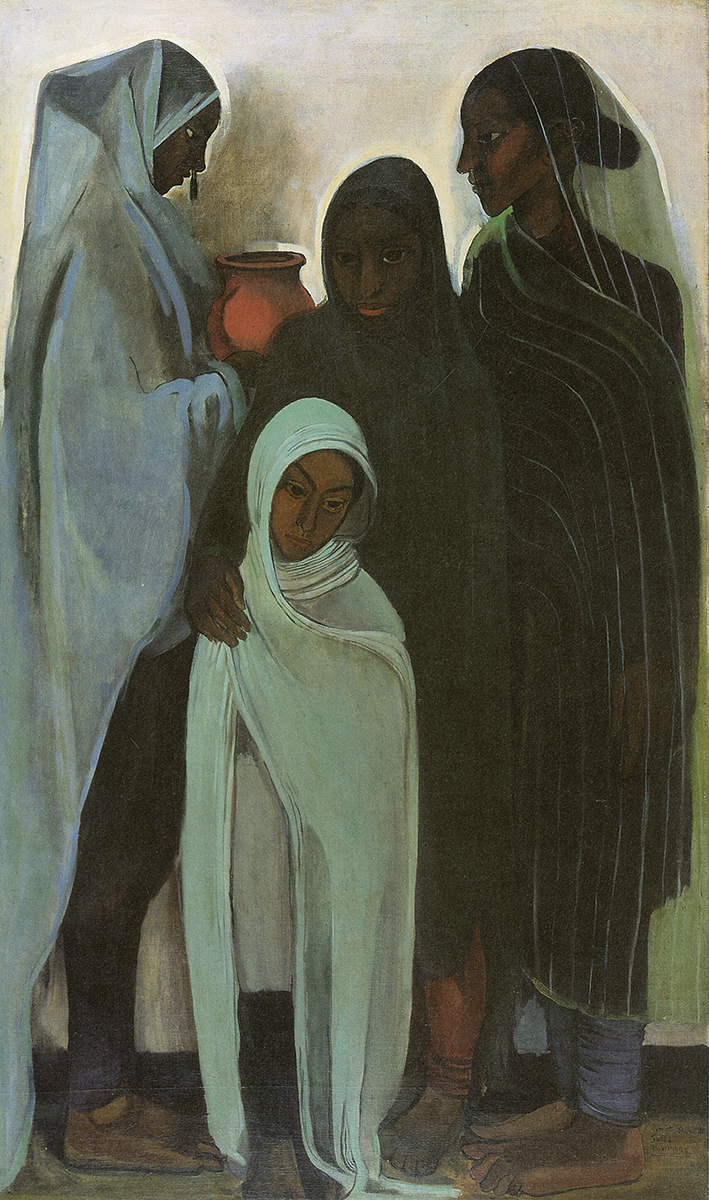

Hill Men (1935) and Hill Women (1935)

Hill Men and Hill Women are reflective of Sher-Gil’s goal to depict the the lives of the rural Indian poor. Their more muted colors (relative to her other works) and the somber expressions of the figures in the paintings underline the melancholy tones that are present in many of Sher-Gil’s portraits, possibly as a response to the idealized views of western modernists about lives in “exotic” rural communities. The figures in these paintings are also more stylized and two-dimensional than those in her Paris works, suggesting a closer attention paid to form, possibly in order to avoid outright sentimentalism or the “cheap emotional appeal” that Sher-Gil felt resulted from “the picture that tells a story.” (Ananth 20) The stark color contrasts are also important to note, particularly in Hill Women, between the light and dark clothing and skin tones.

Brahmacharis (1937)

Brahmacharis, one of Sher-Gil’s better known works, was painted after her tour of India. Inspired by those people she saw on her travels through rural villages of South India, the painting is often referred to as being part of her “south Indian trilogy” along with “Bride’s Toilet” and “South Indian Villagers Going to Market.” The former two paintings also show the considerable influence of the Ajanta frescoes; for example, the positions of the men in Brahmacharis echo the ‘tensed arm and floating hand’ found in the Ananta figures. (Ananth 22) The red tones in the background suggest, in this work, a kind of spiritual passion and energy. The figures are more stylized and less detailed than those of her earlier works; more of the painting’s atmosphere comes from its strong lines and striking use of color than from the expressions of the figures themselves. Sher-Gil noted about this painting that she varied the skin tones of the figures and the subtle tones of their white clothes in such a way that they achieve a “certain overall uniformity” but that the different tones “do not disturb the calm of the picture.”

Bride's Toilet (1937)

“Bride’s Toilet”, inspired by Sher-Gil’s experiences in South India and the frescoes at Ajanta, is part of the “south Indian trilogy” which consists of “Bride’s Toilet”, “Brahmacharis,” and “South Indian Villagers Going to Market.” Like “Brahmacharis,” Bride’s Toilet displays its roots within the Ajanta frescoes through its use of the raised hand and open palm, a common feature of figures in the Ajanta cave paintings. (Ananth 22) The arrangement of the fair-skinned bride and her attendants with darker skin tones also reflect similar arrangements in the Ajanta frescoes (Ananth 22) and also may be a nod to class and racial relations within India. It is interesting to note that one of the attendants, rather than the bride, is placed most in the foreground of the painting. “Bride’s Toilet” contains more variations of color than its companion “Brahmacharis.” It is full of different tones of yellow, green, and brown as well as a deep red found on the bride’s clothing and hands that contrasts strikingly with her pale skin, possibly used here within the context of a wedding as a symbol of sensuality and passion.

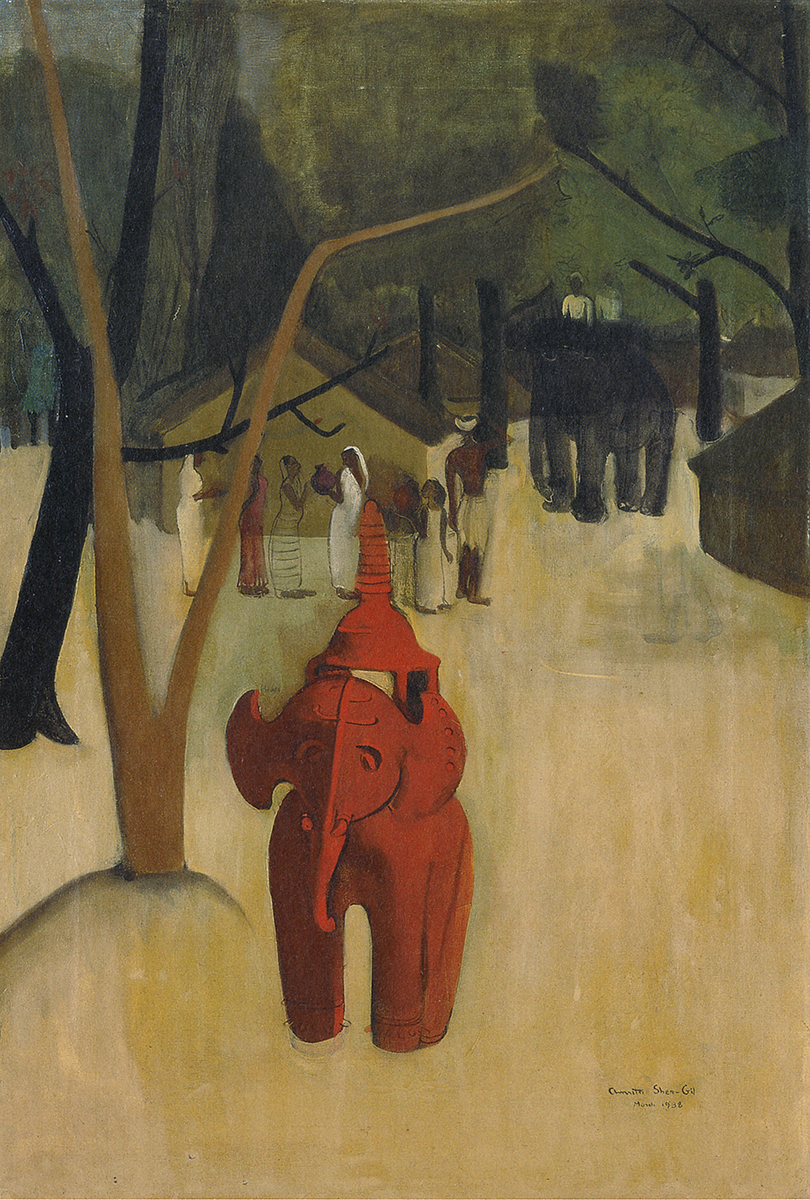

Red Clay Elephant (1938)

Sher-Gil’s “Red Clay Elephant” displays the growing influence that the Mughal miniature portraits had on Sher-Gil; as she grew more interested in them, her work became smaller in scale, more detached from the emotion of the subjects, and more stylized in a type of “flat relief.” (Sundaram v. 2, 483) She describes her growing preference for these miniatures and their “primitive outlook and vivid sense of color.” (Sundaram v. 2, 480) She also began to expand the scope of her paintings’ subject matter. “Red Clay Elephant” departs from the realism of much of her paintings in depicting the lives of the Indian poor. The painting achieves a vibrant color contrast with the yellow foreground, red clay, and dark background, and it follows the trajectory of her work with its favor of strong lines and colors. Sher-Gil also became more interested in painting animal subjects at this time, as can be seen in other paintings such as “Bathing Elephants” and her unfinished final work.

Two Girls (1939)

“Two Girls,” while it is a large work, also displays Sher-Gil’s growing attachment to the style of Mughal miniature paintings. It is much more monochromatic and less detailed than her earlier works, and the figures in the painting are defined much more by line and positioning than by any sort of facial expression. They are heavily stylized and display the sort of “flat relief” that Sher-Gil sought from her work in this period. The contrast between the skin tones of the two girls could be interpreted as a nod to Sher-Gil’s mixed heritage, and the painting’s subject matter of feminine intimacy is certainly within Sher-Gil’s pattern of depicting the lives of Indian women in their own right. The intimacy of the two women and their positioning has been widely thought to be an expression of Sher-Gil’s bisexual tendencies and speculated affairs with women. In the context of the painting, this idea might also be interpreted as a liberation of female sexuality from the male gaze and an exploration of sexual desire and sensuality in Indian females, a topic often evoked in Sher-Gil’s work.

Woman Resting on Charpoy (1940)

As in many of Sher-Gil’s later works, the figure in “Woman Resting on Charpoy” is not isolated from her environment, but situated within the surroundings of her home as part of Sher-Gil’s approach to depicting Indian life. Her later paintings such as this one also display a lack of outright expression from the figures themselves, leading to increased ambiguity and relying on color and form to express the paintings’ meaning. The woman’s relaxed, pose and red clothing suggest sensuality and sexual desire; “Woman Resting on Charpoy,” thus, is part of Sher-Gil’s attempt to communicate the sensuality within Indian women and how this sensuality expresses itself within the boundaries of society. This painting also points to female sexuality within Indian women as independent agency, rather than passive availability for male desire. “Woman Resting on Charpoy” in this way contributes to Sher-Gil’s goal of displaying through her art the inner life of Indian women.

Sher-Gil's last painting (Unfinished; 1941)

While Sher-Gil’s final painting is unfinished, we can see the hallmarks her late artistic style in its beginnings. It favors strong lines and color contrasts, containing shapes of bright red as well as very dark colors, perhaps an expression of the depression she experienced towards the end of her life. There are no figures present in the painting, and it displays the clear-cut and simple shapes that marked her later paintings, evidence of the influence the Mughal miniature paintings had on her work. Animals are also present in the foreground; this is common in her later works, as she often traded human figures for elephants, camels, horses, and the cows or bullocks that we can see in this painting. Although it is unfinished, the strong, clear forms and bright red hues of her final painting make it clearly recognizable as Sher-Gil’s and display the culmination of the evolution of her painting style.